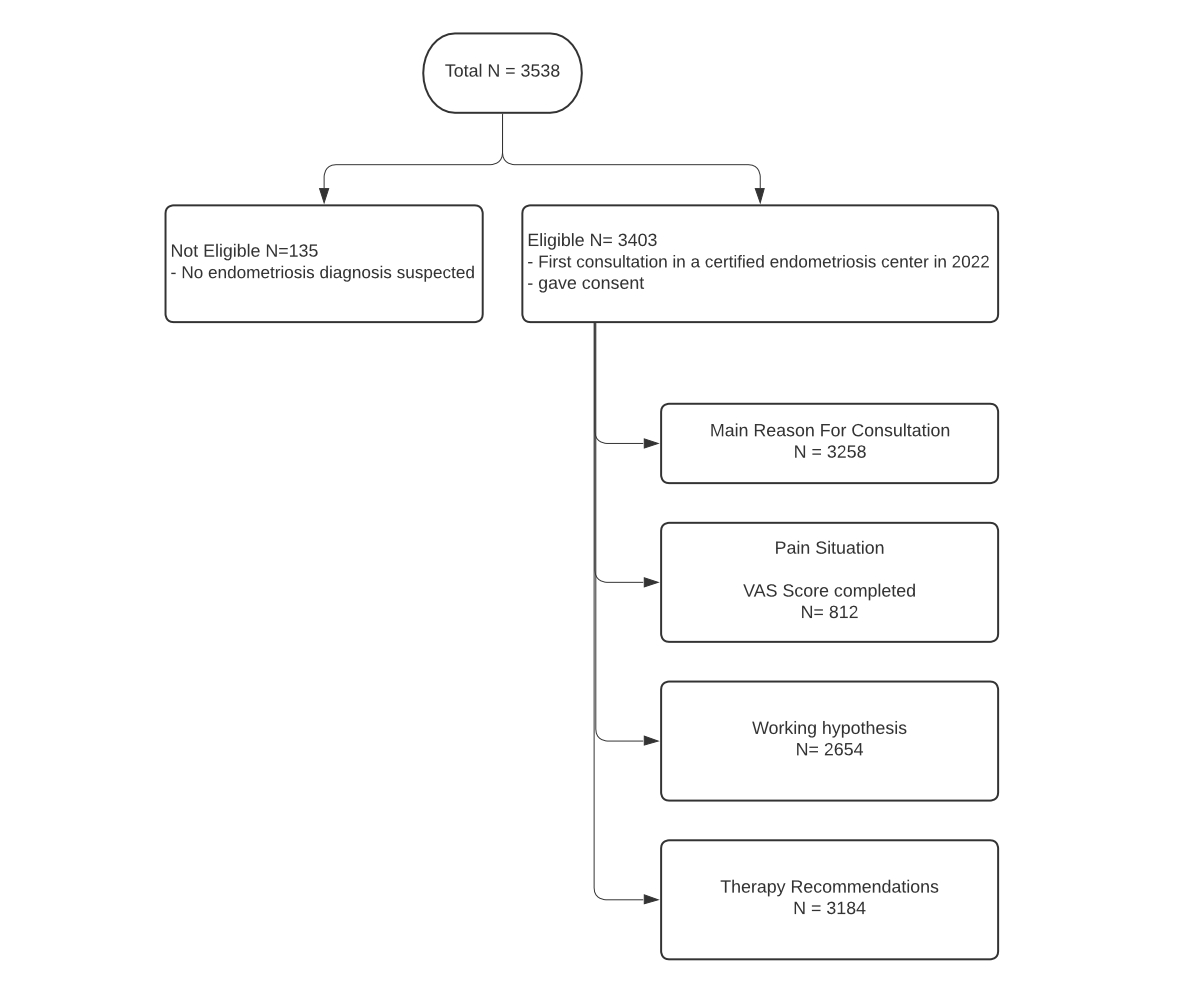

Figure 1Patient selection chart. VAS: visual analogue scale.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.3854

Endometriosis is a disease in which endometrium-like tissue grows outside the uterus. It is a very common disease, affecting approximately 10% of women of reproductive age [1]. In infertile women, the incidence of endometriosis is 30–50% [2]. It is a chronic, progressive disease with a high risk of recurrence [3].

In general, three forms of endometriosis are distinguished: ovarian endometriosis (endometrioma), peritoneal lesions and deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE). In addition, there is adenomyosis, a separate condition where endometrial glands grow into the myometrium [4]. Endometriosis can also occur outside the abdominal cavity and therefore cause a wide variety of symptoms. Typical symptoms of intra-abdominal endometriosis are dysmenorrhoea, dysuria, dyschezia, dyspareunia and sterility. However, a wide variety of symptoms such as chronic pelvic pain, chronic fatigue, diffuse visceral pain and psychosomatic disorders can also develop [5].

Women with endometriosis symptoms are usually in midlife, which usually is associated with work achievements, family milestones and social connections, patients often report a severe impact of their symptoms on major life decisions and attainment of goals [6], and show a 19% reduction in quality of life when compared with healthy people [7].

This is why in recent years the issue of endometriosis has appeared on the political stage, with large awareness campaigns and national programmes, and even the first dedicated national programme – in France – endorsed by President Macron in January 2022. In spring 2023, the Swiss Council of States (Ständerat) passed a postulate on women’s health, mentioning endometriosis explicitly (strategy for early detection of endometriosis) [8]. However, the motion to directly support endometriosis research was rejected in December 2023 [9].

To ensure a scientific approach to this disease, the Stiftung Endometriose Forschung (SEF, Endometriosis Research Foundation) and the European Endometriosis League (EEL) developed a certification process to allow major hospitals to serve as certified endometriosis centres. This system guarantees a structured setting offering high-quality care. Secondly, these structures make it possible to collect standardised data in the form of a nationwide databank.

The certified endometriosis centres in Switzerland united to form a Swiss Endometriosis Database group in 2021, under the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Endskopie (AGE, Swiss Working Group for Gynaecological Endoscopy) to unify data collection and strengthen future studies through expanded databases.

As 10% of women of reproductive age (12–50 years) are considered to be affected by endometriosis, according to the Federal Statistical Office (Bundesamt für Statistik [BFS]), around 145,000 women in Switzerland most likely had endometriosis in 2022 (BFS – ESPOP, n.d.). This shows that there is indeed an overall medical/social problem that needs to be addressed urgently.

Up to now, there has only been limited knowledge about endometriosis patients in Switzerland, their complaints and the treatment needed for these patients. To address this lack of fundamental knowledge, the present study aimed to survey and analyse the endometriosis symptoms and diagnoses of endometriosis patients in Switzerland in 2022 and to analyse the therapies that were prescribed. The study analysed the main reasons for seeking a first consultation as well as the individual pain situations, the working hypotheses (diagnoses) that were developed and the resulting therapy recommendations.

In this exploratory, retrospective multicentre cohort study, original data were collected prospectively as part of the certification process for each hospital. All patients who had their first consultation at a certified endometriosis centre in 2022 and gave their consent were selected for the study. The database includes data from 10 certified endometriosis centres in Switzerland, all of which use Adjumed Collect [11], an anonymous web-based input tool used to gather medical data for the SEF/EEL certification process.

The aim of the study was to understand the symptoms and endometriosis findings of Swiss endometriosis patients in 2022 and what therapies have been started. Therefore, the following endpoints were analysed:

Data were collected by questionnaires, which were filled out by the patient (VAS scores for defined symptoms) and the physician at each consultation (main reason for consultation, working hypothesis and recommended therapy). The questionnaires were completed before and during the anamnesis interview using a tablet or on paper, as part of the usual consultation.

Beyond the core data, the database contains information about infertility and possible past endometriosis surgeries, as well as information about the resulting working hypothesis established at the first visit and the recommendations subsequently decided upon. The women rated the severity of their symptoms during the previous four weeks using VAS scores, from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain). The VAS scores were divided into five categories: pain during period (dysmenorrhoea), non-cyclical pain, dyspareunia (pain during and after sexual intercourse), dyschezia and dysuria.

The main cohort includes all women who had their first consultation at a certified endometriosis centre in 2022 and who were diagnosed with endometriosis at the end of the consultation. They sought the centre’s help either on their own initiative or via referral.

Finally, symptoms and clinical parameters (VAS scores, main reason for consultation, working hypothesis/diagnosis, recommended therapy) were compared with each other.

The statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 25.0. Basic descriptive statistics were applied for both patient and clinical data analyses. Comparison of the symptoms and findings was conducted using cross tables (Chi square) and the ANOVA test. ANOVA tests were applied to analyse nominal factors with three or more outcome groups. Independences and continuity are given, normality and homogeneity were assumed due to the cohort, however not tested.

Visualisation of the findings was performed by R version 4.2.0 as well as Microsoft Excel. Results with a p-value <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The study was reviewed and approved by the local ethics committee of the canton of Bern (2024-01826).

From a total of 3538 consultations, 3403 met the selection criteria (figure 1).

Figure 1Patient selection chart. VAS: visual analogue scale.

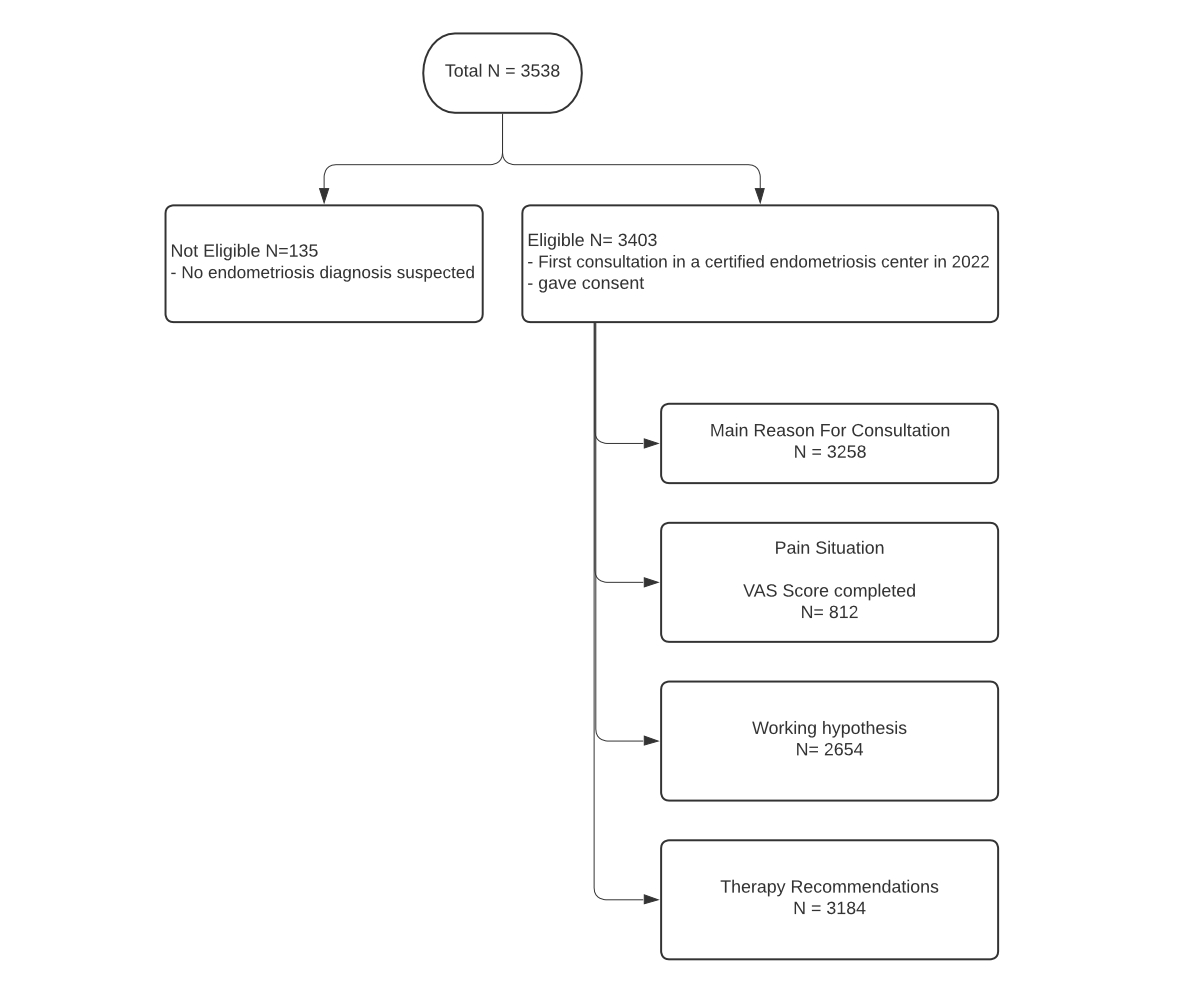

The median patient age was 33.0 years (11–66 years) at the time of the first consultation (figure 2).

Figure 2Patient characteristics. The graph shows the age distribution of all women who were analysed for this study.

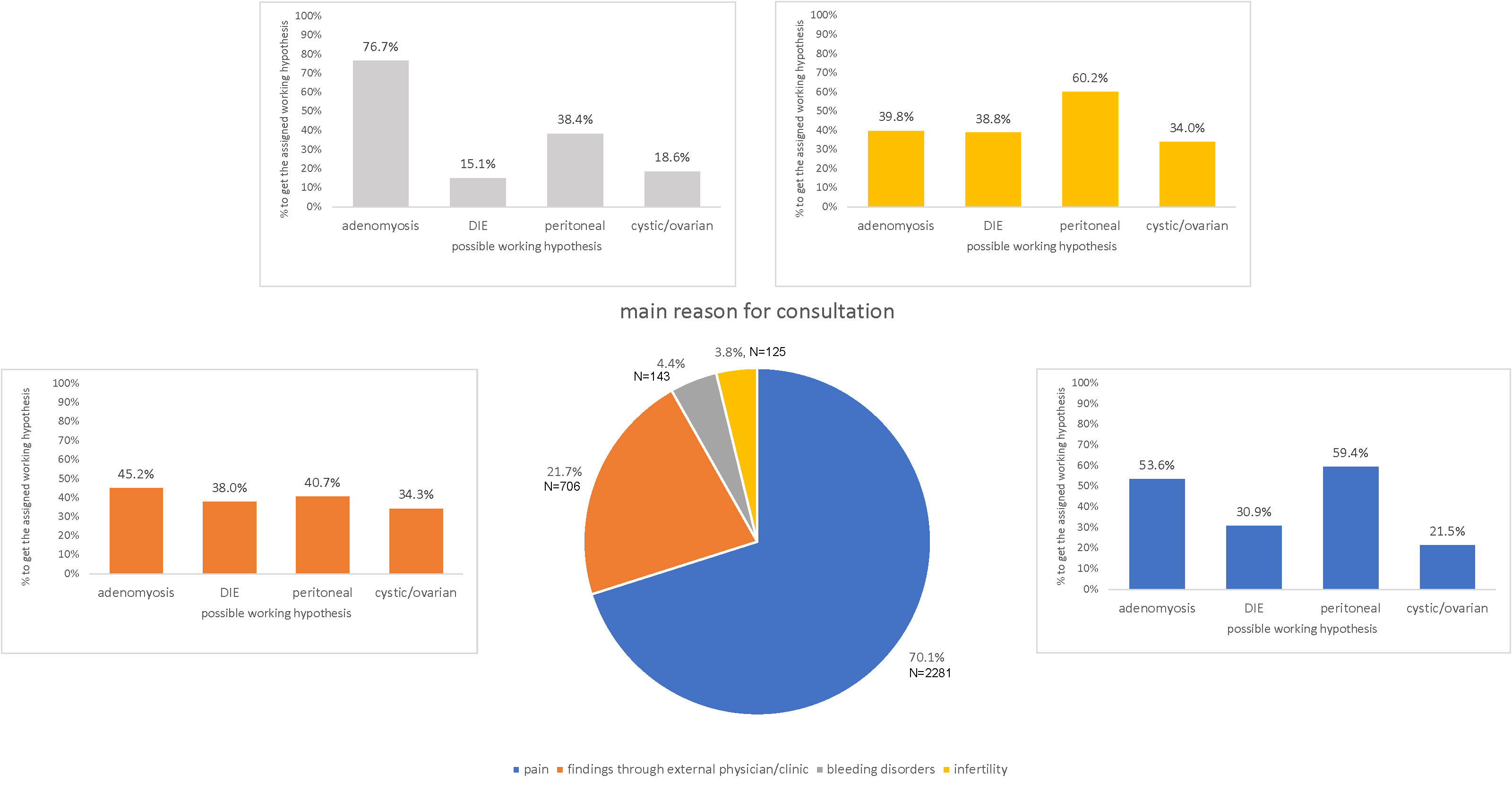

Pain was the most cited main reason for the doctor’s visit (n = 2281, 70.1%) followed by unclear findings from an external physician/clinic (n = 706, 21.7%), bleeding disorders (n = 143, 4.4%) and infertility (n = 125, 3.8%) (missing data in n = 148).

Of all women analysed in the context of this study, 319 (9.8%) had problems becoming pregnant for more than 12 consecutive months. In total, 854 (26.2%) women had already had one or more surgeries for endometriosis before their first consultation at a certified centre, with a range of one to eight surgeries. Most of the women who had undergone surgery (n = 794, 93.4%) had received a histologically confirmed diagnosis. From the total cohort, 619 (19.4%) patients had abdominal surgery independent of endometriosis; 75 (2.4%) women had had at least three or more previous surgeries.

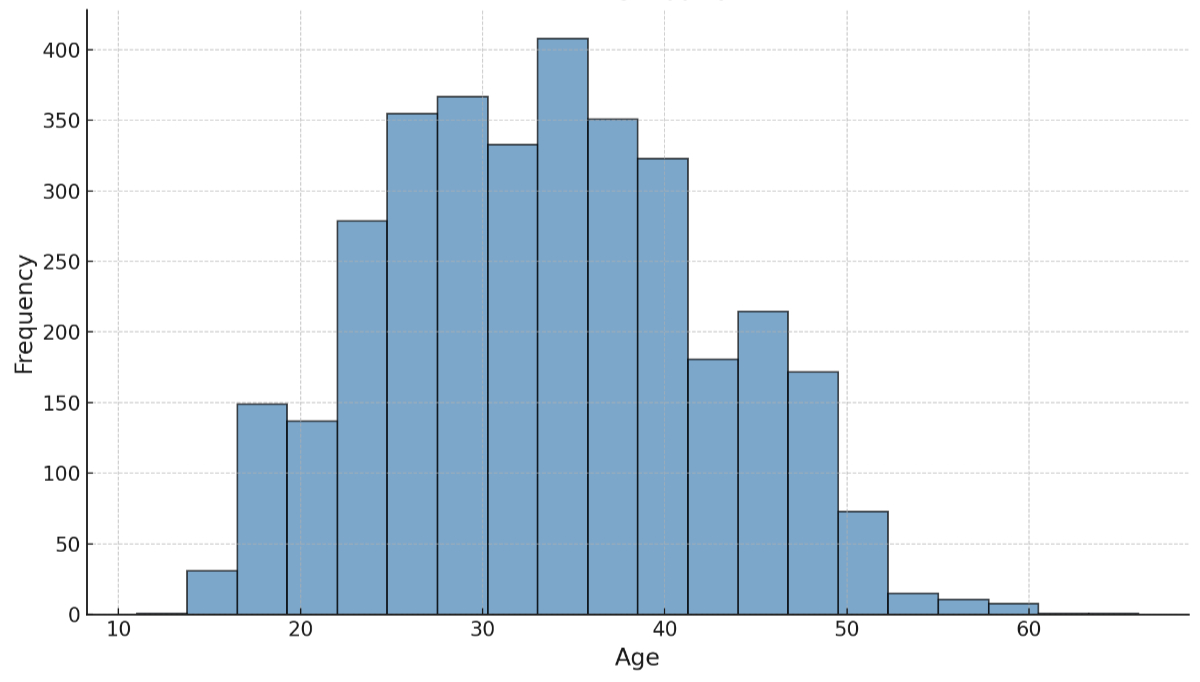

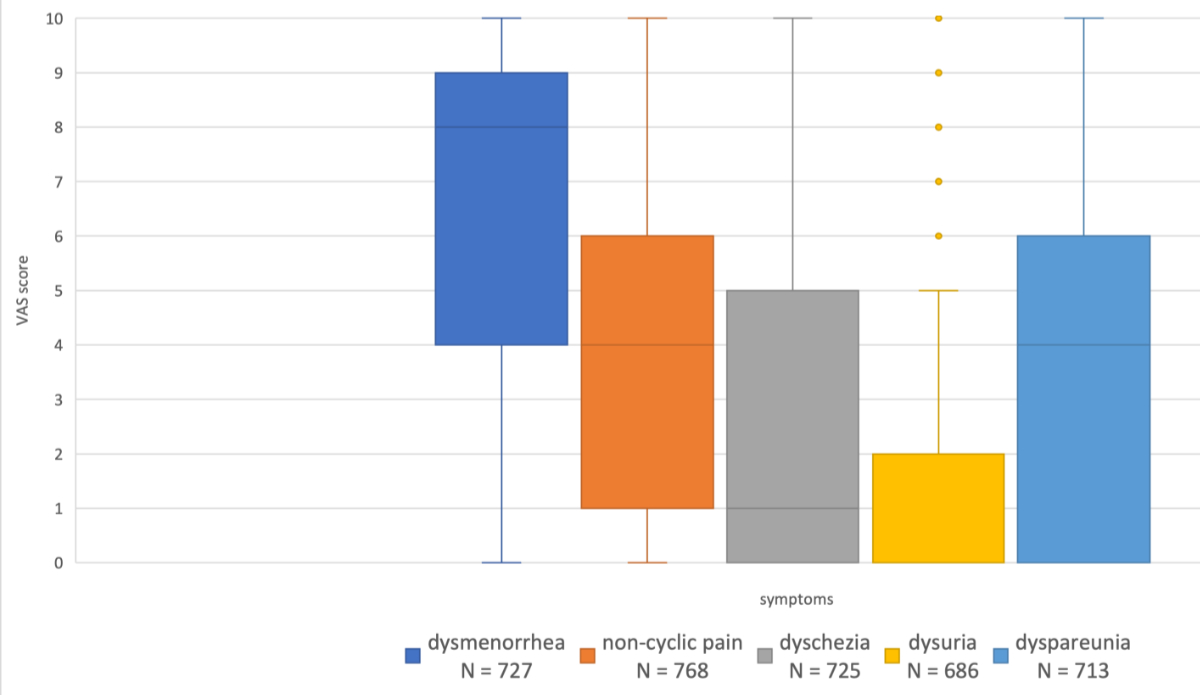

During the first consultation, 812 (25.5%) women documented their pain levels electronically, using a VAS score focusing on five aspects of endometriosis pain (pain during period, non-cyclical pain, dyspareunia, dyschezia, dysuria). By the time of the data collection, documentation of VAS scores was not mandatory and not linked to the database for all clients, which explains the low number of analysed VAS scores.

Around 581 (71.6%) of these women reported pain in general, and 727 of 812 (89.5%) women rated their dysmenorrhoea pain with a median VAS score of 8 (0–10), followed by non-cyclical pain with a median VAS score of 4 (0–10) and dyspareunia with a median of 4 (0–10). Dyschezia was rated with a median of 1 (0–10) and dysuria showed a median VAS score of 0 (0–10). The median VAS scores and ranges of all symptom groups are presented in figure 3.

Figure 3The plots show the median visual analogue scale (VAS) score for five types of pain (dysmenorrhoea, non-cyclical pain, dyschezia, dysuria and dyspareunia). Missing data: around 2676 (due to a non-mandatory data collection process).

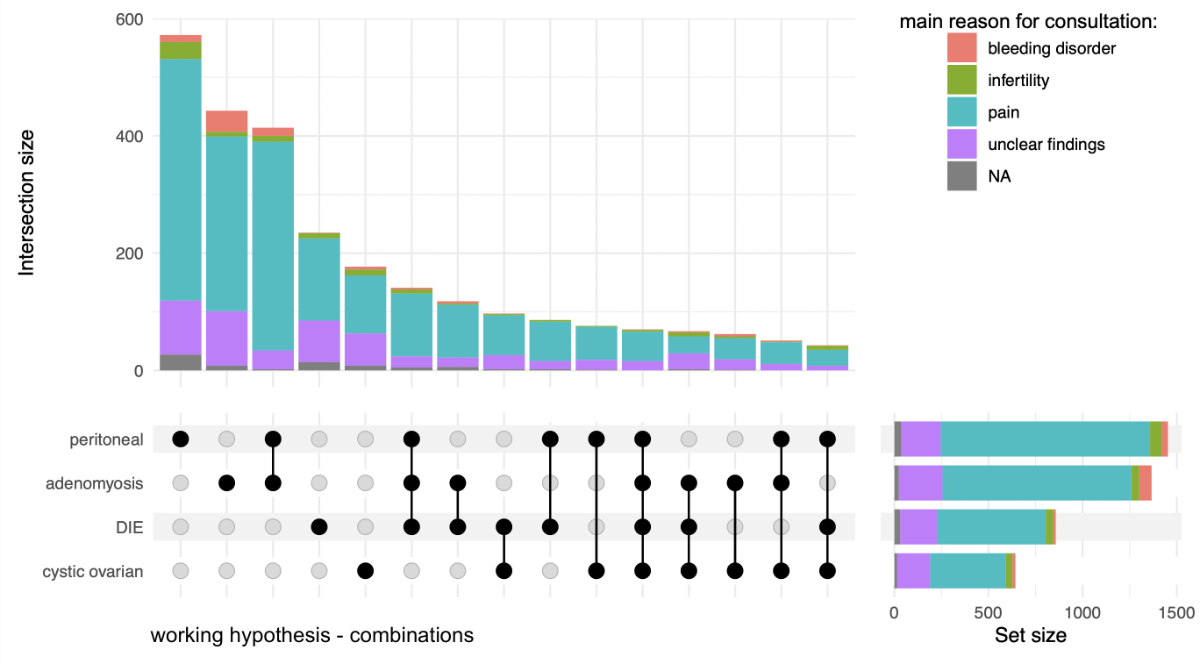

After clinical examination, 2654 (78%) patients were informed of one or more working hypotheses/diagnoses for the form of endometriosis, which was most often identified as peritoneal endometriosis n = 1453 (54.8%), followed by adenomyosis n = 1366 (51.5%), deep infiltrating endometriosis n = 857 (32.3%) and cystic/ovarian endometriosis n = 643 (24.2%). It is important to mention that a given woman can have more than one subtype of endometriosis and therefore is given more than one working hypothesis; this was the case for 1225 (46.2%) of the patients. A combination of all four subtypes was rare (n = 70, 2.6%); the most frequent combination was peritoneal endometriosis and adenomyosis (n = 414, 15.6%). The distribution of the different suspected endometriosis forms is presented in figure 4.

Figure 4Distribution of the different suspected endometriosis forms (working hypothesis) compared with the main reason of the first consultation. The black connections in the bottom left corner show all the various combinations of endometriosis forms that were found whereas the coloured bars above visualise the quantity of patients, subdivided by main reason for consultation. Missing data: patients without a main reason for consultation n = 148, patients without a working hypothesis n = 749, patients with a working hypothesis but without a main reason for consultation n = 93.

Significant differences (p <0.001) when comparing the main reason for consultation with the suspected endometriosis form are presented in figure 5.

Figure 5The pie chart presents the main reason for consultation. The bars present the distribution of suspected endometriosis subtypes within each group. DIE: deep infiltrating endometriosis. Missing data: patients without a main reason for consultation n = 148, patients without a working hypothesis n = 749.

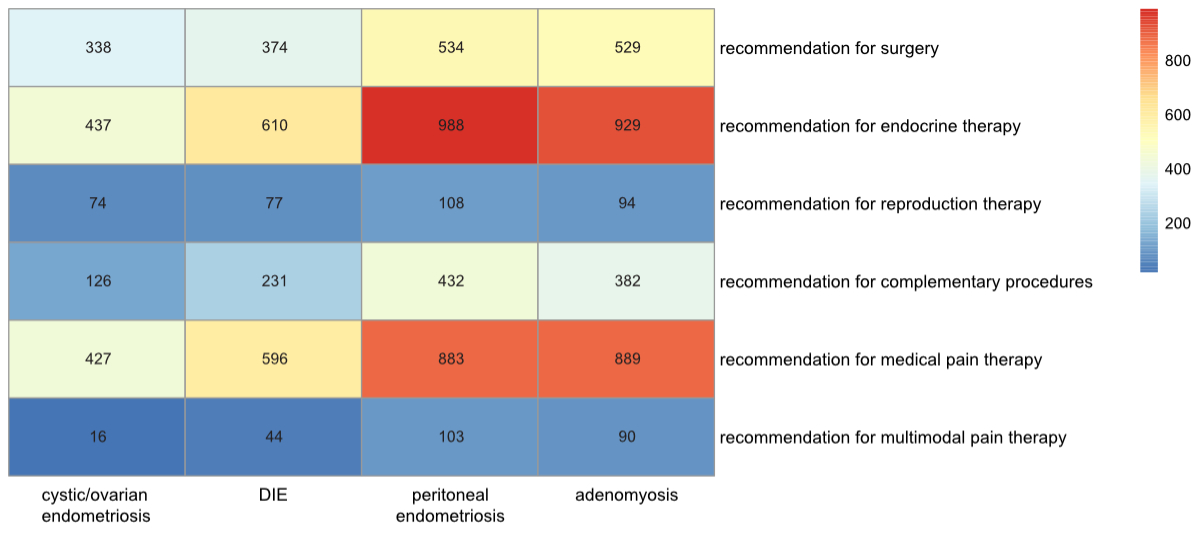

At the end of each woman’s first consultation, different recommendations were made. Each patient was given one or multiple recommendations for treatment. Endocrine therapy was the most common recommendation (n = 2063, 60.6%), followed by medical pain therapy (n = 1940, 57%), surgery (n = 1170, 34.4%), complementary medical procedures (n = 799, 23.5%), assisted reproductive therapy (n = 195, 5.7%) and multimodal pain therapy (n = 191, 5.6%). The combinations of recommendations are presented in figure 6.

Figure 6The heatmap visualises data about working hypotheses (cystic/ovarian, deep infiltrating endometriosis [DIE], peritoneal, adenomyosis) on the x-axis and therapy recommendations on the y-axis. The more common the specific combination, the redder the field. Missing data: patients without a working hypothesis n = 749, patients without a therapy recommendation n = 227.

For a deeper analysis of the different pain levels and types, the VAS scores were compared with the recommended therapies. This comparison is presented in table 1.

Table 1This table shows the mean VAS scores in relation to therapy recommendations. Missing data: patients without a therapy recommendation n = 227.

| Recommended therapy | VAS dysmenorrhoea (cyclical pain) | VAS non-cyclical pain | VAS dyschezia | VAS dysuria | VAS dyspareunia | |||||||||||

| Missing data: n = 2676 | Missing data: n = 2635 | Missing data: n = 2678 | Missing data: n = 2717 | Missing data: n = 2690 | ||||||||||||

| n | Mean (95% CI) | n | Mean (95% CI) | n | Mean (95% CI) | n | Mean (95% CI) | n | Mean (95% CI) | |||||||

| Surgery | No | 443 | 6.10 (5.80–6.41) | p = 0.007 | 481 | 3.91 (3.66–4.17) | p = 0.986 | 448 | 2.44 (2.17–2.70) | p = 0.622 | 420 | 1.28 (1.06–1.50) | p = 0.481 | 440 | 3.78 (3.49–4.06) | p = 0.667 |

| Yes | 269 | 6.77 (6.40–7.14) | 274 | 3.91 (3.54–4.27) | 265 | 2.55 (2.17–2.92) | 255 | 1.42 (1.10–1.73) | 260 | 3.67 (3.27–4.06) | ||||||

| Endocrine therapy | No | 230 | 6.50 (6.09–6.90) | p = 0.389 | 241 | 3.97 (3.59–4.34) | p = 0.672 | 235 | 2.33 (1.96–2.70) | p = 0.349 | 214 | 1.19 (0.88–1.50) | p = 0.303 | 223 | 3.65 (3.22–4.07) | p = 0.649 |

| Yes | 484 | 6.27 (5.98–6.57) | 515 | 3.87 (3.62–4.12) | 478 | 2.55 (2.28–2.81) | 461 | 1.40 (1.17–1.62) | 478 | 3.76 (3.48–4.04) | ||||||

| Reproductive therapy | No | 683 | 6.41 (6.18–6.65) | p = 0.040 | 727 | 3.91 (3.70–4.13) | p = 0.491 | 682 | 2.49 (2.27–2.71) | p = 0.377 | 649 | 1.32 (1.13–1.50) | p = 0.845 | 673 | 3.77 (3.53–4.00) | p = 0.065 |

| Yes | 29 | 5.17 (3.80–6.55) | 27 | 3.52 (2.24–4.80) | 29 | 2.00 (0.98–3.02) | 24 | 1.42 (0.49–2.34) | 27 | 2.63 (1.55–3.71) | ||||||

| Complementary procedures | No | 559 | 6.26 (5.99–6.53) | p = 0.129 | 593 | 3.79 (3.55–4.03) | p = 0.047 | 560 | 2.39 (2.15–2.63) | p = 0.142 | 536 | 1.33 (1.12–1.53) | p = 0.973 | 551 | 3.67 (3.41–3.94) | p = 0.422 |

| Yes | 154 | 6.70 (6.21–7.19) | 162 | 4.31 (3.87–4.74) | 152 | 2.78 (2.29–3.28) | 138 | 1.32 (0.90–1.73) | 149 | 3.91 (3.40–4.42) | ||||||

| Medicinal pain therapy | No | 255 | 5.54 (5.13–5.95) | p <0.001 | 268 | 3.47 (3.13–3.82) | p = 0.003 | 252 | 2.07 (1.73–2.41) | p = 0.008 | 240 | 1.32 (0.99–1.65) | p = 0.947 | 253 | 3.40 (3.00–3.80) | p = 0.042 |

| Yes | 457 | 6.79 (6.51–7.06) | 486 | 4.13 (3.87–4.39) | 459 | 2.68 (2.41–2.96) | 434 | 1.33 (1.11–1.55) | 446 | 3.90 (3.61–4.19) | ||||||

| Multimodal pain therapy | No | 658 | 6.30 (6.05–6.55) | p = 0.097 | 683 | 3.77 (3.54–3.99) | p <0.001 | 642 | 2.43 (2.20–2.66) | p = 0.159 | 608 | 1.22 (1.03–1.40) | p <0.001 | 363 | 3.58 (3.33–3.82) | p <0.001 |

| Yes | 53 | 7.06 (6.25–7.86) | 70 | 5.21 (4.63–5.80) | 68 | 2.96 (2.24–3.68) | 64 | 2.36 (1.63–3.09) | 62 | 5.23 (4.47–5.98) | ||||||

VAS: visual analogue scale.

Next, a comparison between the working hypothesis (diagnosis) and the recommended therapy was made in order to evaluate which endometriosis form resulted in which therapy. The findings are summarised in table 2.

Table 2The cross table shows significant correlations between the working hypotheses and recommended therapies. Missing data: patients without a working hypothesis n = 749, patients without a therapy recommendation n = 227.

| Therapy recommendations | Working hypothesis | |||||||||||

| Peritoneal | Cystic/ovarian | Deep infiltrating endometriosis | Adenomyosis | |||||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |||||

| Surgery Yes | 497 (41.6%) | 534 (36.8%) | p = 0.013 | 693 (34.5%) | 338 (52.7%) | p <0.001 | 657 (36.7%) | 374 (43.7%) | p <0.001 | 502 (39.1%) | 529 (38.8%) | p = 0.856 |

| Endocrine therapy Yes | 824 (68.9%) | 988 (68.0%) | p = 0.620 | 1375 (68.5%) | 437 (68.2%) | p = 0.886 | 1202 (67.0%) | 610 (71.4%) | p = 0.021 | 883 (68.8%) | 929 (68.0%) | p = 0.652 |

| Reproductive therapy Yes | 71 (6.0%) | 108 (7.4%) | p = 0.129 | 105 (5.2%) | 74 (11.6%) | p <0.001 | 102 (5.7%) | 77 (9.0%) | p = 0.001 | 85 (6.6%) | 94 (6.9%) | p = 0.797 |

| Complementary procedures Yes | 261 (21.9%) | 432 (29.8%) | p <0.001 | 567 (28.3%) | 126 (19.7%) | p <0.001 | 462 (25.8%) | 231 (27.1%) | p = 0.467 | 311 (24.3%) | 382 (28.0%) | p = 0.030 |

| Medical pain therapy Yes | 818 (68.6%) | 883 (60.9%) | p <0.001 | 1274 (63.6%) | 427 (66.7%) | p = 0.152 | 1105 (61.7%) | 596 (70.0%) | p <0.001 | 812 (63.4%) | 889 (65.2%) | p = 0.338 |

| Multimodal pain therapy Yes | 65 (5.5%) | 103 (7.1%) | p = 0.084 | 152 (7.6%) | 16 (2.5%) | p <0.001 | 124 (6.9%) | 44 (5.2%) | p = 0.081 | 78 (6.1%) | 90 (6.6%) | p = 0.592 |

In this large study, pain was by far the most frequently cited reason for a consultation at a certified endometriosis centre in Switzerland, even though pain is only one of a very heterogeneous array of symptoms of endometriosis [5]. Pain is clearly the overriding problem of patients with endometriosis. Taking a closer look at pain and the VAS scoring as an instrument to measure this individual symptom, our data show that approximately 71.5% of women who filled in the questionnaire experience pain in general. With a median of eight points out of a maximum of ten, the pain reported was severe [12].

A similar score was found by Missmer et al. With a mean score of 8.9 points on the severity scale, more than 50% of the affected women experienced severe pain daily. Furthermore, they showed that women with endometriosis described a negative impact on their professional and educational achievements, their social lives, relationships and general physical health due to their diagnosis [6].

Furthermore, according to Simoens at al., 56% of the women in their cohort, all diagnosed with endometriosis, live with a 19% reduction in their quality of life compared to a healthy person, based on an average loss of 0.8 quality-adjusted life years over the course of one year [7].

Data from the cohort attending an endometriosis centre for pain confirm the high levels of pain that these patients are dealing with: in 2022 alone, 2281 women experienced high levels of pain, while at the same time dealing with social activities, career and having a family. The negative impact of endometriosis is mostly driven by endometriosis-induced pain (Mabrouk et al., 2011), which is proven to have a big influence during this phase of life [14]. In a recently published study by Andres et al., it was shown that women with a VAS score of over seven have a significantly lower quality of life; this confirms that the high VAS scores alone are a sign of severe impact of the disease [15].

Looking at other symptoms, it was found that non-cyclical pain showed a rather low mean VAS score of four. This is possibly also due to the unclear definition of non-cyclical pain in the questionnaire (VAS scores are ideal for clear categories such as dysmenorrhoea but more difficult to use in pain such as chronic pain [12]). Dyschezia and dysuria showed surprisingly low mean VAS scores, which is in line with the results of [15], which show a mean VAS score for dysuria of 1.2 ± 2.7. Whether this is because they occur only rarely or they are masked by general pain could not be evaluated in this study.

The small percentage (3.8%) of women in this study whose main reason for consultation was infertility is very low, compared to the infertility rate in patients with endometriosis described in the current literature. The 9.8% rate of unachieved pregnancy in the previous 12 months at the time of consultation is also low. In the literature, around one third of the affected women experience infertility; which is almost twice the rate of non-affected women [5].

The low infertility rate in this study could be explained by the way endometriosis centres are structured in Switzerland: infertility centres are integrated in most endometriosis centres but have their own consultations. As a result, infertility patients might not have been enrolled in this study because they went directly to an infertility consultation.

In this study, three forms of endometriosis (ovarian endometriosis, peritoneal and deep infiltrating endometriosis) and also adenomyosis were differentiated based on clinical findings and imaging by an endometriosis specialist. It is important to note that these phenotypes are not mutually exclusive.

Determining the true prevalence of endometriosis and its phenotypes requires surgical visualisation, mostly done through laparoscopy, which makes research in this specific field extremely difficult [5]. Since the data analysed for this study contain only information from the first consultation, which does not include surgery, the endometriosis diagnosis of the patients is in most cases just a well-founded assumption, as only 26.6% of the included women had undergone endometriosis-specific surgery previously. It is of the utmost importance to understand that surgery, the standard diagnostic tool, is most often indicated only as a back-up treatment option and should be deployed judiciously for diagnostic reasons [16]. This is one of the most discussed reasons why research on the incidence of phenotypes of endometriosis is rare and why it is difficult to draw conclusions from such research. Finding a way to clinically diagnose endometriosis reliably is therefore more important than ever [17].

Individual therapy and therefore assigning different symptoms to a certain endometriosis phenotype is a present need and explains why, in this study, working hypotheses have been made on the basis of clinical findings and examination after the first consultation. Only a few other studies reported on the distribution of phenotypes, and most of them do so in a surgical setting. Von Theobald et al. assessed the prevalence of the different types of endometriosis in France and their results were slightly different to ours. Counting and analysing “organ-specific procedures” that were assigned to a type of endometriosis, they found that the ovarian procedure was the one most applied (40–60%) followed by the peritoneal procedure (20–30%) [18]. Nirgianakis et al. also analysed endometriosis recurrency surgeries and reported the most surgical procedures for ovarian endometriosis and endometriomas (n = 124/234), mentioning a detection bias at the same time. As the ovaries and ovarian endometriomas are easiest to detect non-surgically, through imaging via ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), they are automatically more likely to be examined and treated with surgery [19]. Another epidemiological study by Ávalos Marfil et al. from Spain showed similar results regarding types of endometriosis in a non-surgical setting. An evaluation of the incidence rate of the different endometriosis types in the 2014–2017 period showed again that tubo-ovarian endometriosis (35.2%) was the most often observed form, followed by uterine endometriosis (28.4%) [20]. Different findings were shown by Chen et al., who described that in 2008–2013 in Canada, 28.29% of patients with an endometriosis diagnosis who were admitted to a hospital, mostly for surgery, were diagnosed as having uterine endometriosis, followed by ovarian endometriosis (27.44%) [21].

All these different results do not neatly overlay with the results of the present study. This could be due to the fact that in our study, working hypotheses but not surgically confirmed diagnoses were analysed, as endometriosis and its phenotypes seems to appear in a wide variety and intensity of symptoms. Another reason might be that most of the compared results either did not cover the same information or were collected in a surgical setting, which creates differences in the selection of the included patients. And finally the patients in this study could be diagnosed with more than one endometriosis type as a working hypothesis, whereas in all the other literature, there was just one option retained. Therefore, these results should be viewed with a critical eye and interpreted with caution, as they describe only the situation as recorded in 2022 in Switzerland and do not allow for comparison with other literature. On the other hand, these descriptive findings are important as they present the clinically diagnosed endometriosis forms and they reflect the complexity of the situation, i.e. reflecting the everyday situation of both patients and physicians, and most importantly, presenting the endometriosis forms that require treatment and care.

For the patients seen at the certified centres, conservative treatment with endocrine and medical pain therapy was most often recommended. This is in line with the newly updated ESHRE (European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology) guidelines, showing that the primary treatment should be non-invasive [16].

The Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) also addresses the treatment of pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Putting disease treatment and management into focus, they discuss endometriosis as a primarily medical disease with surgical back-up treatment, because of its chronic characteristics and therefore the need for a long-term management plan. This is why patients should, as first-line therapy, be treated medically, reserving surgery for cases that do not respond to other treatment options [22].

In our study, 34.4% of the patients received a recommendation for surgery after the first consultation. These patients had significantly higher VAS scores for cyclical pain than the scores of those who did not receive a recommendation for surgery. However, we have no data on previous treatments; possibly many of these patients have already undergone first-line medical treatments. Patients with suspected cystic/ovarian or deep infiltrating endometriosis were significantly more likely to receive a treatment recommendation for surgery, whereas patients with suspected peritoneal endometriosis were less likely to receive a recommendation for surgery. However, the indication for surgery itself cannot be based solely on a pain score or a working hypothesis. In fact, there appear to be no clear criteria for surgery. Leonardi et al. wrote in a systematic review and meta-analysis that laparoscopic surgery may improve overall pain levels [23], while Bafort et al. reported in a systematic review being uncertain whether laparoscopic surgery reduces overall pain in patients with minimal to severe endometriosis [24]. Both agreed on the low to moderate quality of the data analysed. The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) therefore recommended – in their newest guidelines from 2022 – a shared decision-making approach regarding the choice of treatment [16].

It is interesting, though not surprising, to see that women with a treatment recommendation for complementary procedures, medical pain therapy and general multimodal therapy reported a significantly higher VAS Score for non-cyclical pain, so-called chronic pelvic pain, than those without such conditions. More and more often, the need for multimodal and complementary therapies is recognised and is identified in the treatment of endometriosis; it is an important part of the functioning of endometriosis centres to be able to provide these options to patients. In this cohort, a total of 876 women were recommended to have either complementary or multimodal treatment or both. This underlines the multimodal aspect of endometriosis patients’ needs and confirms the fact that endocrine or surgical treatment alone is not sufficient for these patients.

In reviewing the VAS scores for different symptoms that lead to therapy recommendations, the data analysed showed that higher dysmenorrhoea scores lead to the indication for surgery.

Every indication for surgery in endometriosis is personalised, balancing the burden of disease and the risks of surgery. No clear indication is given by the pain level or endometriosis type: it is always a multidimensional discussion made with the patient. Nonetheless, this analysis can help recognise that patients with higher pain levels might need more invasive treatment (surgery), just as patients with higher non-cyclical pain and multiple pain types (dyschezia, dyspareunia) need multiple treatment approaches (medical pain therapy, multimodal pain therapy) [25].

The same applies to the interpretation of the working hypothesis and the therapy recommendations. This decision is always multifactorial and individualised. Nevertheless, significant findings can be discussed and analysed:

Peritoneal endometriosis leads to significantly less surgery and to less multimodal treatment. Endocrine treatment is not indicated significantly more often, which is surprising, since this is usually the first indication for endocrine therapies [16]. It might be due to the fact that today many young women opt for treatments without hormones.

Ovarian endometriosis as a working hypothesis gets significantly more reproductive treatment and surgery; however, it does not lead to multimodal and medical treatment. This is possibly because endometriomas are well seen on ultrasound and physicians might be more prone to need of action. Also, medical treatment has a significant effect on the size of endometriomas, however they still stay present [26].

Women with deep infiltrating endometriosis seem to receive significantly more recommendations for surgery, endocrine and reproductive medicine as well as medical pain treatment than those without such a working hypothesis, meaning that more therapies all together may be needed to manage the disease. This underlines the need for interdisciplinary treatment modalities, which also is the approach of the certified centres, where different professions can contribute to the establishment of a patient’s treatment [27].

Contrary to what might have been expected, patients with suspected adenomyosis received hardly more therapy recommendations than those without adenomyosis. Only the recommendation for complementary procedures was significantly higher for these women.

This analysis helps in understanding indications, but it serves primarily to illustrate the complexity of the disease. It shows that good diagnosis of the different forms of endometriosis and the identification of multiple treatment options are needed to cover the different needs of patients and their endometriosis forms. With the implementation of multimodal treatment, this can be achieved.

Although the cohort is large, there were missing data (notably VAS scores) and the analysed parameters were determined primarily for centre certification and only secondarily for research. A selection bias could be present, resulting in underrepresentation of infertility patients, since they might be primarily treated in a reproductive medicine clinic outside of an endometriosis centre. Besides, all patients with endometriosis could be treated by their general gynaecologist outside of the centre setting.

Also “diagnosis” was framed as a working hypothesis, not a definitive diagnosis, which does not allow much comparison between other studies.

An information bias must be expected because of the multicentre nature of the study. Therefore, general conclusions must be made with care.

This multicentre study involved 8 of the 10 certified endometriosis centres in Switzerland and is the first ever description of the endometriosis-focused epidemiological situation in Switzerland, responding to an urgent need for better diagnosis and definition of optimal treatment. It supports diagnosis of endometriosis in a non-surgical setting, opens possibilities for more research and enables further exploitation of the national database.

It is replicable – and can be further refined – for subsequent years.

This is the first major study leveraging and analysing data from the Swiss Endometriosis Database. High VAS scores in dysmenorrhoea were found: this puts a spotlight on the suffering of patients with endometriosis seeking consultation at a certified endometriosis centre. It also emphasises the urgency and need for action: awareness building, diagnosis and treatment at all levels. The study shows that many women have multiple endometriosis forms and many have multiple treatment approaches, underlining the need for endometriosis units (private practice, clinic or centre) that have the experience and the structural setting to address these needs. This study provides the basis for further research needed to analyse the effect of the different treatment approaches.

We fully recognise the importance of transparency and data sharing in advancing scientific knowledge. However, in this case, we have chosen not to share the study data publicly. The data were collected from the first version of the database beginning in 2022 in a format that does not permit open-source publication or unrestricted analysis, primarily due to privacy and ethical considerations. Nonetheless, to promote openness, we will upload the study protocol to the Open Science Framework (OSF). Researchers interested in further details are welcome to contact us. Data access requests will be evaluated individually, with careful consideration of participant confidentiality and data security.

The authors would like to thank all patients for their consent to our accessing and using their anonymised healthcare data.

This study was not supported by any grants or industry contribution.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. Shafrir AL, Farland LV, Shah DK, Harris HR, Kvaskoff M, Zondervan K, et al. Risk for and consequences of endometriosis: A critical epidemiologic review. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018 Aug;51:1–15.

2. de Ziegler D, Borghese B, Chapron C. Endometriosis and infertility: pathophysiology and management. Lancet. 2010 Aug;376(9742):730–8.

3. Brosens I, Gordts S, Benagiano G. Endometriosis in adolescents is a hidden, progressive and severe disease that deserves attention, not just compassion. Hum Reprod. 2013 Aug;28(8):2026–31.

4. Bird CC, McElin TW, Manalo-Estrella P. The elusive adenomyosis of the uterus—revisited. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972 Mar;112(5):583–93.

5. Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Missmer SA. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar;382(13):1244–56.

6. Missmer SA, Tu F, Soliman AM, Chiuve S, Cross S, Eichner S, et al. Impact of endometriosis on women’s life decisions and goal attainment: a cross-sectional survey of members of an online patient community. BMJ Open. 2022 Apr;12(4):e052765.

7. Simoens S, Dunselman G, Dirksen C, Hummelshoj L, Bokor A, Brandes I, et al. The burden of endometriosis: costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum Reprod. 2012 May;27(5):1292–9.

8. Parlament. SDA KEYSTONE-SDA-ATS AG. Gezielte Forschung zu Frauenkrankheiten. 2023. Available from: https://www.parlament.ch/de/services/news/Seiten/2023/20230314115515858194158159038_bsd083.aspx

9. Ständerat. SDA KEYSTONE-SDA-ATS AG. Stärkere Förderung der Erforschung von Endometriose. 2023. Available from: https://www.parlament.ch/de/services/news/Seiten/2023/20231211164138528194158159038_bsd137.aspx

10. Bundesamt für Statistik (BFS). Demografische Bilanz nach Alter. 2023. Available from: https://www.pxweb.bfs.admin.ch/pxweb/de/px-x-0102020000_103/px-x-0102020000_103/px-x-0102020000_103.px/table/tableViewLayout2/

11. Adjumed Collect. Adjumed. 2025. Internet: https://adjumed.com/

12. Bourdel N, Alves J, Pickering G, Ramilo I, Roman H, Canis M. Systematic review of endometriosis pain assessment: how to choose a scale? Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(1):136–52.

13. Mabrouk M, Montanari G, Guerrini M, Villa G, Solfrini S, Vicenzi C, et al. Does laparoscopic management of deep infiltrating endometriosis improve quality of life? A prospective study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011 Nov;9(1):98.

14. Wüest A, Limacher JM, Dingeldein I, Siegenthaler F, Vaineau C, Wilhelm I, et al. Pain Levels of Women Diagnosed with Endometriosis: Is There a Difference in Younger Women? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2023 Apr;36(2):140–7.

15. Andres MP, Riccio LG, Abrao HM, Manzini MS, Braga L, Abrao MS. Visual Analogue Scale Cut-off Point of Seven Represents Poor Quality of Life in Patients with Endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2024 Apr;31(4:1146–50.

16. Becker CM, Bokor A, Heikinheimo O, Horne A, Jansen F, Kiesel L, et al.; ESHRE Endometriosis Guideline Group. ESHRE guideline: endometriosis. Hum Reprod Open. 2022 Feb;2022(2):hoac009.

17. Agarwal SK, Chapron C, Giudice LC, Laufer MR, Leyland N, Missmer SA, et al. Clinical diagnosis of endometriosis: a call to action. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Apr;220(4):354.e1–12.

18. von Theobald P, Cottenet J, Iacobelli S, Quantin C. Epidemiology of endometriosis in France: A large, nation-wide study based on hospital discharge data. BioMed Res Int. 2016;2016:3260952.

19. Nirgianakis K, Ma L, McKinnon B, Mueller MD. Recurrence patterns after surgery in patients with different endometriosis subtypes: A long‐term hospital‐based cohort study. J Clin Med. 2020 Feb;9(2):496.

20. Ávalos Marfil A, Barranco Castillo E, Martos García R, Mendoza Ladrón de Guevara N, Mazheika M. Epidemiology of endometriosis in spain and its autonomous communities: A large, nationwide study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jul;18(15):7861.

21. Chen I, Thavorn K, Yong PJ, Choudhry AJ, Allaire C. Hospital-Associated Cost of Endometriosis in Canada: A Population-Based Study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(5):1178–87.

22. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Treatment of pelvic pain associated with endometriosis: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2014 Apr;101(4):927–35.

23. M. Leonardi et al., “When to Do Surgery and When Not to Do Surgery for Endometriosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Feb. 01, 2020, Elsevier B.V. doi: .

24. Bafort C, Beebeejaun Y, Tomassetti C, Bosteels J, Duffy JM. Laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Oct;10(10):CD011031.

25. Comptour A, Pereira B, Lambert C, Chauvet P, Grémeau AS, Pouly JL, et al. Identification of Predictive Factors in Endometriosis for Improvement in Patient Quality of Life. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(3):712–20.

26. Thiel PS, Donders F, Kobylianskii A, Maheux-Lacroix S, Matelski J, Walsh C, et al. The Effect of Hormonal Treatment on Ovarian Endometriomas: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2024 Apr;31(4):273–9.

27. Meinhold-Heerlein I, Zeppernick M, Wölfler MM, Janschek E, Bornemann S, Holtmann L, et al.; AG QS Endo of the Stiftung Endometrioseforschung (SEF). QS ENDO Pilot - A Study by the Stiftung Endometrioseforschung (SEF) on the Quality of Care Provided to Patients with Endometriosis in Certified Endometriosis Centers in the DACH Region. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2023 May;83(7):835–42.