Figure 1Participant flow diagram.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4453

Preterm birth (PTB) remains a leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality, often resulting in long-term health issues for the child, such as developmental and neurological disorders [1]. In approximately 70% of cases, preterm birth is driven by spontaneous preterm labour (PTL) or premature preterm rupture of membranes (PPROM). While both conditions lead to preterm birth, they differ substantially in aetiology, clinical presentation and management strategies. Preterm labour is typically characterised by regular uterine contractions with cervical change and intact membranes, whereas premature preterm rupture of membranes involves rupture of foetal membranes before labour onset [2, 3]. Tocolysis, which aims to inhibit preterm contractions, is a key intervention primarily used in the setting of preterm labour to delay delivery and allow for antenatal corticosteroid treatment (ACS) and in-utero transfer to a perinatal centre. Pharmacologically, uterine relaxation is achieved through calcium-channel blockade, β₂-adrenergic receptor stimulation or oxytocin receptor inhibition. These agents have been shown to be more effective than placebo in delaying delivery for up to 48 hours [4, 5]. In contrast, tocolysis in premature preterm rupture of membranes is more controversial, as inhibition of these contractility pathways in the absence of contractions is mechanistically questionable and the benefits must be weighed against the increased risk of infection due to prolonged membrane rupture.

Despite the advantages of tocolysis, its effectiveness remains debated, particularly as it does not significantly lower rates of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome or death [4]. According to the most recent Guideline on Prevention and Therapy of Preterm Birth of the German, Austrian and Swiss Societies of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (German Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics [DGGG], Austrian Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics [OEGGG] and Swiss Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics [SGGG], respectively), the primary objective of tocolysis is to prevent birth within the next 48 hours, which enables administration of antenatal corticosteroid treatment and maternal transfer [6]. In Switzerland, the recommendations are in line with these international guidelines. Maintenance tocolysis beyond 48 hours is not recommended. Tocolysis is indicated before 34+0 weeks of gestation in the presence of uterine contractions and cervical changes, while its use beyond this threshold is discouraged in uncomplicated pregnancies. In premature preterm rupture of membranes cases, tocolytics should be used only selectively and typically for a short period during antenatal corticosteroid treatment administration to prevent contractions. First-line agents include calcium-channel blockers and oxytocin receptor antagonists, while beta-sympathomimetics are considered second-line due to their adverse effect profile. Antenatal corticosteroid treatment is recommended between 24+0 and 33+6 weeks, with rescue courses reserved for specific clinical indications. International studies have shown that clinical practice often deviates from these evidence-based guidelines [7–13].

The aim of our study was to investigate how tocolysis and antenatal corticosteroid treatment are being handled in Switzerland, the extent to which physicians adhere to current guidelines, and which challenges are faced in clinical practice. We therefore conducted a cross-sectional, anonymous survey among Swiss obstetricians on preterm birth management practices. Modelled after a survey study previously conducted in Germany [8], the current survey was specifically designed to target the Swiss population, while still ensuring comparability of results. Several aspects of the most recent guideline of the German Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Swiss Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics and Austrian Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics – including a special statement reflecting a Swiss-specific clinical perspective — were taken into account.

This study was a national, cross-sectional survey involving obstetricians in Switzerland. The survey was conducted using the online tool SoSci Survey® (program version 3.4.22, Leiner, 2024, Munich, Germany). By installing the software on University Hospital Zurich’s own server, participant responses were stored locally, thereby ensuring compliance with data protection regulations. Data was stored in an anonymised format, and all participants actively and voluntarily agreed to take part in this survey. Primary outcomes assessed adherence to evidence-based guidelines, specifically regarding the duration and timing of tocolysis. These were operationalised by assessing the percentage of respondents who continued tocolytic therapy beyond the recommended 48-hour limit (maintenance tocolysis) and those who reported administering tocolytics beyond 34 weeks of gestation. Secondary outcomes examined variations in practice patterns, including the selection of specific tocolytics, measured by the frequency of reported use of each drug class; management strategies for high-risk pregnancies, assessed by whether physicians adjusted their tocolytic choice based on risk factors; and responses to tocolysis failure, evaluated by the proportion of respondents indicating strategies such as switching agents, discontinuation or combination therapy. Additionally, the survey explored indications, contraindications and objectives of tocolysis in clinical practice, quantified through multiple-response questions.

Given the interprofessional nature of maternity care, a variety of channels were employed to ensure the survey reached physicians in hospitals and in private practices. The questionnaire was distributed to 94 chief physicians via the email distribution list of the Swiss Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics Chief Physicians’ Conference, with a request that it be forwarded to the medical team (residents, senior physicians, heads of department). Additionally, it was sent to 481 practice email addresses of private-practice gynaecologists, which were ascertained via the authors’ personal networks and a clinic internal directory of practices due to the absence of a centralised registry. A follow-up e-mail was sent one month after the initial request for participation in the survey. Additionally, the survey link was included in the newsletter of the Swiss Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, which has an estimated 2880 recipients, and via the Instagram channel of the Young Forum of the Swiss Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, which has approximately 340 followers. Due to the variety of channels through which the questionnaire was distributed, the total number of recipients and the corresponding response rate could only be roughly estimated. The survey period ran from 15 February 2024 to 30 May of the same year. No incentives were provided for participation.

A structured, anonymous self-report questionnaire was designed by the authors based on a previous analogous survey [8, 9] and adapted to address clinical practice in Switzerland (the English version is available as a supplementary file for download at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4453). To ensure representative results and minimise selection bias, both the email invitation and the questionnaire were provided in the three main Swiss languages: German, French and Italian. In designing the questionnaire for the online survey, consideration was given to the fact that potential participants could be employed in a variety of work environments, including hospitals (hospital physicians), private practices (private-practice physicians) and private practices with additional attending duties in an obstetrics department (attending physicians). Consequently, hospital physicians, private-practice physicians and attending physicians received different sets of questions relevant to their specific roles. Furthermore, filter questions were incorporated, whereby subsequent questions were displayed based on prior responses, thus ensuring relevance and clarity across distinct professional contexts. All questions in the online survey were mandatory and had to be answered in order to proceed with, and to complete and submit the questionnaire. This was ensured by programming the questionnaire accordingly. Therefore, there is no missing data. The questions were organised into the following six distinct topic groups, with hospital and attending physicians receiving all questions, while private-practice physicians were asked only those relevant to outpatient management:

A pre-test with five Obstetrics Research employees (Department of Obstetrics, University Hospital Zurich) evaluated the survey’s clarity and relevance, leading to refinements in wording and structure for improved comprehension.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and with Swiss laws and regulations. In compliance with Swiss Federal Law on data protection (Human Research Act, Article 2) and non-clinical trials (Human Research Ordinance, Article 25), no ethics committee approval was required since the data was anonymously collected. This has been confirmed by jurisdictional declaration of the ethics committee of Zurich for previous similar anonymous surveys [14, 15].

The statistical analysis was conducted using IBM® SPSS Statistics software (program version 29.0, Leiner, 2024, Munich, Germany). Microsoft Word® and Excel® (program version 16.91, Microsoft Corporation, 2024, Redmond, WA, USA) were employed for the creation of tables and graphs. Categorical data from single-response questions was summarised using counts and percentages. For multiple-response questions, the total percentage may exceed 100% because it reflects the proportion of respondents selecting each option. This method enables a more nuanced analysis of response patterns, highlighting the frequency and distribution of selected options. Where appropriate, numeric input questions (e.g. gestational age thresholds) were included to gather precise quantitative data. It should be noted that the percentages do not always refer to the total population (n = 319) but to the specific subgroups (hospital physicians, private-practice physicians or attending physicians) mentioned in the text. In the tables, data is presented as n (%). Due to the questionnaire’s programming, incomplete responses could not be submitted and were therefore automatically excluded from analysis. This ensured consistency, as the survey included subgroup-specific branching logic.

A total of 445 physicians started to answer the questionnaire from which 319 physicians (72%) completed the questionnaire and were available for analysis, including 265 specialists and 54 physicians in training (i.e. resident physicians) (table 1; for details on exclusion, see figure 1).

Table 1Distribution of physician roles across practice and hospital settings.

| Physician group | Number of physicians, n (%) | ||

| Practice | Resident physician | 1 (0.3) | |

| Specialist | Attending physician | 50 (15.7) | |

| Non-attending physician | 67 (21.0) | ||

| Hospital | Specialist | Chief physician | 33 (16.4) |

| Head of Department | 26 (12.9) | ||

| Senior physician | 89 (44.3) | ||

| Resident physician | 53 (16.6) | ||

| Total | 319 (100.0) | ||

Figure 1Participant flow diagram.

Accordingly, the population was divided into the following three subgroups: (1) respondents working in the hospital sector, (2) respondents working in private practice (excluding attending physicians) and (3) respondents working in private practice with attending duties in an obstetrics department (figure 2). As mentioned in the methods section, an exact response rate cannot be calculated. Based on the 2023 Foederatio Medicorum Helveticorum (FMH) statistics, the estimated response rates are 13% for all specialists (2064 total), 25% for hospital physicians (597 total) and 8% for private-practice physicians (1464 total) [16]. Data on resident physicians is unavailable, preventing calculation for this group.

Figure 2Group categorisation of the survey participants.

The linguistic distribution showed that 83% of the survey participants answered the questionnaire in German, 14% in French and 3% in Italian (table S1, available in the appendix in the PDF version at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4453), indicating that the regional distribution closely mirrored the Swiss healthcare landscape. The highest concentration of participants was from the Zurich region, accounting for approximately 30%. The most frequently obtained specialisations of the participants were operative obstetrics and gynaecology followed by feto-maternal medicine. Additional details, including data on work experience and hospital infrastructure, are also presented in Table S1.

On average, participants rated 3 out of 7 clinical parameters as important for indicating tocolysis (table 2, all physicians). Among these, premature preterm rupture of membranes before 34 weeks of gestation with contractions was identified as one of the most critical clinical parameters across all three groups of physicians. Cervical length under 25 mm and regular contractions were also significant factors, although their importance varied slightly between groups. A shortened cervical length played a larger role for private-practice physicians compared to the other two groups. Anamnestic factors and other parameters, such as bleeding in placenta previa or premature preterm rupture of membranes without contractions, were chosen less often in comparison. Responses under “Other” emphasised that contractions alone are insufficient and must be evaluated alongside cervical shortening, particularly when cervical length is extremely short (e.g. <15 mm for singletons, <20 mm for gemini) (table 2).

Table 2Indications, objectives and contraindications in tocolysis decision-making. Asked to all physicians. Second question only asked to physicians who selected >4 contractions in 20 minutes or 6 contractions in 60 minutes in the first question. All data shown as n (%).

| Which clinical parameter(s) are most important to you for the indication of tocolysis? (multiple-response question) | Hospital physicians (n = 201) | Attending physicians (n = 50) | Private-practice physicians (n = 68) | All physicians (n = 319) |

| Premature preterm rupture of membranes <34 weeks of gestation with contractions | 127 (63.2) | 39 (78.0) | 45 (66.2) | 211 (66.1) |

| Cervical length <25 mm (transvaginal ultrasound) | 113 (56.2) | 32 (64.0) | 48 (70.6) | 193 (60.5) |

| > 4 contractions in 20 minutes or 6 contractions in 60 minutes | 115 (57.2) | 23 (46.0) | 35 (51.5) | 173 (54.2) |

| Positive biochemical test (PartoSure®, FullTerm®) | 99 (49.3) | 16 (32.0) | 29 (42.6) | 144 (45.1) |

| Bleeding with placenta previa | 80 (39.8) | 22 (44.0) | 30 (44.1) | 132 (41.4) |

| History of preterm birth / late miscarriage | 41 (20.4) | 9 (18.0) | 19 (27.9) | 69 (21.6) |

| Premature preterm rupture of membranes <34 weeks of gestation without contractions | 36 (17.9) | 13 (26.0) | 18 (26.5) | 67 (21.0) |

| Other* | 15 (7.5) | 1 (2.0) | 5 (7.4) | 21 (6.6) |

| Do you differentiate between painful and non-painful contractions regarding your decision for the indication of tocolysis? (single-choice question) | Hospital physicians (n = 115) | Attending physicians (n = 23) | Private- practice physicians (n = 35) | All physicians (n = 173) |

| No | 53 (46.1) | 15 (65.2) | 24 (68.6) | 92 (53.2) |

| Yes, I assign a higher risk of preterm birth to painfulcontractions compared to non-painful contractions | 61 (53.0) | 8 (34.8) | 11 (31.4) | 80 (46.2) |

| Yes, I assign a higher risk of preterm birth to non-painful contractions compared to painful contractions | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.06) |

| What primary objectives do you pursue with tocolysis? (multiple-response question) | Hospital physicians (n = 201) | Attending physicians (n = 50) | Private-practice physicians (n = 68) | All physicians (n = 319) |

| Gaining time for lung maturation induction | 190 (94.5) | 47 (94.0) | 56 (82.4) | 293 (91.9) |

| Transfer to a perinatal centre | 105 (52.2) | 41 (82.0) | 46 (67.6) | 192 (60.2) |

| Prolongation of foetal development in utero | 73 (36.3) | 32 (64.0) | 47 (69.1) | 152 (47.6) |

| Meeting the patient’s needs | 5 (2.5) | 1 (2.0) | 4 (5.9) | 10 (3.1) |

| Other** | 5 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | 6 (1.9) |

| What are general contraindications for tocolysis for you? (multiple-response question) | Hospital physicians (n = 201) | Attending physicians (n = 50) | Private-practice physicians (n = 68) | All physicians (n = 319) |

| Sepsis | 177 (88.1) | 48 (96.0) | 60 (88.2) | 285 (89.3) |

| Chorioamnionitis | 178 (88.6) | 43 (86.0) | 59 (86.8) | 280 (87.8) |

| Severe preeclampsia | 152 (75.6) | 46 (92.0) | 65 (95.6) | 263 (82.4) |

| Placental abruption | 162 (80.6) | 41 (82.0) | 57 (83.8) | 260 (81.5) |

| Maternal haemodynamic instability | 164 (81.6) | 43 (86.0) | 52 (76.5) | 259 (81.2) |

| Gestational age over 34+0 weeks within an uncomplicated pregnancy | 170 (84.6%) | 36 (72.0) | 48 (70.6) | 254 (79.6) |

| Pulmonary oedema | 139 (69.2) | 42 (84.0) | 57 (83.8) | 238 (74.6) |

| Gestational age below 22+0 weeks | 149 (74.1) | 35 (70.0) | 46 (67.6) | 230 (72.1) |

| Pathological cardiotocography (CTG) | 138 (68.7) | 38 (76.0) | 47 (69.1) | 223 (69.9) |

| Other*** | 7 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | 8 (2.5) |

| None | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.6) |

* Other: biochemical tests are not available in our private clinic; additional criteria must always be present in case of contractions; assessment of the overall situation, referral to a tertiary centre; consistency/“rigidity” of the cervix; contractions affecting the cervix (2×); cervical length and biochemical test; cervical length under 25 mm with contractions (2×); cervical length under 15 mm ± contractions (4×); cervical length under 15 mm in singleton pregnancies, under 20 mm in gemini; before 34 weeks of gestation; antenatal corticoid therapy, combination of the above indications (4×); premature preterm rupture of membranes before 34 weeks of gestation with contractions until lung maturation induction, recurrent bleeding with placenta previa and threatened preterm birth.

** Other: reduce the patient’s symptoms; prevention of preterm birth before 34 weeks of gestation; depends on gestational age.

*** Other: for sepsis, it depends on the focus; non-viable foetus; intrauterine foetal demise; foetal malformations (incompatible with survival); relative contraindication: sepsis (question of, cause, risk of preterm birth, treatable focus); gestational age <22 weeks as a relative contraindication with evaluation of additional parameters; treat the cause of sepsis, address maternal haemodynamic instability, and deliver in cases of severe preeclampsia; placental abruption: depending on the extent of the abruption and, of course, foetal compromise (then delivery).

Participants who identified regular contractions as an important criterion for tocolysis were asked if they differentiate between painful and non-painful contractions in their tocolysis decision. The majority indicated no differentiation, especially among attending and private-practice physicians. Hospital physicians, however, tended to make a distinction: 53% of them considered painful contractions as carrying a higher risk (table 2).

Gaining time for inducing foetal lung maturity was the most defined goal across all groups, with over 80% agreement in each. A higher percentage of attending physicians and private-practice physicians than hospital physicians cited transfer to a perinatal centre as a goal, aligning with the practical relevance of their respective practice settings. Over 70% of participants considered all listed options as contraindications for tocolysis. Gestational age beyond 34 weeks was more frequently identified as a contraindication by hospital physicians than by attending or private-practice physicians (table 2).

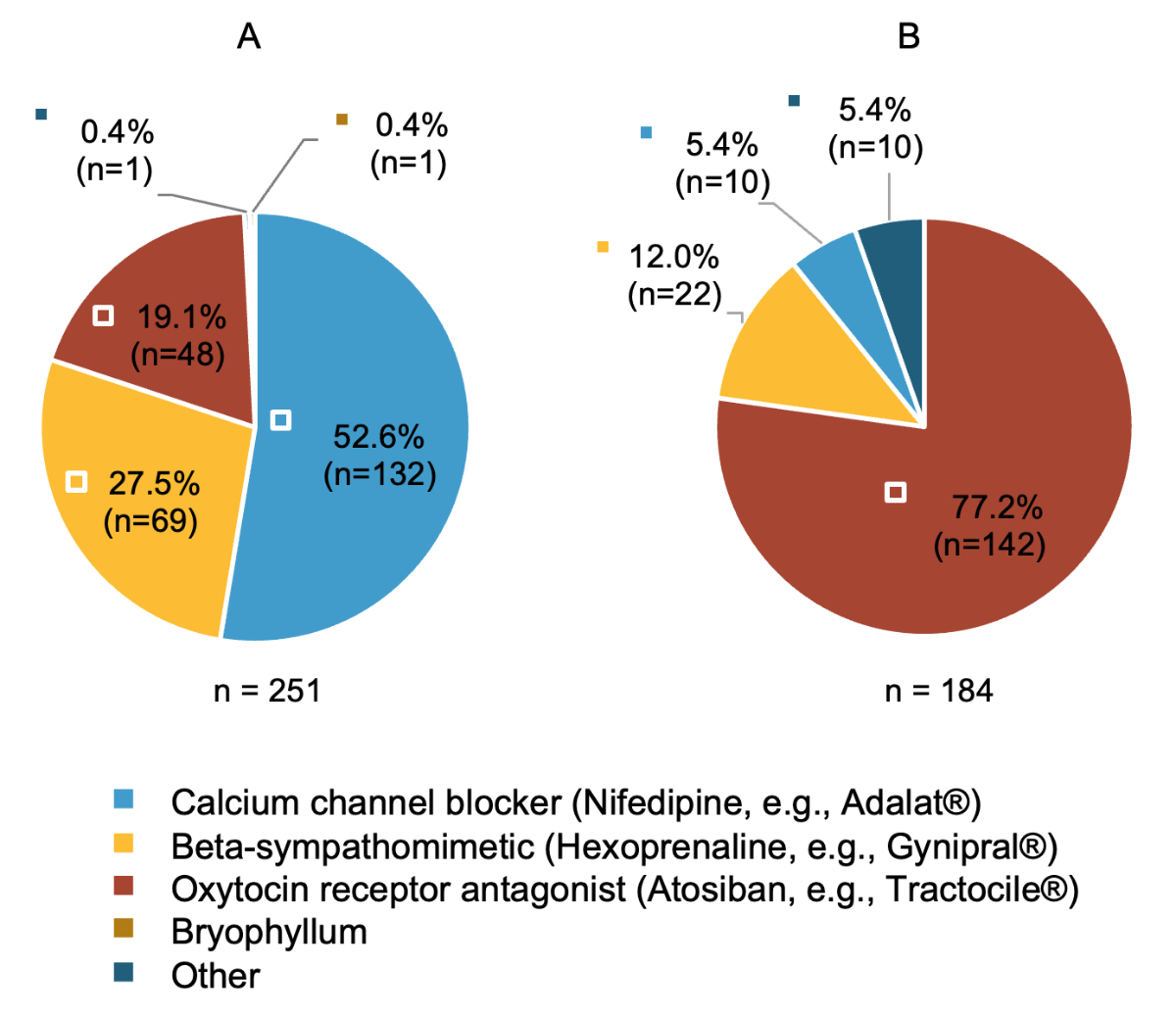

Calcium-channel blockers were the most frequently used tocolytic agents overall, particularly in hospital settings. Oxytocin receptor antagonists and beta-sympathomimetics were also commonly used, although their application varied by physician group and context (table S2).

Participants were asked to identify their first choice tocolytic in cases of acute threatened preterm birth in singleton pregnancies (figure 3A / table S3). This question was not posed to private-practice physicians due to the low prevalence of acute preterm birth cases in these settings. Calcium-channel blockers were preferred by approximately 50% of hospital and attending physicians for low-risk singleton pregnancies.

Figure 3Medications used as first-choice tocolytic according to pregnancy risk. Only asked to hospital and attending physicians. (A) Which medication do you use as the first-choice tocolytic in case of acute threatened preterm birth in the context of an uncomplicated singleton pregnancy? (n = 251) (B) Which medication do you use as the first-choice tocolytic in case of acute threatened preterm birth in the context of a high-risk pregnancy (multiples, extreme preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction [IUGR], bleeding due to placenta previa)? (n = 184) Only asked to participants reporting that they differentiate between their choice of tocolytic based on type of pregnancy in previous question (table S4 in appendix 1). “Other”: see table S3 in appendix 1, which is available at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4453.

Physicians were also queried on whether they differentiated their choice of tocolytic based on the presence of a high-risk pregnancy (e.g. multiple gestations, extreme preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction). Overall, 73% of hospital and attending physicians reported doing so (table S4). In high-risk pregnancies, oxytocin receptor antagonists were more frequently preferred, especially in cases of multiple gestations or specific complications (figure 3B / table S3).

Participants were asked about observed side effects of tocolytic agents (table S5). Beta-sympathomimetics were frequently observed with cardiovascular side effects, with 94% of observed effects classified as cardiac arrhythmias. Additionally, severe cardiovascular complications, such as angina pectoris or myocardial infarction, were reported in a small number of cases. Approximately 85% of surveyed physicians have already observed side effects such as hypotension, tachycardia or headaches within the use of calcium-channel blockers. Among the 33 physicians who reported side effects associated with indomethacin, premature closure of the ductus arteriosus was noted in 76% of cases. Two physicians observed (temporary) oligohydramnios. Oxytocin receptor antagonists were generally considered to be well tolerated; however, about 50% of observed side effects included nausea and vomiting, and 46% involved hypotension and/or tachycardia.

Most physicians selected tocolytics based on guideline recommendations or perceived efficacy. Factors such as minimal maternal side effects, practicality, Swissmedic approval, drug costs and minimal foetal side effects were less frequently mentioned as primary considerations (table S6).

The most common method of monitoring tocolytic efficacy was the cardiotocography (CTG) / tocogram, followed by cervical length measurements. Hospital physicians considered subjective patient perception as monitoring method more often (66%) than attending physicians (34%). Vaginal examinations and biochemical tests, such as PartoSure®, were rarely used (table S6).

Discontinuation of tocolysis typically occurred after completion of antenatal corticosteroid therapy and/or by 34 weeks of gestation. Only 60% of private-practice physicians stopped tocolysis by 34 weeks of gestation, indicating that approximately 40% would have continued therapy beyond the recommended timeframe. This represented the highest proportion among the groups extending therapy past the advised duration. In total, 20% of all physicians continued tocolytic treatment past the 34th week of gestation (table 3).

Table 3When to stop tocolytic administration. Asked to all physicians. All data shown as n (%).

| When do you usually stop a tocolytic therapy? (single-choice question) | Hospital physicians (n = 201) | Attending physicians (n = 50) | Private-practice physicians (n = 68) | All physicians (n = 319) |

| After successful lung maturation induction and/or from 34+0 weeks of gestation | 183 (91.0) | 32 (64.0) | 41 (60.3) | 256 (80.0) |

| From 35+0 weeks of gestation | 9 (4.5) | 14 (28.0) | 13 (19.1) | 36 (11.3) |

| From 36+0 weeks of gestation | 8 (4.0) | 4 (8.0) | 10 (14.7) | 22 (6.9) |

| Beyond 37+0 weeks of gestation | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (5.9) | 5 (1.6) |

Physicians were also asked about the gestational age at which they usually start and stop antenatal corticosteroid treatment (table S7 and table S8). Most hospital physicians initiated antenatal corticosteroid treatment between 23+5 and 24+0 weeks of gestation. Among attending physicians, 46% started administration at 24+0 weeks of gestation, representing the earliest time most of them considered suitable for antenatal corticosteroid treatment. The majority of hospital and attending physicians continued antenatal corticosteroid treatment until 33+6 or 34+0 weeks of gestation, representing the most common endpoint for both groups. However, some physicians extended administration beyond this point, particularly attending physicians (up to 37 weeks of gestation in 20% of cases). A “rescue dose” of antenatal corticosteroid treatment was administered by 57% of physicians, with hospital physicians doing so more frequently than attending physicians. Most adhered to the guideline-recommended dosages of 1 × 12 mg or 2 × 12 mg of betamethasone 24 hours apart, while a minority reported using alternative regimens (table 4).

Table 4Practice and dosage of repeat lung maturation induction (“rescue dose”) in cases of renewed threatened preterm birth. First question asked to hospital and attending physicians. Second question only asked to hospital and attending physicians reporting that they administer a “rescue dose” in case of renewed threatened preterm birth in previous question. All data shown as n (%).

| Do you administer a repeat course of lung maturation induction (“rescue dose”) in the event of renewed threatened preterm birth? (single-choice question) | Hospital physicians (n = 201) | Attending physicians (n = 50) | Hospital and attending physicians (n = 251) |

| No | 74 (36.8) | 34 (68.0) | 108 (43.0) |

| Yes | 127 (63.2) | 16 (32.0) | 143 (57.3) |

| At what dosage do you administer a rescue dose? (multiple-response question) | Hospital physicians (n = 127) | Attending physicians (n = 16) | Hospital and attending physicians (n = 143) |

| 1 × 12 mg betamethasone | 74 (58.3) | 8 (50.0) | 82 (57.3) |

| 2 × 12 mg betamethasone at 24 hours interval | 37 (29.1) | 7 (43.8) | 44 (30.8) |

| Other* | 22 (17.3) | 1 (6.3) | 23 (16.1) |

| No dosage selected | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) |

* Other: according to referring hospital; 1 × 12 mg dexamethasone (3×); 2 × 16 mg dexamethasone (5×); 1 × 16 mg dexamethasone (2×); depending on availability; only if last antenatal corticoid treatment is more than 6 weeks ago (2×); only if first antenatal corticoid treatment was given <28 weeks of gestation and already more than 2 weeks ago (2×); only if first antenatal corticoid treatment was administered between 24 and 27 weeks of gestation, the two doses of antenatal corticosteroid treatment are administered between 28 and 34 weeks of gestation. If the first antenatal corticosteroid treatment was administered between 28 and 34 weeks of gestation, there was no more rescue antenatal corticoid treatment (2×).

Both hospital and attending physicians were surveyed regarding their practice of maintenance tocolysis (tocolysis >48 hours). While the narrow majority reported not performing maintenance tocolysis, 46% indicated its use. Among these, physicians were nearly evenly divided between continuing the initially administered medication and switching to an alternative. The predominant rationale was specific clinical indications, followed by the management of pregnancies in early gestational weeks. Organisational considerations, such as avoiding patient transfers or facilitating in-hospital delivery, also played a role. Calcium-channel blockers were the most frequently used agents, with beta-sympathomimetics and oxytocin receptor antagonists being less commonly employed (table 5).

Table 5Maintenance tocolysis: practice patterns, indications and preferred agents among physicians. All questions only asked to hospital and attending physicians. Third and fourth question only asked to hospital and attending physicians reporting that they perform maintenance tocolysis in first question. All data shown as n (%).

| Do you perform maintenance tocolysis? (= tocolysis >48 hours) (single-choice question) | Hospital physicians (n = 201) | Attending physicians (n = 50) | Hospital and attending physicians (n = 251) |

| Yes | 91 (45.3) | 24 (48.0) | 115 (45.8) |

| No | 110 (54.7) | 26 (52.0) | 136 (54.2) |

| If you perform maintenance tocolysis, which tocolysis sequence do you normally use? (single-choice question) * | Hospital physicians (n = 91) | Attending physicians (n = 24) | Hospital and attending physicians (n = 115) |

| The same as initially started | 46 (50.5) | 13 (54.2) | 59 (51.3) |

| Switch to a different tocolytic | 45 (49.5) | 11 (45.8) | 56 (48.7) |

| For which reason(s) do you perform maintenance tocolysis? (multiple-response question) | Hospital physicians (n = 91) | Attending physicians (n = 24) | Hospital and attending physicians (n = 115) |

| For specific indications (e.g. bleeding with placenta praevia, amniotic sac prolapse, multiple pregnancies) | 75 (82.4) | 16 (66.7) | 91 (79.1) |

| In early weeks of gestation (before 28 weeks) | 50 (54.9) | 17 (70.8) | 67 (58.3) |

| At patient’s request | 16 (17.6) | 5 (20.8) | 21 (18.3) |

| Other reasons * | 16 (17.6) | 3 (12.5) | 19 (16.5) |

| When performing maintenance tocolysis, which tocolytic do you usually use? (multiple-response question) | Hospital physicians (n = 91) | Attending physicians (n = 24) | Hospital and attending physicians (n = 115) |

| Calcium-channel blocker (nifedipine, e.g. Adalat®) | 89 (97.8) | 19 (35.2) | 108 (93.9) |

| Bryophyllum | 31 (34.1) | 15 (27.8) | 46 (40.0) |

| Magnesium (oral) | 24 (26.4) | 10 (18.5) | 34 (29.6) |

| Beta-sympathomimetic (hexoprenaline, e.g. Gynipral®) | 25 (27.5) | 8 (14.8) | 33 (28.7) |

| Oxytocin receptor antagonist (atosiban, e.g. Tractocile®) | 10 (11.0) | 2 (3.7) | 12 (10.4) |

| Other reasons ** | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.7) |

* Other: avoid transfers outside the canton; long distance to hospital; for transfer purposes; no stop of tocolysis at night because of triplets; in practice, nifedipine is often continued beyond 48 hours if contractions persist, atosiban is typically stopped after 48 hours; no neonatology on site; if nifedipine proves insufficient; repeat contractions after stopping first tocolysis (3×); in outpatient setting oral nifedipine; extend to 34th week of gestation if you are close to it; extremely short cervix length; only maintenance tocolysis with nifedipine; for further maturation of the foetus in utero (2×); continue until reaching 35–36+0 weeks of gestation to enable birth at our facility.

** Other: sometimes others too; preferentially nifedipine.

The second last section of the questionnaire enquired how participants manage tocolysis in specific situations, such as premature preterm rupture of membranes without contractions (table 6) or during a cervical cerclage (table S8). In 35%, tocolysis due to premature preterm rupture of membranes <34 weeks of gestation without contractions was not performed. Many physicians (nearly 50%) administered tocolysis exclusively during corticosteroid therapy for foetal lung maturation. Maintenance tocolysis in this context was rare and often decided individually.

Table 6Tocolysis performed in patients with premature preterm rupture of membranes without contractions and after tocolysis failure. Only asked to hospital and attending physicians. All data shown as n (%).

| Do you perform tocolysis in patients with premature preterm rupture of membranes <34 weeks of gestation and without uterine activity, and if so for how long? (single-choice question) | Hospital physicians (n = 201) | Attending physicians (n = 50) | Hospital and attending physicians (n = 251) |

| No | 73 (36.3) | 15 (30.0) | 88 (35.1) |

| Yes – Only for the duration of lung maturation induction | 102 (50.7) | 19 (38.0) | 121 (48.2) |

| Yes – For ≥48 hours | 6 (3.0) | 3 (6.0) | 9 (3.6) |

| Yes – On a case-by-case basis | 20 (10.0) | 13 (26.0) | 33 (13.1) |

| If tocolysis is not effective (tocolysis failure): (single-choice question) | Hospital physicians (n = 201) | Attending physicians (n = 50) | Hospital and attending physicians (n = 251) |

| I stop the initial tocolysis and administer a different tocolytic | 133 (66.2) | 34 (68.0) | 167 (66.5) |

| I stop tocolysis | 45 (22.4) | 10 (20.0) | 55 (21.9) |

| I continue the initial tocolysis and additionally administer a second tocolytic | 21 (10.4) | 5 (10.0) | 26 (10.4) |

| I continue tocolysis until delivery | 2 (1.0) | 1 (2.0) | 3 (1.2) |

In the event of ineffective initial tocolysis (tocolysis failure), 2/3 of responding physicians opted to discontinue the initial tocolytic and administer an alternative agent (table 6). A smaller proportion chose to stop tocolysis entirely and only 10% of respondents continued the initial tocolytic and added a second agent.

Table 7 summarises data on the guidelines followed by participants, their recommendations after hospitalisation and the role of bed rest during tocolysis. The most commonly referenced sources for guidance were hospital-specific standard operating procedures (SOPs) and the Swiss Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics expert letter No. 41. Bed rest during tocolysis was recommended by nearly half of the respondents. Post-hospital care practices included issuing sick leave and close monitoring by colleagues in private practice, while reduced physical activity and progesterone therapy for a shortened cervix (<25 mm) were also commonly recommended. Bed rest played a minimal role in post-hospital care, mentioned by only 3% of respondents.

Table 7Additional recommendations given by the participating physicians and the guidelines they followed. All data shown as n (%).

| If tocolysis is indicated, I most closely follow: (multiple-response question) | Hospital physicians (n = 201) | Attending physicians (n = 50) | Private-practice physicians (n = 68) | All physicians (n = 319) |

| Internal Standard Operating Procedures / Guidelines | 168 (83.6) | 29 (58.0) | 26 (38.2) | 223 (69.9) |

| SGGG Expert Letter No. 41 “Tocolysis for Preterm Labor” [21]* | 98 (48.8) | 34 (68.0) | 54 (79.4) | 186 (58.3) |

| S2k-Guideline “Prevention and Treatment of Preterm Birth” | 64 (31.8) | 11 (22.0) | 21 (30.9) | 96 (30.1) |

| International guidelines (ACOG, RCOG, NICE, Up-To-Date, etc.) | 50 (24.9%) | 11 (22.0) | 12 (17.6) | 73 (22.9) |

| My own professional experience | 25 (12.4%) | 18 (36.0) | 23 (33.8) | 66 (20.7) |

| Expertise of experienced colleagues | 49 (24.4) | 5 (10.0) | 11 (16.2) | 65 (20.4) |

| Other** | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | 3 (4.4) | 4 (1.3) |

| Do you recommend bed rest tocolysis? (single-choice question) | Hospital physicians (n = 201) | Attending physicians (n = 50) | Private-practice physicians (n = 68) | All physicians (n = 319) |

| Yes | 68 (33.8) | 31 (62.0) | 35 (51.5) | 134 (42.0) |

| No | 133 (66.2) | 19 (38.0) | 33 (48.5) | 185 (58.0) |

| What recommendation(s) do you provide at discharge regarding the procedure for patients who required tocolysis? (multiple-response question) | Hospital physicians (n = 201) | Attending physicians (n = 50) | Private-practice physicians | Hospital and attending physicians (n = 319) |

| 100% sick leave | 183 (91.0) | 49 (98.0) | N/A | 232 (92.4) |

| Close monitoring by private-practice physician | 161 (80.1) | 45 (90.0) | N/A | 206 (82.1) |

| Restricted activity | 159 (79.1%) | 47 (94.0) | N/A | 206 (82.1) |

| Progesterone (oral/vaginal) if cervix <25 mm | 99 (49.3) | 31 (62.0) | N/A | 130 (51.8) |

| Close monitoring by hospital | 51 (25.4) | 5 (10.0) | N/A | 56 (22.3) |

| Bed rest | 3 (1.5) | 3 (6.0) | N/A | 6 (2.4) |

| None | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A | 2 (0.8) |

N/A = not applicable (question not asked to this group of physicians); ACOG: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; RCOG: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; SGGG: Swiss Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics.

* SGGG expert letter No. 41 [21]: if this is justifiable without risk in the periphery, otherwise transfer.

** Other: according to the guidelines of the clinic (University Hospital Zurich [45]), where I refer the patient for assessment (2×).

Our analysis suggests that obstetricians represented in this study demonstrate a high level of adherence to national and international guidelines across multiple aspects of care. Specifically, 80% of the survey participants follow the guidelines regarding the timing of tocolysis, 84% adhere to recommendations for the administration of antenatal corticosteroid treatment and 87% comply with the guidelines for the administration of rescue doses. The survey identified premature preterm rupture of membranes before 34 weeks of gestation with contractions as the most critical tocolysis indicator, citing gaining time for foetal lung maturity as the primary goal, and sepsis, chorioamnionitis and severe preeclampsia were emphasised as significant contraindications. In cases of acute threatened preterm birth in singleton pregnancies, calcium-channel blockers were the most commonly selected first-choice tocolytic, with beta-sympathomimetics as the secondary preference. When considering high-risk pregnancies, the majority adapted their tocolytic choice, favouring oxytocin receptor antagonists, particularly for multiple gestations.

In routine clinical practice, maintenance tocolysis is still performed by approximately half of all participants working in the hospital sector with beta-sympathomimetics being used in nearly a third of cases, despite above-mentioned international guidelines advising against this practice due to a lack of evidence [6] or the potential for severe maternal side effects [17–19]. The low percentage of cases using oxytocin receptor antagonists for maintenance tocolysis in Switzerland might be attributed to the fact that its use beyond the approved maximum duration of 48 hours would classify as off-label use [20]. Furthermore, some discrepancies remain, particularly regarding the continuation of tocolysis beyond 34 weeks of gestation, a practice that is still undertaken by 20% of all participating physicians. This contradicts the recommendations outlined in the Swiss Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics expert letter No. 41 and the international guidelines [6, 21, 22].

The observed discrepancies between recommendations and reported practices in Switzerland might suggest uncertainty, a lack of agreement with current recommendations or a greater emphasis on the benefits of prolonging pregnancy beyond 34 weeks of gestation. The high proportion of individual reasons (e.g. organisational or infrastructural factors) suggests that pragmatic considerations influence the clinical decision.

Survey responses indicate that physicians often initiated antenatal corticosteroid treatment between 24+0 weeks of gestation and commonly continued until 34+0 weeks of gestation, with a minority extending administration up to 37+0 weeks of gestation. Rescue administration was given by the majority of physicians (about 60%) and adherence to guideline-recommended dosages was high, although some variability in dosing practices existed. In comparison, the current literature underscores a similar preference for initiating corticosteroid treatment at 24+0 weeks of gestation and supports the use of rescue administration within a vague framework largely due to lack of evidence [23–28].

When confronted with tocolytic failure, most physicians preferred to switch to an alternative tocolytic when the initial agent proved ineffective, suggesting a belief in the potential efficacy of different tocolytic agents for individual patients. This aligns with existing literature that emphasises variability in patient responses to tocolytic therapy, supporting an individualised treatment approach [29]. In contrast, the small proportion that opted for combination therapy may reflect concerns regarding increased side effects or reduced efficacy, as highlighted in some studies [18, 30].

In response to the question of whether bed rest is recommended during tocolysis, 42% of survey participants answered that they do indeed recommend it. The current guidelines and literature on the matter advise against routine bed rest, as there are no significant benefits and the practice may pose substantial health risks (e.g. thrombosis, muscle atrophy, psychological strain) [31, 32]. In consideration of the documented incidence of side effects associated with various tocolytics, these findings align with those stated in the medicinal product information and the literature [33].

Compared to the existing literature, our study offers an analysis of threatened preterm birth management practices in Switzerland, highlighting both adherence and deviations from established guidelines. Similar to the findings of international studies [10, 11, 13, 34, 35], our results suggest that while clinical practice is informed by national and international guidelines, discrepancies exist, particularly regarding the continuation of tocolysis beyond 34 weeks of gestation – a practice identified in our study and noted by Nazifovic et al. [12] in Austria as indicative of a gap between evidence-based recommendations and clinical application. Our findings also align closely with the Germany- and Austria-wide survey of Stelzl et al. [7–9], demonstrating that maintenance tocolysis beyond the recommended period is still prevalent. In addition, the pattern of first-line tocolytic substance use shows strong similarities between countries. The observed similarities between Switzerland, Germany and Austria may be partly due to shared clinical traditions, overlapping training structures and the joint development of guidelines by societies such as the German Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Swiss Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics and Austrian Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. Linguistic and cultural ties may also support similar dissemination of clinical practices.

The question of why there are these discrepancies between practice and guidelines remains unclear in some parts. In contrast to maintenance tocolysis, which is often only given based on specific (high risk) situations, the restraint in the administration of tocolysis after 34 weeks of gestation has not yet been achieved in the study population. We suspect that despite the clear evidence showing that tocolysis after 34 weeks of gestation offers no foetal advantage, the idea of a potential benefit from prolonging pregnancy enduringly persists. To potentially address the observed discrepancies, targeted educational initiatives are essential to bridge the gap between guidelines and actual practice. Greater dissemination of the current guidelines and training programmes could promote a more uniform adherence to recommendations. Additionally, reviewing Standard Operating Procedures to align them more closely with national and international guidelines would help mitigate regional differences and ensure evidence-based care.

Discrepancies between clinical practice and evidence-based guidelines may also stem from hierarchical information flow in hospitals. Residents often adopt practices conveyed verbally by senior consultants, hesitating to challenge authority, which can perpetuate outdated methods. While reliance on senior guidance is understandable given residents’ limited experience, studies by West and Swennen et al. [36, 37] highlight how such structures hinder evidence-based practice adoption.

In addition to local dynamics, structural factors at the national level may also play a role. In Switzerland, clinical recommendations are often communicated through official expert letters published by the Swiss Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. These concise documents – such as Expert Letter No. 41 on tocolysis [21] – are widely circulated and commonly referenced in clinical settings and local Standard Operating Procedures. Although they are highly influential, they do not follow a formalised methodological grading process, such as those used in the development of S1–S3 guidelines under the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF) framework [38].

Moreover, Switzerland currently lacks a central institution responsible for the systematic implementation, dissemination or monitoring of such recommendations. Nationwide quality assurance programmes in perinatal care are also limited in scope. While promising initiatives such as the Swiss Neonatal Quality Cycle exist [39], a structured and nationwide monitoring system is still absent.

In contrast, Germany has implemented structured systems for both the coordination of guideline development and the monitoring of care quality. Guidelines are developed under the AWMF, often with participation from the Swiss Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics and Austrian Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, and follow a graded evidence-based process [38]. Perinatal care quality is further monitored through mandatory national quality assurance programmes, such as Germany’s perinatal quality system coordinated by the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA) and implemented by the Institute for Quality Assurance and Transparency in Healthcare (Institut für Qualitätssicherung und Transparenz im Gesundheitswesen [IQTIG]) [40]. This model may offer valuable insights for strengthening evidence-based and quality-orientated perinatal care in Switzerland.

A strength of this survey is its attempt to represent Swiss obstetricians, allowing for an analysis that reflects varied practices and perspectives across the country. The inclusion of physicians from different language regions provides a well-rounded view of clinical practices in Switzerland. While most of the responses come from the German-speaking region, the French- and Italian-speaking respondents add valuable insights, albeit with a slight underrepresentation compared to national demographics [41]. Additionally, the sample includes doctors from both hospitals and private practices, encompassing all professional levels from resident physicians to chief physicians. This diverse representation ensures that the findings provide a detailed overview of practices and challenges in preterm birth management throughout Switzerland.

A key limitation of this study is the potential for selection bias. Although the response rate could be estimated using FMH statistics, the lack of comprehensive data on the characteristics of the entire population precludes a direct comparison. This limitation may affect the representativeness of the sample, limiting the generalisability of the findings. Furthermore, the relatively low response rate may amplify these concerns, as it increases the likelihood that only certain subsets of the population participated. Additionally, responses may be biased towards practices aligning with guidelines, reflecting social desirability bias observed in similar studies [42, 43]. Another limitation concerns the potential overrepresentation of specific clinical environments. Since chief physicians distributed the survey within their teams, multiple responses from the same institution may reflect shared Standard Operating Procedures, introducing response clustering. Additionally, private-practice gynaecologists were reached through local networks and an internal directory due to the lack of a national registry. This may have led to a geographically or professionally skewed sample. Both aspects could limit the national representativeness and generalisability of the findings.

As of November 2024, the authors became aware of a similar survey conducted in Switzerland between June and December 2022, uploaded to the Johannes Kepler University Linz online library in August 2023 [44]. To our knowledge, this survey, with a small sample size (n = 22) and conducted in German only, has not been published in a peer-reviewed journal. In contrast, our study included a larger, more representative population, encompassing all language regions of Switzerland and targeting hospital physicians, attending physicians and private-practice physicians to capture variations in clinical practice.

Finally, as multiple-choice questions are designed to assess academic knowledge and everyday clinical practice is inherently more complex, the data collected must be interpreted with appropriate caution.

Taken together, the results of this survey suggest that obstetricians within our study population largely adhere to national and international guidelines for preterm birth management, with over 80% following recommendations regarding the timing of tocolysis, the administration of antenatal corticosteroid treatment, and rescue doses. Nevertheless, the analysis highlights discrepancies in the use of tocolytics, particularly in the context of maintenance tocolysis and other strategies for managing preterm birth across Switzerland. These findings underscore the potential value of targeted training initiatives and the development of updated Standard Operating Procedures to address these gaps. Harmonising practices through such measures could reduce regional inconsistencies, ensure closer alignment with evidence-based guidelines and ultimately improve outcomes in the management of preterm birth.

The deidentified study data, including the SPSS dataset and an accompanying codebook, is available via the open-access repository Zenodo. The dataset can be accessed under the following DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14728566.

We would like to extend our sincerest gratitude to all those who participated in the survey, without whom this cross-sectional study would not have been possible. We would also like to express our gratitude to Dr T. Eggimann (Secretary General of the Swiss Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics) and Dr J. Mathis (President of the Chief Physicians’ Conference of the Swiss Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics) for their invaluable assistance in the promotion and distribution of the survey.

This study received no funding.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. – APSW has received research funding during the last three years for Bryophyllum projects from Weleda AG, the company producing Bryophyllum 50% tablets. No other potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. McCormick MC. The contribution of low birth weight to infant mortality and childhood morbidity. N Engl J Med. 1985 Jan;312(2):82–90.

2. Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008 Jan;371(9606):75–84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4

3. Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ. Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes. Science. 2014;345(6198):760-5. Epub 20140814. doi: . PubMed PMID: 25124429; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4191866.

4. Haas DM, Caldwell DM, Kirkpatrick P, McIntosh JJ, Welton NJ. Tocolytic therapy for preterm delivery: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345(oct09 2):e6226-e. doi: .

5. Haas DM, Golichowski AM, Imperiale TF, Kirkpatrick PR, Zollinger TW, Klein RW. Tocolytic Therapy: A Meta-Analysis and Decision Analysis. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2009;114(1):171. doi: . PubMed PMID: 00006250-200907000-00038. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e318199924a

6. Prevention and therapy of preterm labour. Guideline of DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG (S2k-level, AWMF Registry No.015/025, July 2022).

7. Enengl S, Rath W, Kehl S, Oppelt P, Mayr A, Stroemer A, et al. Differences between Current Clinical Practice and Evidence-Based Guideline Recommendations Regarding Tocolysis - an Austria-wide Survey. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2025;85(1):47-55. Epub 20241128. doi: . PubMed PMID: 39758118; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC11695098.

8. Stelzl P, Kehl S, Oppelt P, Maul H, Enengl S, Kyvernitakis I, et al. Do obstetric units adhere to the evidence-based national guideline? A Germany-wide survey on the current practice of initial tocolysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2022 Mar;270:133–8.

9. Stelzl P, Kehl S, Oppelt P, Mayr A, Fleckenstein T, Maul H, et al. Maintenance tocolysis, tocolysis in preterm premature rupture of membranes and in cervical cerclage - a Germany-wide survey on the current practice after dissemination of the German guideline. J Perinat Med. 2023 Mar;51(6):775–81.

10. Hui D, Liu G, Kavuma E, Hewson SA, McKay D, Hannah ME. Preterm labour and birth: a survey of clinical practice regarding use of tocolytics, antenatal corticosteroids, and progesterone. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007 Feb;29(2):117–24. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32384-2

11. Lee HH, Yeh CC, Yang ST, Liu CH, Chen YJ, Wang PH. Tocolytic Treatment for the Prevention of Preterm Birth from a Taiwanese Perspective: A Survey of Taiwanese Obstetric Specialists. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Apr;19(7):4222.

12. Nazifovic E, Husslein H, Lakovschek I, Heinzl F, Wenzel-Schwarz E, Klaritsch P, et al. Differences between evidence-based recommendations and actual clinical practice regarding tocolysis: a prospective multicenter registry study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018 Nov;18(1):446.

13. Parant O, Maillard F, Tsatsaris V, Delattre M, Subtil D, Goffinet F; EVAPRIMA Group. Management of threatened preterm delivery in France: a national practice survey (the EVAPRIMA study). BJOG. 2008 Nov;115(12):1538–46.

14. Hämmig O. Explaining burnout and the intention to leave the profession among health professionals - a cross-sectional study in a hospital setting in Switzerland. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):785. Epub 20181019. doi: . PubMed PMID: 30340485; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6194554.

15. Hurst SA, Zellweger U, Bosshard G, Bopp M. Medical end-of-life practices in Swiss cultural regions: a death certificate study. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):54. Epub 20180420. doi: . PubMed PMID: 29673342; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5909244.

16. Hostettler S, Kraft E. FMH-Ärztestatistik 2023 – 40 % ausländische Ärztinnen und Ärzte. Schweiz Arzteztg. 2024.

17. Herzog S, Cunze T, Martin M, Osmers R, Gleiter C, Kuhn W. Pulsatile vs. continuous parenteral tocolysis: comparison of side effects. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999 Aug;85(2):199–204.

18. Vogel JP, Nardin JM, Dowswell T, West HM, Oladapo OT. Combination of tocolytic agents for inhibiting preterm labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014(7). doi: . PubMed PMID: CD006169.

19. Vogel JP, Oladapo OT, Manu A, Gulmezoglu AM, Bahl R. New WHO recommendations to improve the outcomes of preterm birth. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(10):e589-90. Epub 20150823. doi: . PubMed PMID: 26310802.

20. Anlage zur Genehmigung für das Inverkehrbringen von Medikamenten im Gemeinschaftsregister. EPAR - Enbrel. In: Commission E, editor. 2006.

21. Hösli I, Sperschneider C, Drack G, Zimmermann Z, Surbek D, Irion O. SGGG Expertenbrief Nr. 41: Tokolyse bei vorzeitiger Wehentätigkeit [SGGG Expert Letter No. 41: Tocolysis for preterm labour]. Forum gynécologie suisse. 2013;3:16-19. Available from: https://www.sggg.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/Dokumente/4_NEWS/2_Mitgliedermagazin/forum_sggg_3_2013_web.pdf

22. Prediction and Prevention of Spontaneous Preterm Birth. Prediction and Prevention of Spontaneous Preterm Birth: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 234. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Aug;138(2):e65–90. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004479

23. Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Thom EA, Blackwell SC, Tita AT, Reddy UM, Saade GR, et al.; NICHD Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units Network. Antenatal Betamethasone for Women at Risk for Late Preterm Delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016 Apr;374(14):1311–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1516783

24. Humbeck C, Jonassen S, Bringewatt A, Pervan M, Rody A, Bossung V. Timing of antenatal steroid administration for imminent preterm birth: results of a prospective observational study in Germany. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2023 Sep;308(3):839–47. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-022-06724-9

25. Cojocaru L, Chakravarthy S, Tadbiri H, Reddy R, Ducey J, Fruhman G. Use, misuse, and overuse of antenatal corticosteroids. A retrospective cohort study. Journal of Perinatal Medicine. 2023;0.

26. McGoldrick E, Stewart F, Parker R, Dalziel SR. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;12(12):CD004454. Epub 20201225. doi: . PubMed PMID: 33368142; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8094626.

27. Crowther CA, Haslam RR, Hiller JE, Doyle LW, Robinson JS; Australasian Collaborative Trial of Repeat Doses of Steroids (ACTORDS) Study Group. Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome after repeat exposure to antenatal corticosteroids: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006 Jun;367(9526):1913–9.

28. Asztalos EV, Murphy KE, Willan AR, Matthews SG, Ohlsson A, Saigal S, et al.; MACS-5 Collaborative Group. Multiple courses of antenatal corticosteroids for preterm birth study: outcomes in children at 5 years of age (MACS-5). JAMA Pediatr. 2013 Dec;167(12):1102–10.

29. Manuck TA. Pharmacogenomics of preterm birth prevention and treatment. BJOG. 2016;123(3):368-75. Epub 20151106. doi: . PubMed PMID: 26542879; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4729635.

30. de Heus R, Mol BW, Erwich JJ, van Geijn HP, Gyselaers WJ, Hanssens M, et al. Adverse drug reactions to tocolytic treatment for preterm labour: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:b744. Epub 20090305. doi: . PubMed PMID: 19264820; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2654772.

31. Saccone G, Della Corte L, Cuomo L, Reppuccia S, Murolo C, Napoli FD, et al. Activity restriction for women with arrested preterm labor: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023 Aug;5(8):100954. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2023.100954

32. Sosa CG, Althabe F, Belizan JM, Bergel E. Bed rest in singleton pregnancies for preventing preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(3):CD003581. Epub 20150330. doi: . PubMed PMID: 25821121; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7144825.

33. Lamont CD, Jørgensen JS, Lamont RF. The safety of tocolytics used for the inhibition of preterm labour. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016 Sep;15(9):1163–73.

34. Cook CM, Peek MJ. Survey of the management of preterm labour in Australia and New Zealand in 2002. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004 Feb;44(1):35–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828X.2004.00173.x

35. Fox NS, Gelber SE, Kalish RB, Chasen ST. Contemporary practice patterns and beliefs regarding tocolysis among u.s. Maternal-fetal medicine specialists. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jul;112(1):42–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e318176158e

36. West E, Barron DN, Dowsett J, Newton JN. Hierarchies and cliques in the social networks of health care professionals: implications for the design of dissemination strategies. Soc Sci Med. 1999 Mar;48(5):633–46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00361-X

37. Swennen MHJ, van der Heijden GJMG, Boeije HR, van Rheenen N, Verheul FJM, van der Graaf Y, Kalkman CJ. Doctors’ Perceptions and Use of Evidence-Based Medicine: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Academic Medicine. 2013;88(9):1384-96. doi: . PubMed PMID: 00001888-201309000-00047.

38. Muche-Borowski C, Selbmann H, Nothacker M, Müller W, Kopp I. AWMF guidance manual and rules for guideline development. English version. 2012.

39. Adams M, Hoehre TC, Bucher HU; Swiss Neonatal Network. The Swiss Neonatal Quality Cycle, a monitor for clinical performance and tool for quality improvement. BMC Pediatr. 2013 Sep;13(1):152.

40. Gesundheitswesen IfQuTi. Bundesqualitätsbericht 2024 – QS-Verfahren Perinatalmedizin (QS–PM). Düsseldorf: IQTIG; 2024.

41. Hauptsprachen der Bevölkerung in der Schweiz im Jahr. 2022 [Internet]. Statista. 2024 [cited 12.11.2024]. Available from: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/216829/umfrage/sprachen-in-der-schweiz/#:~:text=Im%20Jahr%202022%20sprachen%2061,Italienisch%20mit%208%2C2%20Prozent

42. Gower T, Pham J, Jouriles EN, Rosenfield D, Bowen HJ. Cognitive biases in perceptions of posttraumatic growth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2022 Jun;94:102159.

43. Scott A, Jeon SH, Joyce CM, Humphreys JS, Kalb G, Witt J, Leahy A. A randomised trial and economic evaluation of the effect of response mode on response rate, response bias, and item non-response in a survey of doctors. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:126. Epub 20110905. doi: . PubMed PMID: 21888678; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3231767.

44. Schedl V. The use of initial tocolysis and maintenance tocolysis in preterm birth: guideline-based approach or off-label use-a survey on the current application in Switzerland/Author Valentina Schedl, Bsc. 2023.

45. Zimmermann R, editor. Handbuch Geburtshilfe: ein praxisnaher Ratgeber [Handbook of obstetrics: a practical Guide]3rd ed. Zurich: University Hospital Zurich; 2018.

The appendix is available in the PDF version of the article and the supplementary file is available for download as a separate file at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4453.