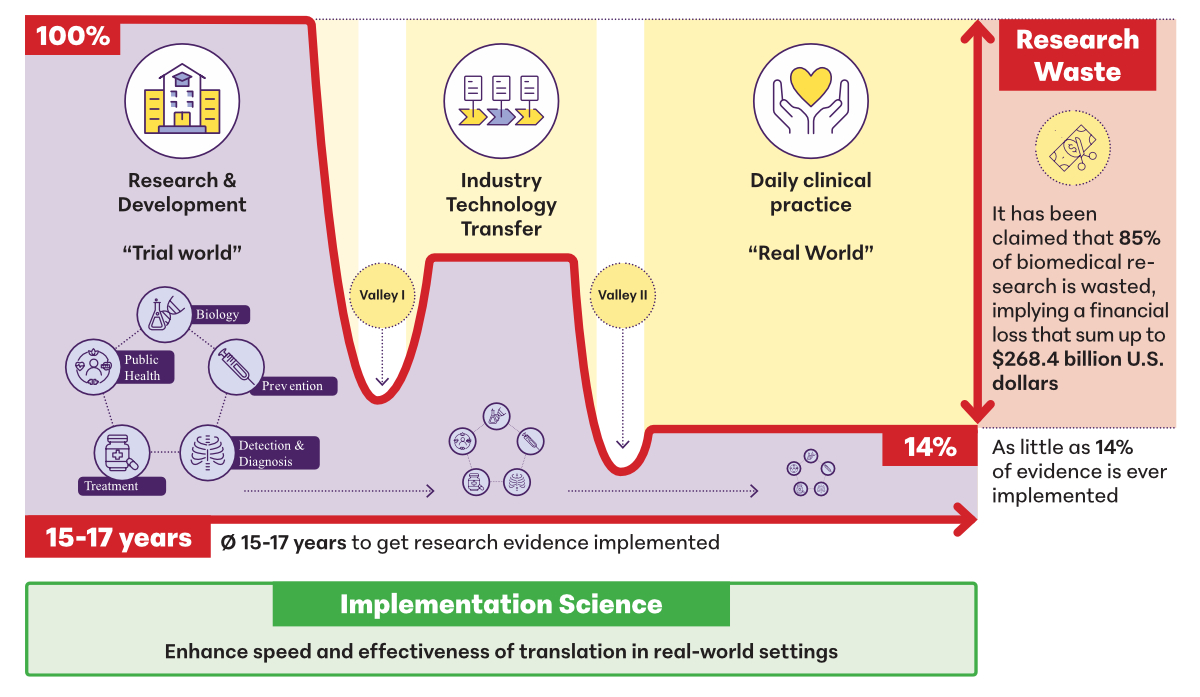

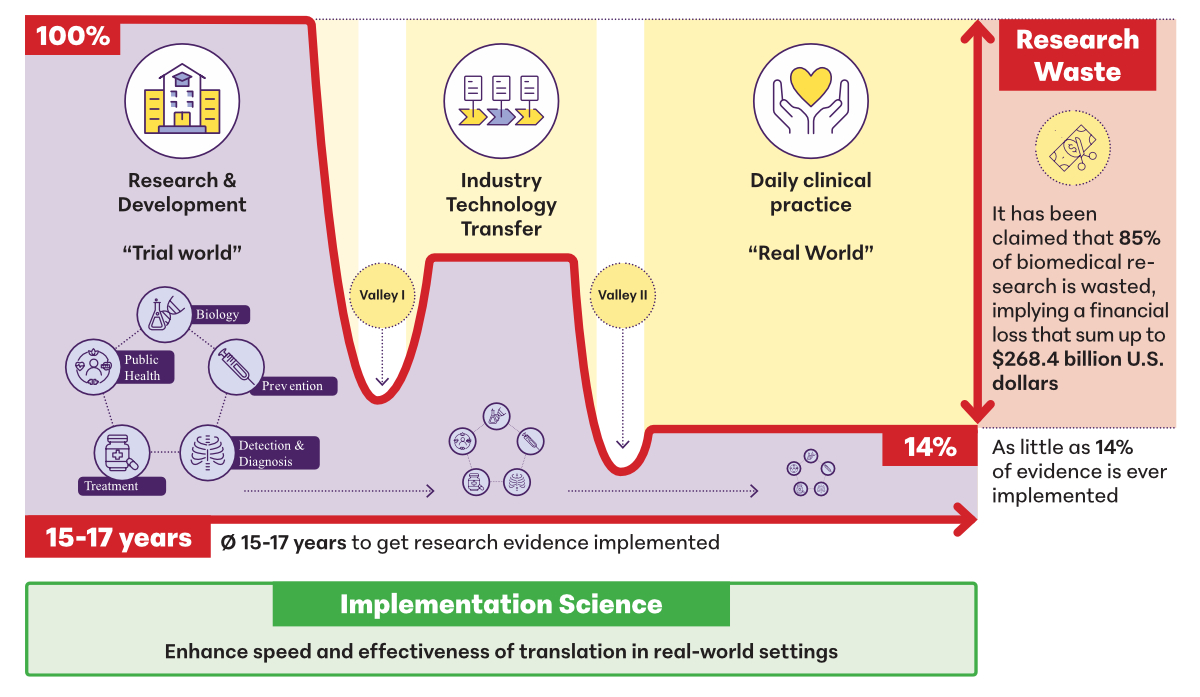

Figure 1Overcoming the Valleys of Death with Implementation Science [2–4].

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4501

Switzerland stands out as an innovative and research-intensive country. For instance, in 2021, the public and private sectors invested CHF 24.6 billion in research and development (R&D) [1]. However, there is a need to increase the societal impact of these investments by enhancing the effectiveness and speed of translating evidence-based practices and innovations into real-world settings and daily clinical practice and public health. Historically, efforts have primarily focused on bench-to-bedside translation. Yet, the full societal impact of innovations unfolds when translational efforts extend across the entire research pipeline from discovery to application within health service delivery.

The final stage of translating evidence-based interventions and innovations into practice in real-world settings remains a particular challenge. The numbers describing these so-called “valleys of death” are staggering [2]. On average, as little as 14% of innovations (such as programmes, practices, pharmaceutical products, procedures and policies) become embedded in routine service delivery, with even lower rates of sustainability. There is a widely cited 17-year lag for the successful implementation of innovations into practice. Progress is slow, as evidenced by a recent publication in cancer research, indicating that the time lag until half of the eligible population accesses the intervention/diagnostics is 14–15 years [3]. In turn, it has been estimated that 85% of investment in biomedical research is wasted (figure 1) [4].

Figure 1Overcoming the Valleys of Death with Implementation Science [2–4].

These challenges underscore the pressing need for Switzerland to place stronger emphasis on improving translation of its substantial R&D investments into practical applications that benefit healthcare and society, ensuring that the country’s innovative potential is fully attained. The example of digital innovations in healthcare, high on the policy agenda of many countries, provides a useful illustration of unrealised potential. Indeed, many digital health transformations fail to be successfully implemented in healthcare delivery. Reasons are multifaceted, including a high number of innovations being developed without adequately considering end-users’ needs and perspectives such as preferences of patients and families, in their development and translation into practice. Additionally, limited attention is given to the contexts in which digital solutions need to be integrated. Interoperability with existing IT systems frequently fails during implementation, and broader system considerations (e.g. legislation and the General Data Protection Regulation) are not addressed early enough, leading to failed implementation [5].

Furthermore, to meet the need for better and faster implementation of evidence-based approaches and strategies into practice, deimplementation of low-value interventions provides a major opportunity to render healthcare systems more efficient and effective. Not only can some interventions be harmful to patients, but low-value care is also an important source of wasted resources. For example, between US$ 12.8 billion and US$ 28.6 billion could be saved annually in the United States alone if measures were taken to reduce overtreatment and low-value care [6]. Specific opportunities for deimplementation of low-value care have been highlighted by Switzerland’s Smarter Medicine initiative, such as not prescribing antibiotics for infections or inflammation of the throat or larynx, given that they are usually caused by viruses.

Implementation science, defined as “the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice, and, hence, to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services and care” [7], is an approach that places the translation of innovations into daily clinical practice and real-world settings at its core. This approach can also guide the deimplementation of low-value or harmful practices. Implementation science builds upon clinical and epidemiological research methods, while adding elements that highlight the essential inclusion of broad stakeholder perspectives and a thorough contextual analysis to inform intervention development and the choice of implementation strategies [2].

Implementation science emphasises evaluation not only of effectiveness outcomes but also sheds light on implementation processes and outcomes such as feasibility, acceptability and fidelity. It is transdisciplinary and embraces collaboration between clinical, public health, social science and clinical settings. By doing so, the likelihood of successful implementation is enhanced, and a much greater understanding is reached not only about whether an intervention works in real-world settings (typically the focus of pragmatic trials) but also why and how it works (or doesn’t) and for whom [2].

We argue that implementation science should be regarded as an essential building block in research infrastructures to tackle the “valleys of death”, reduce research waste, and accelerate and increase the efficiency of healthcare services. The value of implementation science has been highlighted by leading scientific journals such as JAMA, The New England Journal of Medicine and Science [8]. Internationally and in Switzerland, implementation science has gained traction within university settings as well as in the pharmaceutical industry in efforts to make research infrastructures more performant in view of real-world translation and to generate more societal value and revenue.

Enriching Swiss clinical and public health research infrastructures with implementation science could further boost Switzerland’s R&D ecosystem to new heights [9]. In the past decade, major investments have been made in creating clinical trial units, cohort studies and biobanks, and other types of research infrastructures such as the Swiss Personalised Health Network (SPHN) (https://sphn.ch/). However, innovations stemming from these investments need to be integrated into daily practice. Implementation science, as an essential part of a performant research infrastructure, can facilitate this integration.

It is noteworthy that specific funding initiatives focusing on translation into practice at the end of the R&D pipeline have supported implementation science projects. For example, the National Research Programme Smarter Health Care of the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) has now been continued as an initiative under the same name, Smarter Health Care network (https://www.nfp74.ch/en/pMvbz2PaCnVAzAw2/news/smarter-health-care-the-dialogue-is-moving-forward). The SNSF is currently supporting Implementation Networks to ensure findings of previous National Research Programmes (NRPs) are translated into changes in practice through strengthened interactions between researchers and non-scientific actors [10]. Additionally, the National Quality Commission of the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) funds specific projects that apply implementation science to increase patient safety and quality in Switzerland, highlighting investments bridging the gap between research findings and practical applications in healthcare settings.

The creation of the Swiss Implementation Science Network (IMPACT) (https://impact-dph.unibas.ch/) in 2019 further exemplifies the increased focus on implementation science as an essential part of the Swiss research infrastructure to overcome the knowledge-practice gap. Now consisting of 11 partners spanning universities and healthcare organisations, IMPACT invites all interested parties to contribute to the development of implementation science infrastructures in Switzerland across universities, clinical environments and pharmaceutical/biotech companies. IMPACT is an open network for all individuals or organisations committed to implementation science and is driven by five main goals: (1) showcasing implementation science projects in healthcare and health-related sciences, especially those conducted by researchers and institutions hosted in Switzerland; (2) providing networking opportunities for implementation science researchers and other interested stakeholders, including implementation practitioners and end-users in Switzerland; (3) promoting skills and knowledge-building in implementation science and highlighting quality educational opportunities; (4) leveraging funding opportunities for implementation science in Switzerland and for the IMPACT network itself; and (5) advancing implementation science methods for rigorous research and practice.

IMPACT operationalises these goals through various instruments. Educational initiatives include an annual conference, quarterly webinars, a dedicated YouTube channel (https://impact-dph.unibas.ch/resources/) and newsfeeds of national and international developments in implementation science. Recently, a repository for implementation science projects conducted by Swiss researchers was launched at https://impact-dph.unibas.ch/repository/. IMPACT also endorses projects that align with its mission.

Given the considerable research inefficiencies and delays in translating innovations into real-world applications, balancing investment in R&D with a stronger focus on translation in healthcare delivery is imperative. By ensuring that implementation science is well-positioned and integrated within Swiss research infrastructures, Switzerland can further strengthen its innovative capacity, accelerate the translation of research into practice and ensure that scientific advancements are effectively integrated into real-world settings to improve healthcare outcomes and benefit society as a whole. Through initiatives like IMPACT and targeted funding programmes, Switzerland can ensure that its groundbreaking discoveries not only reach patients and healthcare systems more efficiently but also deliver meaningful societal impact.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. – SMDG received consulting fees from Novartis and honoraria for educational sessions from Novartis and Roche Diagnostics. – TB received grants from the Swiss Nursing Science Foundation (PI), participated on the scientific board of the Swiss Nursing Science Foundation and is a board member of the Swiss Implementation Network & European Implementation Collaborative. – KW received grants from health promotion Switzerland for evaluating various suicide prevention projects as well as the prevention of psychosocial burden of disease in a hospital setting in Switzerland. He holds further research grants from Réseau de l’Arc and the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health for assessing the implementation and outcome of an integrated care network in Switzerland as well as the European Commission under Horizon 2020. For the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation and the German “Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau”, he holds a consultant role. For the German “Forschungsgemeinschaft” and the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership under Horizon Europe, he regularly acts as an external reviewer. He is a board member of the Swiss School of Public Health and “Public Health Fachrat Schweiz”.

1. Swiss Federal Authorities [Internet]. Federal Statistical Office: Almost CHF 25 billion dedicated to research in Switzerland in 2021; 2023 [cited 2025 Mar 13]. Available from https://www.bfs.admin.ch/asset/en/24368697

2. De Geest S, Zúñiga F, Brunkert T, Deschodt M, Zullig LL, Wyss K, et al. Powering Swiss health care for the future: implementation science to bridge “the valley of death”. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020 Sep;150(3738):w20323.

3. Khan S, Chambers D, Neta G. Revisiting time to translation: implementation of evidence-based practices (EBPs) in cancer control. Cancer Causes Control. 2021 Mar;32(3):221–30.

4. Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet. 2009 Jul;374(9683):86–9.

5. Mumtaz H, Riaz MH, Wajid H, Saqib M, Zeeshan MH, Khan SE, et al. Current challenges and potential solutions to the use of digital health technologies in evidence generation: a narrative review. Front Digit Health. 2023 Sep;5:1203945.

6. Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. Waste in the US Health Care System: Estimated Costs and Potential for Savings. JAMA. 2019 Oct;322(15):1501–9.

7. Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Welcome to Implementation Science. Implement Sci. 2006 Feb;1(1):1.

8. Proctor EK, Geng E. A new lane for science. Science. 2021 Nov;374(6568):659–659.

9. State Secretariat for Education. Research and Innovation (SERI) [Internet]. Swiss Roadmap for Research Infrastructures; 2023 [cited 2025 Jul 10]. Available from: https://backend.sbfi.admin.ch/fileservice/sdweb-docs-prod-sbfitestch-files/files/2025/05/08/9d0d7110-f2ce-4ad4-968a-cf3745f7f511.pdf

10. Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) [Internet]. Implementation Networks: first four projects selected; 2023 [cited 2025 Mar 13]. Available from: https://www.snf.ch/en/lVTVSZHVZNuY1VwP/news/implementation-networks-first-four-projects-selected