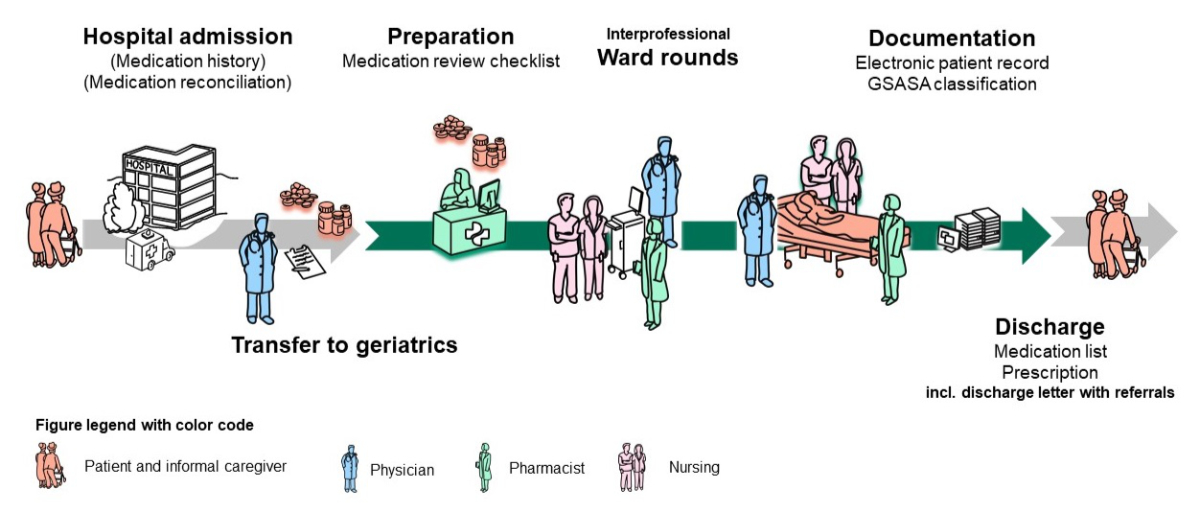

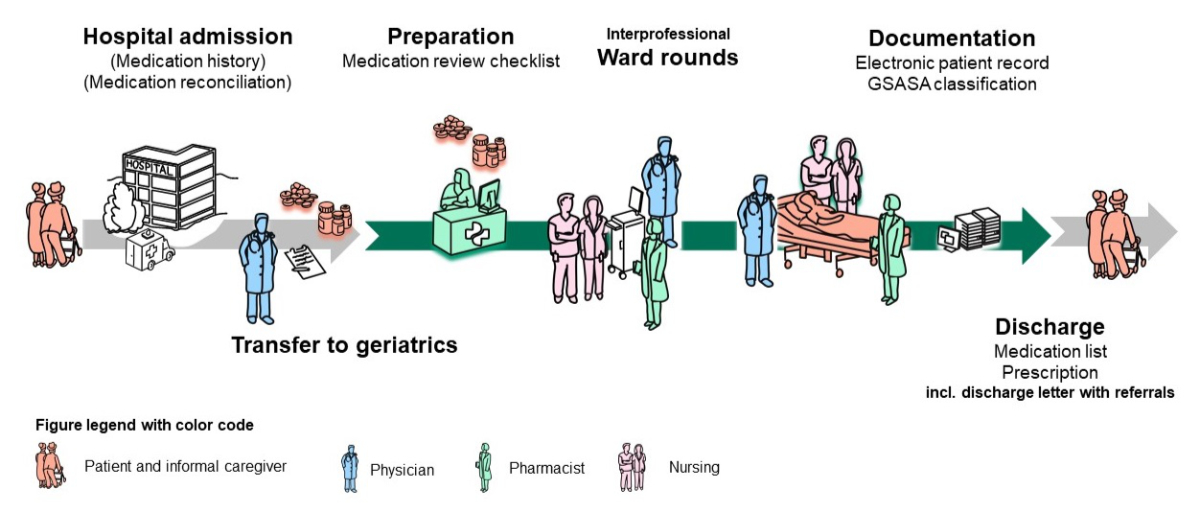

Figure 1Elements and sequence of the PharmVisit process.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4351

Older adult populations aged 75 or older are a particular challenge to daily medical care because of, among other things, the age-related physiological changes,characterised by impairment in the function of the many regulatory processes. Under the physiological stress that can occur in acute health conditions, homeostasis may not be maintained, leading to hospitalisation [1]. Medication-induced adverse effects may occur due to older adults’ altered pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. It is well documented that they are often prescribed medications that, though safe for younger patients, are potentially inappropriate considering their age [2, 3]. Furthermore, older adult patients are often multimorbid, polymedicated, frail and cognitively impaired – all risk factors for medication-related problems (MRPs), which encompass (preventable) medication errors and adverse drug reactions. When admitted into inpatient care, interfaces between institutions and healthcare professionals pose the additional risk of information gaps that could lead to medication discrepancies and potentially hazardous treatment errors [4]. Data from a 2019 study in Switzerland by Giannini et al. found, through medication reconciliation, at least one discrepancy with every patient, with an average of three medications omitted. Indeed, they determined that 21% of the discrepancies were clinically relevant, and 19% of those were significant, i.e. had the potential to cause a mild-to-moderate adverse effect [5].

Although geriatricians undergo specialised training to treat patients with polypharmacy that benefits this group [3], interprofessional activities like pharmacist-accompanied ward rounds can further improve medication safety among hospitalised older adult patients. In a study conducted on two internal medicine wards in Switzerland, clinical pharmacists identified a mean of 2.6 medication-related problems per patient, mostly drug-drug interactions (21%), untreated indications (18%), overdosing (16%) and drugs used without a valid indication (10%) [6].

A study published by Blum et al. in the scope of the international OPERAM project did provide comparable findings of a mean of 2.75 START/STOPP recommendations based on interprofessional medication review in older adults, albeit from general internal medicine [7].

The University Hospital of Bern’s Department of Geriatrics, therefore, agreed to host a pilot project – PharmVisit – and welcome clinical pharmacists on its weekly ward rounds. This project’s overall goal was to optimise medication safety by identifying additional potential medication-related problems. We thus aimed to characterise the pharmacists’ recommended interventions and determine physicians’ acceptance rates for them.

The Inselspital-University Hospital of Bern’s Department of Geriatrics (in Switzerland), consisting of one ward, predominantly treats patients older than 70. Patients are usually admitted to other departments because of an emergency in the ambulatory or long-term care setting. To meet the criteria for admission to the Department of Geriatrics, patients must be diagnosed with a specific geriatric syndrome, e.g. a gait disorder, a cognitive, visual or hearing impairment, or polypharmacy. At the time of transfer, the patients still need in-hospital treatment and are not yet in a condition to be discharged due to different factors. Because patients’ care has to cross different interfaces or undergo transitions of care, they are at a greater risk of medication-related problems. This is one of the reasons why the Department of Geriatrics welcomed the project’s clinical pharmacists on weekly ward rounds. The ward is organised into three sectors of 8–10 beds, with average hospital lengths of stay of 7–14 days. During this time, patients receive a daily training plan that includes physiotherapy, occupational therapy and group activities that aim to maintain and promote their independence.

The PharmVisit prospective quality improvement pilot study was conducted over the 11 months from the start of June 2023 to the end of April 2024, aiming for the inclusion of at least 145 patients and approximately 300 recommendations, assuming that at least two interventions per patient would be suggested, in order to have data with results comparable to a study performed in Switzerland earlier, albeit in internal medicine [6]. Clinical pharmacists attended interprofessional ward rounds approximately once per week. All had formal training in clinical pharmacy and at least one year of postgraduate professional experience.

The clinical pharmacists performed a systematic medication analysis of every eligible patient one day before the ward round based on the information in their electronic patient record and according to the Pharmaceutical Care Europe Networks (PCNE) definition of a Type 2b medication review [8]. For standardisation purposes, a checklist for medication review, based on the Medication Appropriateness Index [9], was provided to the clinical pharmacists (see appendix 1), who were supervised by a senior clinical pharmacist during their initial participation in the PharmVisit project.

Every patient on the participating geriatrics ward during the ward rounds prepared for by the clinical pharmacists was considered eligible for the project. No exclusion criteria were defined.

The hospital uses an electronic patient record system (EPIC, Epic Systems Corporation, https://www.epic.com) that is accessible to clinical pharmacists and enables PCNE Type 2b Advanced Medication Reviews [8].

PharmVisit ward rounds started with a discussion about the clinical pharmacist’s recommendations outside the patient’s room involving the physicians (mostly residents, but sometimes also a senior physician), the clinical pharmacist and a nurse. The discussion attempted to detect any medication-related problems like missing indications, dosing issues, drug-drug interactions, side effects, medication effectiveness and also covered adherence to guidelines, drug omissions and recommended interventions [8]. Recommendations were: accepted and noted directly in the EPIC system; or declined by the physicians present; or referred to senior physicians as topics for further discussion after the ward round; or delegated to the primary care physician in the discharge letter. Patients were also involved in the decision-making process. The PharmVisit process is shown in figure 1.

The clinical pharmacists documented the following items for each patient discussed during a PharmVisit ward round in a spreadsheet (Excel® for Microsoft Professional Plus 2016) according to the Swiss Association of Public Health Administration and Hospital Pharmacists (GSASA) classification system [10]: recorded problem, reason for intervention, the intervention suggested and the outcome pertaining to physician acceptance. In addition, they also tabulated the drugs involved (using their Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical or ATC code) in a spreadsheet (Excel® for Microsoft Professional Plus 2016) [10]. The complete classification system is shown in appendix 2. French and German versions are available online from https://www.gsasa.ch.

Physicians documented ward rounds in the electronic patient record.

The following patient data were systematically recorded in a spreadsheet in Excel® (Microsoft Professional Plus 2016) after ward rounds: the patient’s unique identification number, age, sex, number of comorbidities, diagnosis leading to hospital admission and number of medications. Outcome measures focused on descriptions of the clinical pharmacists’ recommendations and their acceptance by physicians. A recommendation was considered accepted when the decision to do so was made during ward rounds. The corresponding entry in the patient file was verified before the next ward round by one of the pharmacists. Verification required the unique patient identification number in order to access the patient’s electronic file. If the unique patient identifier was missing or wrong, the patient data could not be retrieved and it was considered missing data, leading to exclusion of that patient from our analysis. As a last step, patients were provided a consecutive number, anonymising the data irrevocably.

Figure 1Elements and sequence of the PharmVisit process.

Descriptive data analyses were performed in Excel®. Categorical variables were expressed using percentages, and continuous variables were reported using mean ± standard deviation (SD) and the median. We specifically analysed patient population characteristics pertaining to age and sex. We calculated the prevalence of the most common comorbidities. We counted regular and as-needed medications in order to calculate the extent of polypharmacy. The prevalence of the types of interventions suggested by pharmacists as well as their acceptance rate by physicians were tabulated. To characterise the pharmacists’ interventions, we also conducted an exploratory descriptive data analysis.

A study protocol has not been published separately.

The present study was performed per the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Cantonal Ethics Committee of Bern decided that an ethics review was not necessary as the study fell under the category of quality improvement projects and not under the Swiss Federal Human Research Act (ethics submission ID 2024-0056). This manuscript is structured according to the EQUATOR network’s Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQuIRE) guideline (https://www.equator-network.org) [11].

From June 2023 to April 2024, our clinical pharmacists recommended 480 potential medication interventions for 223 patients during 46 ward rounds. (Four additional patients were excluded due to missing or wrong patient identification numbers.)

The average patient age was 82, and 54% were men. Patients were predominantly transferred from the departments of General Internal Medicine (n = 129 or 58%), Neurology (n = 31 or 14%) and Orthopaedics (n = 20 or 9%). Patients had an average of 17 diagnoses (range: 6–42, median: 16). The top three diagnoses for admission to the geriatric ward were cerebrovascular events (n = 33 or 15%), fractures (n = 23 or 10%) and sepsis (n = 18 or 8%). Patients had a minimum of 2 and a maximum of 22 medications prescribed, with a median of 8. Patient characteristics are displayed in table 1.

Table 1Description of characteristics of patients included in the PharmVisit project.

| Patient characteristics | ||

| Patients included, n (%) | In total | 223 (100) |

| Men | 122 (55) | |

| Women | 101 (45) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | |

| Patients excluded due to missing data, n/n total (%) | 4/227 (1.8) | |

| Age in years, mean (SD), median, range | 82 (7), 83, 64–98 | |

| Prescribed medications per patient, mean (SD), median, range | 9 (4), 9, 2–22 | |

| Number of diagnoses per patient, mean (SD), median, range | 17 (5), 16, 6–42 | |

| Diagnoses per patient (ten most prevalent diagnoses), n | Cerebrovascular event | 33 |

| Fracture | 23 | |

| Sepsis | 18 | |

| Fall | 17 | |

| Heart failure | 13 | |

| Pneumonia | 12 | |

| Polytrauma | 8 | |

| COPD exacerbation/Dyspnoea | 7 | |

| Pain | 6 | |

| Endocarditis | 4 | |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SD: standard deviation.

In total, clinical pharmacists intervened 480 times. Patients had a mean of 2.2 interventions (median: 2, range: 1–9). Based on descriptive comparisons, the number of interventions did not differ between men and women. Similarly, no difference was observed when the data were stratified by the referring provider.

According to the GSASA classification system, the most common categories of recorded problems were “Risk due to treatment” (227/480 or 47.3%), “Effect of the treatment” (85/480 or 17.7%) and “Indication not treated” (76/480 or 15.8%).

In parallel, the three most prevalent reasons for identified interventions were classified as “Choice of dose”, with 68 potentially too high and 35 potentially too low, totalling 103/480 (21.5%), “Other – omissions” (72/480 or 15.0%) and “Treatment without a clear indication” (64/480 or 13.3%). Details on the reasons for interventions are displayed in table 2.

Table 2Reasons for interventions recommended by the clinical pharmacists.

| Reasons for interventions | n (%) | |

| Choice of dose | Total | 103 (21.5) |

| Dose potentially too high | 68 (14.2) | |

| Dose potentially too low | 35 (7.3) | |

| Other – Omissions | 72 (15.0) | |

| Treatment without a clear indication | 64 (13.3) | |

| (Drug-drug) interactions | 44 (9.2) | |

| Non-conformity with guidelines / potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) | 40 (8.3) | |

| Incomplete patient documentation | 38 (7.9) | |

| (Potential) adverse event | 29 (6.0) | |

| Unsuitable route/form of administration | 21 (4.4) | |

| Duplication | 13 (2.7) | |

| Contraindication | 9 (1.9) | |

| Inappropriate treatment duration | 9 (1.9) | |

| Inappropriate/missing monitoring | 8 (1.7) | |

| Insufficient knowledge of medical staff | 5 (1.0) | |

| Insufficient knowledge of the patient | 3 (0.6) | |

| Inappropriate timing or frequency of administration | 2 (0.4) | |

| Prescribed medication unavailable | 1 (0.2) | |

| Error in the medication use process | 1 (0.2) | |

| Other | 18 (3.8) | |

| Total interventions | 480 (100) | |

The three intervention categories most commonly recommended by our clinical pharmacists were “Make dose adjustment” (104/480 or 21.7%), “Discontinue treatment” (102/480 or 21.3%) and “Start or restart medication” (79/480 or 16.5%). More intervention categories and their acceptance rates by prescribing physicians are presented in table 3. The recommended interventions with the highest rates of acceptance by physicians were “Optimise administration modality” (21/27 or 77.8%), “Substitute or exchange medication” (53/75 or 70.7%) and “Counsel or train patient” (5/8 or 62.5%), although this was a rare recommendation. Physicians’ lowest rate of acceptance was for “Start or restart medication” recommendations (17/79 or 21.5%). The recommended interventions which most frequently needed clarification and a decision from a senior physician or were referred to the patient’s primary care physician were “Clarification in the medical history” (39/53 or 73.6%) and “Change route of administration” (2/3 or 66.7%), although this was rarely an issue.

Table 3Characteristics, frequency and acceptance rates of interventions recommended by clinical pharmacists during the PharmVisit pilot study.

| Interventions recommended | Prevalence | Physician response to recommended intervention | ||

| Accepted | Referred | Rejected | ||

| Make dose adjustment, n (%) | 104 (21.7) | 62 (59.6) | 26 (25.0) | 16 (15.4) |

| Discontinue treatment, n (%) | 102 (21.3) | 63 (61.8) | 34 (33.3) | 5 (4.9) |

| Start or restart medication, n (%) | 79 (16.5) | 33 (41.8) | 29 (36.7) | 17 (21.5) |

| Substitute or exchange medication, n (%) | 75 (15.6) | 53 (70.7) | 10 (13.3) | 12 (16.0) |

| Clarification in the medical history, n (%) | 53 (11.0) | 9 (17.0) | 39 (73.6) | 5 (9.4) |

| Optimise administration modality, n (%) | 27 (5.6) | 21 (77.8) | 2 (7.4) | 4 (14.8) |

| Monitor therapy, n (%) | 19 (4.0) | 10 (52.6) | 6 (31.6) | 3 (15.8) |

| Counsel or train patient, n (%) | 8 (1.7) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Inform healthcare professionals, n (%) | 7 (1.5) | 2 (28.6) | 4 (57.1) | 1 (14.3) |

| Change route of administration, n (%) | 3 (0.6) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Make pharmacovigilance notification, n (%) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other, n (%) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) |

| Total, n (%) | 480 (100) | 260 (54.2) | 156 (32.5) | 64 (13.3) |

Based on the ATC’s first-level codes, the medication groups most often addressed by PharmVisit’s clinical pharmacists covered the following organ systems: A = alimentary tract and metabolism (70/480 or 14.6%), N = nervous system (68/480 or 14.2%) and C = cardiovascular system (36/480 or 7.5%). Other first-level codes were far less frequently involved in the issues raised by clinical pharmacists; they are available in appendix 3.

Clinical pharmacists made different interventions for different classes of drugs at ATC level 3 (see appendix 2 for more details). For acid-related drugs (A02), which were mainly proton pump inhibitors, pharmacists most often found that the drug was not indicated (n = 15 or 37%) or prescribed at too high a dose (n = 9 or 22%). For drugs used for diabetes (A10), pharmacists often found that treatments were missing (n = 9 or 38%). For analgesics (N02), pharmacists often found that doses were too high (n = 14 or 32%) or too low (n = 6 or 14%), or that they were a potentially inappropriate medication (n = 6 or 14%).

The PharmVisit study piloted and successfully implemented an interprofessional ward round process to improve medication safety among older adult patients in an acute geriatric ward at the University Hospital of Bern. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study in Switzerland to specifically explore clinical pharmacy services within the scope of daily ward rounds for such an older adult population.

Because of their multimorbidity, polypharmacy and frailty, older adult patients are at an elevated risk of medication-related problems [12]. Although a recent study in the USA suggested that geriatricians prescribed potentially inappropriate medications at lower rates than general internists [2], our clinical pharmacists nevertheless detected significant numbers of potential medication-related problems prescribed by the physicians collaborating in our project.

The average immediate acceptance rate of the interventions recommended by our clinical pharmacists during ward rounds was 54.2%, with 13.3% being rejected immediately and 32.5% being referred to senior physicians for a decision. This was slightly lower than in other interprofessional ward round projects executed in Switzerland: Reinau et al. reported an acceptance rate of 57.6% in 2019; however, that project addressed patients in a general internal medicine unit and patients’ ages were not reported [13]. A 2015 study conducted in an internal medicine unit at Geneva University Hospitals reported an initial acceptance rate of 84% of recommendations, although the final rate of changes implemented was 58%. Patients in that study had a mean age of 68 ± 16 years (compared to our population’s average of 82 ± 7 years), with greater polypharmacy (mean of 10.6 ± 4.0 medications per patient) than in our study (9 ± 4 medications).

Diverging recommendation acceptance rates might be explained by the different populations and settings in these studies. Our clinical ward rounds are also primarily attended by assistant physicians at the beginning of their clinical careers and with less clinical experience. This might explain why 32.5% of the interventions recommended did not receive an immediate decision during ward rounds but were referred to senior attending physicians for clarification and a decision or to the patient’s primary care provider for a discharge letter. Decision-making and therapy adjustments might also have been made more difficult by shorter hospital lengths of stay and in cases of incomplete anamnestic medication information.

Medication reconciliation – the process of “creating the most accurate list possible of all the medications a patient is taking and comparing that list against the physician’s admission, transfer, and/or discharge orders with the goal of providing correct medications to the patient at all transition points within the hospital” [14] – is not yet performed systematically at the University Hospital of Bern. Before being admitted to the acute geriatric ward, patients go through at least one transition of care, and the involvement of other medical specialties during their stay can create additional interfaces, potentially leading to medication misinformation [15]. A study from the University Hospital of Basel demonstrated that combining medication reconciliation with interprofessional ward rounds accompanied by clinical pharmacists could significantly increase the detection of medication-related problems [16]. Therefore, expanding clinical pharmacy services to include medication reconciliation might improve the pertinence of any interventions recommended. This could optimise discharge processes for physicians, making prescribing more efficient and less error-prone [17].

The most common reasons for the interventions recommended by pharmacists were the need for dose adjustments (21.7%) and medication omissions (15.0%). While the acceptance rate for dose adjustments was above average, at almost 60%, the immediate initiation or re-initiation of a medication was only accepted in 40% of cases.

Reinau et al. also reported dosing to be the most frequently addressed issue (24.0%) in ward rounds, comparable to our rate of 21.7% [13]. Guignard et al. reported that overdosage was identified in 16% of interventions, and subtherapeutic dosages were identified in another 8%, also adding up to 24% [6].

It is possible that pharmaceutical expertise is more developed and/or better accepted in certain clinical specialties. Increasing the participation of clinical pharmacists in routine ward rounds might improve levels of collaboration. We plan, therefore, to conduct a survey that will help to improve the acceptance and efficacy of PharmVisit processes as they transition to a routine part of clinical practice in our hospital.

The most commonly prescribed drug classes for elderly patients in Switzerland, as detailed in the 2017 Helsana Arzneimittelreport, were pain medication, proton-pump inhibitors and psycholeptics [18]. These drugs, plus laxatives and drugs for obstructive airway diseases, were also among the most common in our recommendations. The potential for preventing harm, specifically harm caused by pain medication (including analgesics, opioids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), hypnotics and sedatives, was also highlighted in a recent publication by the World Health Organization. Its report also pointed out the vulnerabilities of patients aged 80 or older [19]. These findings might help to prioritise the patients most at risk and focus on especially harmful medications in case of staff shortages or limited resources in general.

While we did not measure our study’s financial impact, a recent publication by Geneva University Hospitals detailed the return on investment of conducting ward rounds accompanied by clinical pharmacists. It found that inadequate dosing can cause mean extra costs of EUR 772 per medication-related problem [20]. In the present pilot study, the most frequent clinical pharmacist recommendation also addressed inadequate dosing, suggesting that the PharmVisit process could also be cost-effective.

Deprescribing is generally defined as “a systematic process of drug discontinuation, tapering or even substitution of inappropriate medications, supervised by a health care professional, with the goal of managing polypharmacy and improving outcomes” [21]. It can also contribute to safer and less costly medication therapies [22, 23]. In the present study, discontinuing a medication made up 21.3% of our recommendations, similar to the prevalence of 23.5% reported by Reinau et al. [13], and it was the second most frequently accepted recommendation, with a rate of 61.8%, well above our mean rate overall. Based on a study in a primary care setting, there is even potential to improve this rate if interprofessional collaboration for medication reviews and deprescribing is ongoing and encompasses, among other things, team-based training [24]. Within the scope of the PharmVisit project, clinical pharmacists have already started giving regular physician education sessions, emphasising the findings from the ward round project.

This quality improvement study had some limitations. Due to limited staffing, our clinical pharmacists could only accompany ward rounds once per week and attend to a limited number of patients at the University Hospital of Bern’s Department of Geriatrics. Due to those patients’ lengths of stay, often lasting one to two weeks, 52 patients were present for more than one interprofessional ward round, potentially limiting the number of recommended interventions in the scope of follow-up visits. Due to the regular rotation of assistant physicians in a teaching hospital, some of the interventions recommended may have been redundant, and the learning curve of this constantly changing team may have been limited. However, this might make the contribution of clinical pharmacists all the more meaningful. We have also tried to counteract these issues by integrating clinical pharmacists into physician teaching sessions.

Recommended interventions by clinical pharmacists are based on a medication Type 2b review. While data exist that inpatient medication reviews can reduce hospital readmissions and emergency department visits, they have little to no effect on mortality and an uncertain effect on quality of life [25]. While the clinical pharmacists were trained for PharmVisit by the same senior pharmacist and used the same checklist as a basis, inter-rater reliability in performing medication reviews was not measured and so might have influenced the recommendations made by clinical pharmacists, depending on the professional attending the ward rounds.

The Swiss Association of Public Health Administration and Hospital Pharmacists (GSASA) classification system has no categories for detailing the reasons for rejections of pharmacists’ recommendations. In addition, decisions on recommendations referred to senior physicians or the primary care providers were not necessarily recorded in the electronic patient record. Therefore, this information is missing in the data. An expansion of the GSASA classification system and an extended follow-up period should be considered in future studies.

While our study’s generalisability may be limited, due to its single-site design, other projects in Switzerland involving clinical pharmacists have shown comparable outcomes [6, 12, 15].

The PharmVisit process is now being implemented in regular daily practice and extended to more sectors of the Department of Geriatrics. Additionally, we are planning to focus ward rounds on thematic issues commonly raised during the pilot phase, for example, medication to relieve chronic non-cancer pain. We are also considering earlier medication reconciliations once a unit transfer decision has been made, predominantly from general internal medicine to geriatrics.

Our project emphasised how including clinical pharmacists in interprofessional ward round teams enabled a consideration of more viewpoints on the different aspects of a patient’s drug therapy. This led to a more critical debate on medication therapy decisions, as reflected in the favourable acceptance rates for interventions recommended by clinical pharmacists. With older adult patients at an elevated risk of medication-related problems, the high acceptance rates for deprescribing and dose adjustment recommendations could be especially significant when it comes to reducing potentially inappropriate medications and subsequent adverse events. We will strive to improve the effectiveness of the PharmVisit process by expanding this service to more patients, integrating medication reconciliations into initial internal hospital transfers and advancing interprofessional education.

Study data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

We sincerely thank Dr Franz Fäh, Dr Christof Stirnimann, Dr Dominic Bertschi, Dr Pascal Weber and the nursing team at the Inselspital-University Hospital of Bern’s Department of Geriatrics for hosting our clinical pharmacists on their ward for the PharmVisit pilot project. We thank PD Dr Daniel Meyer for providing the illustrations. We acknowledge the English-language copy-editing services provided by Darren Hart of "Publish or Perish".

Author contributions: Study concept: CM, AG, NS; Methodology: CM, PS, AG, NS, DM; Data collection: CM, AG, NS, DM, PS; Data curation: NS, AB; Data analysis: CM, PS, AG; Original draft preparation: PS, CM, AG; Review and editing: DM, NS, PS, AG, CM; Supervision: CM. All the authors have read and agreed to the final published version of this manuscript.

CMM’s endowed professorship is financed by the Swiss Pharmacists’ Association, pharmaSuisse. She has also obtained a grant for interprofessional collaboration from the Kollegium of Hausarztmedizin (KHM). NS is a smarter medicine grant holder.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. Mangoni AA, Jackson SH. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004 Jan;57(1):6–14.

2. Vandergrift JL, Weng W, Leff B, Gray BM. Geriatricians, general internists, and potentially inappropriate medications for a national sample of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2024 Jan;72(1):37–47.

3. Hanlon JT, Semla TP, Schmader KE. Alternative Medications for Medications in the Use of High-Risk Medications in the Elderly and Potentially Harmful Drug-Disease Interactions in the Elderly Quality Measures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015 Dec;63(12):e8–18.

4. Fishman L, Brühwiler L, Schwappach D. [Medication safety in Switzerland: where are we today?]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2018 Sep;61(9):1152–8.

5. Giannini O, Rizza N, Pironi M, Parlato S, Waldispühl Suter B, Borella P, et al. Prevalence, clinical relevance and predictive factors of medication discrepancies revealed by medication reconciliation at hospital admission: prospective study in a Swiss internal medicine ward. BMJ Open. 2019 May;9(5):e026259.

6. Guignard B, Bonnabry P, Perrier A, Dayer P, Desmeules J, Samer CF. Drug-related problems identification in general internal medicine: the impact and role of the clinical pharmacist and pharmacologist. Eur J Intern Med. 2015 Jul;26(6):399–406.

7. Blum MR, Sallevelt BT, Spinewine A, O’Mahony D, Moutzouri E, Feller M, et al. Optimizing Therapy to Prevent Avoidable Hospital Admissions in Multimorbid Older Adults (OPERAM): cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2021 Jul;374(1585):n1585.

8. Griese-Mammen N, Hersberger KE, Messerli M, Leikola S, Horvat N, van Mil JW, et al. PCNE definition of medication review: reaching agreement. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018 Oct;40(5):1199–208.

9. Hanlon JT, Schmader KE. The Medication Appropriateness Index: A Clinimetric Measure. Psychother Psychosom. 2022;91(2):78–83.

10. Maes KA, Tremp RM, Hersberger KE, Lampert ML; GSASA Working group on clinical pharmacy. Demonstrating the clinical pharmacist’s activity: validation of an intervention oriented classification system. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015 Dec;37(6):1162–71.

11. Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016 Dec;25(12):986–92.

12. Ye L, Yang-Huang J, Franse CB, Rukavina T, Vasiljev V, Mattace-Raso F, et al. Factors associated with polypharmacy and the high risk of medication-related problems among older community-dwelling adults in European countries: a longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr. 2022 Nov;22(1):841.

13. Reinau D, Furrer C, Stämpfli D, Bornand D, Meier CR. Evaluation of drug-related problems and subsequent clinical pharmacists’ interventions at a Swiss university hospital. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019 Dec;44(6):924–31.

14. Almanasreh E, Moles R, Chen TF. The medication reconciliation process and classification of discrepancies: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016 Sep;82(3):645–58.

15. Bourne RS, Jeffries M, Phipps DL, Jennings JK, Boxall E, Wilson F, et al. Understanding medication safety involving patient transfer from intensive care to hospital ward: a qualitative sociotechnical factor study. BMJ Open. 2023 May;13(5):e066757.

16. Studer H, Imfeld-Isenegger TL, Beeler PE, Ceppi MG, Rosen C, Bodmer M, et al. The impact of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation and interprofessional ward rounds on drug-related problems at hospital discharge. Int J Clin Pharm. 2023 Feb;45(1):117–25.

17. Botros S, Dunn J. Implementation and spread of a simple and effective way to improve the accuracy of medicines reconciliation on discharge: a hospital-based quality improvement project and success story. BMJ Open Qual. 2019 Aug;8(3):e000363.

18. Schneider R, Reinau D, Schwenkglenks M, Meier CR. Helsana Arzneimittelreport 2017. 2017. Available from: https://www.helsana.ch/ [last accessed: 30.05.2025].

19. The World Health Organization WHO. Global burden of preventable medication-related harm in health care: a systematic review. Geneva: 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/ [last accessed: 30.05.2025]

20. Jermini M, Fonzo-Christe C, Blondon K, Milaire C, Stirnemann J, Bonnabry P, et al. Financial impact of medication reviews by clinical pharmacists to reduce in-hospital adverse drug events: a return-on-investment analysis. Int J Clin Pharm. 2024 Apr;46(2):496–505.

21. Thompson W, Farrell B. Deprescribing: what is it and what does the evidence tell us? Can J Hosp Pharm. 2013 May;66(3):201–2.

22. Veronese N, Gallo U, Boccardi V, Demurtas J, Michielon A, Taci X, et al. Efficacy of deprescribing on health outcomes: an umbrella review of systematic reviews with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ageing Res Rev. 2024 Mar;95:102237.

23. Okafor CE, Keramat SA, Comans T, Page AT, Potter K, Hilmer SN, et al. Cost-Consequence Analysis of Deprescribing to Optimize Health Outcomes for Frail Older People: A Within-Trial Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2024 Mar;25(3):539–544.e2.

24. Radcliffe E, Servin R, Cox N, Lim S, Tan QY, Howard C, et al. What makes a multidisciplinary medication review and deprescribing intervention for older people work well in primary care? A realist review and synthesis. BMC Geriatr. 2023 Sep;23(1):591.

25. Bülow C, Clausen SS, Lundh A, Christensen M. Medication review in hospitalised patients to reduce morbidity and mortality. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023 Jan;1(1):CD008986.

The appendix is available in the pdf version of the article at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4351.