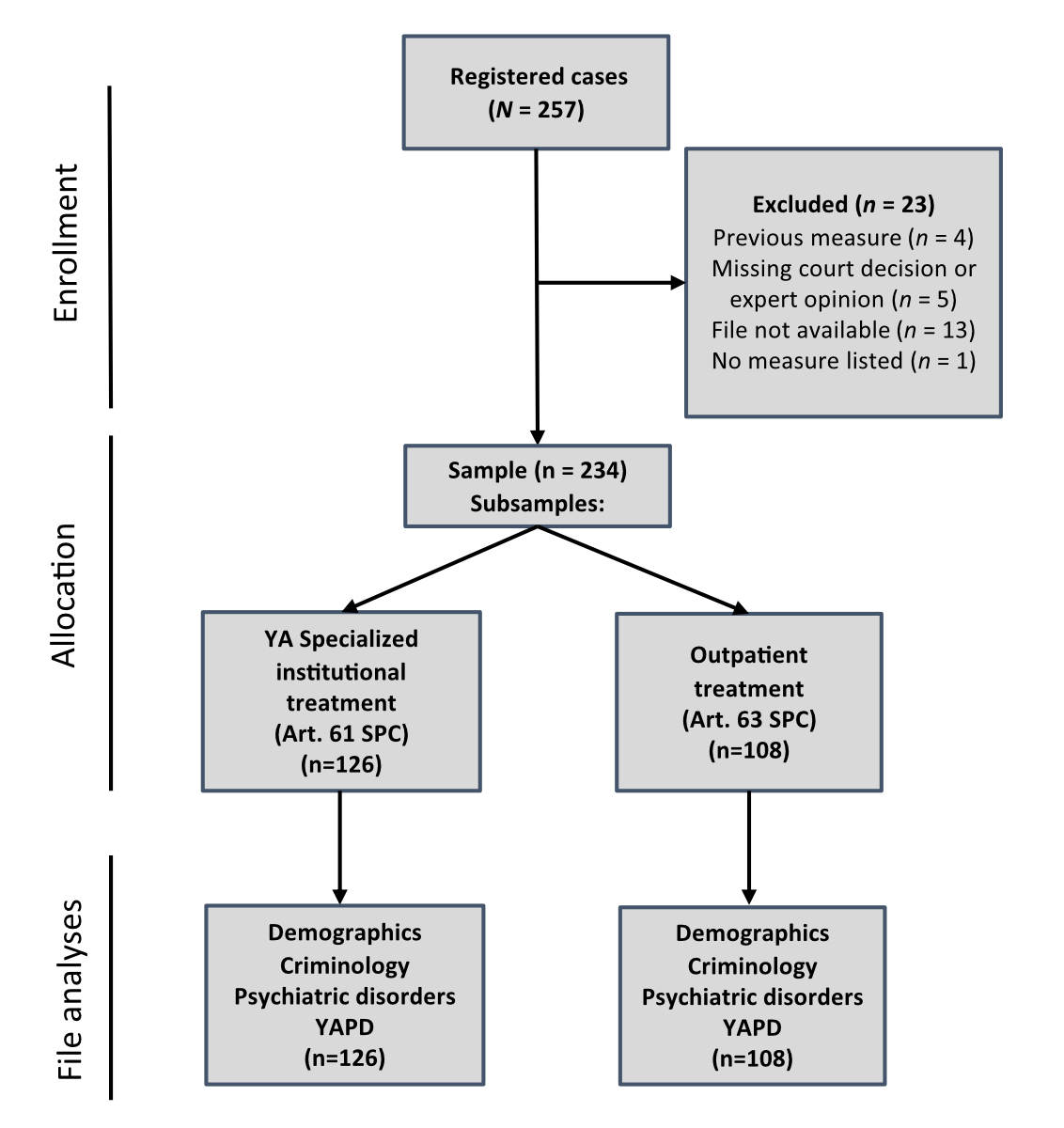

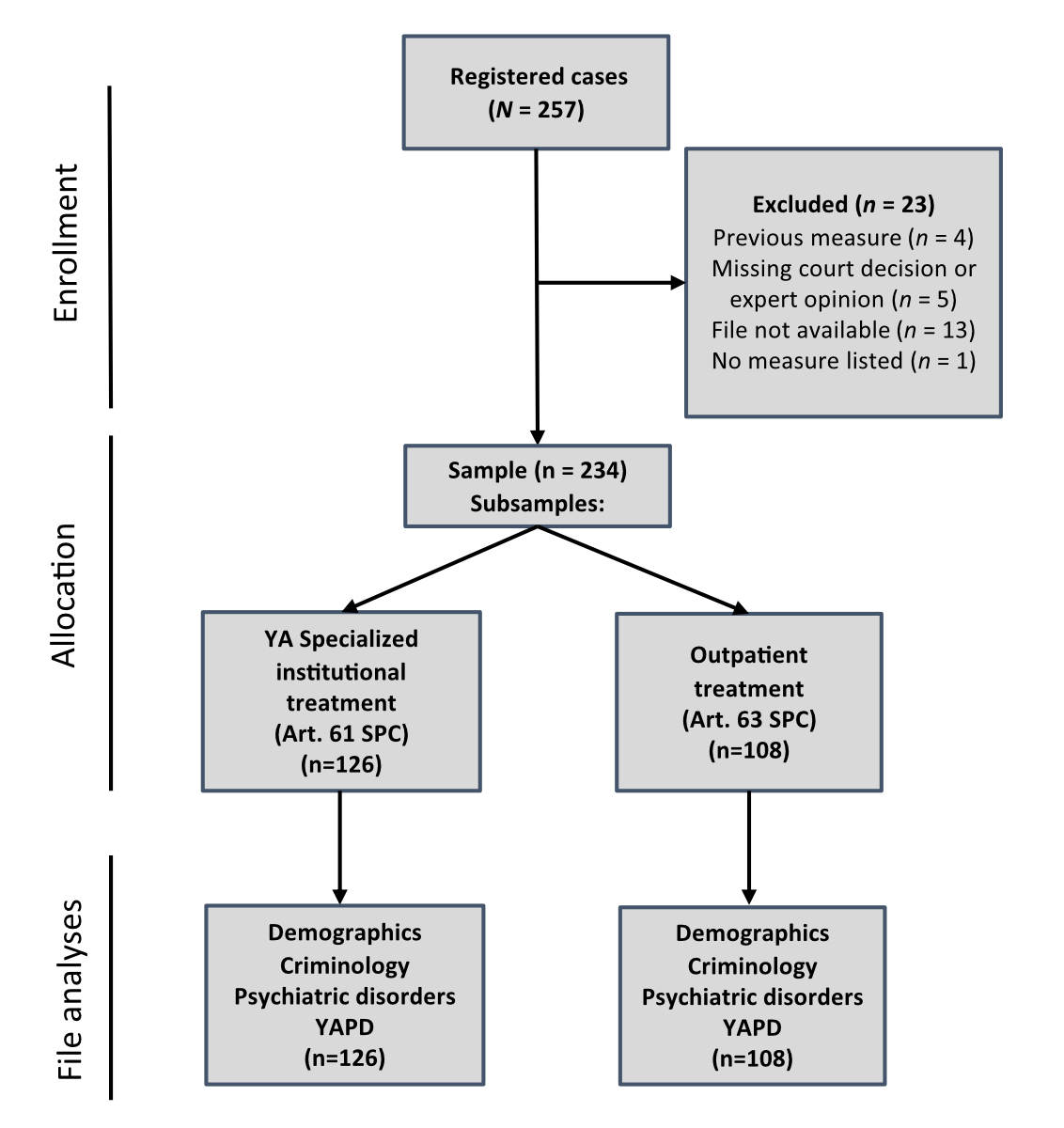

Figure 1Flowchart. SPC: Swiss Penal Code; YA: young adult; YAPD: young adult personality development.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.3793

In most countries, including Switzerland, the age of majority is set at 18 years. It is also at this age when many criminal laws for minor offenders cease to be applicable and “ordinary” criminal codes become the sentencing avenue for young adults. Although a fixed age of majority furthers legal certainty, this approach does not account for the different ways and timeframes in which young people mature and develop [1]. Criminal responsibility does not simply depend on a biological age but rather results from psychosocial and cognitive abilities that emerge during adolescence and early adulthood [1]. Maturity levels may vary considerably between same-age individuals [2]. As a consequence, some countries allow young adults to be treated as juveniles [1], whereas others allow juveniles to be treated as adults, particularly when they have committed purportedly “adult crimes” [3]. To assist the judge’s decision-making, forensic mental health experts worldwide are increasingly challenged to evaluate (im)maturity in adolescents and young adults.

Psychosocial maturity can be defined as the general level of an individual’s socioemotional competence and adaptive functioning in the society he or she lives [4]. Havighurst [5] suggested different developmental tasks in specific lifespan periods including childhood, adolescence, adulthood and older ages. According to his theory, all individuals from infancy to old age progress through a series of developmental stages, each comprising a series of developmental tasks. Adolescence can be seen as a critical period in which individuals typically need to build wholesome attitudes towards self and towards their cultural identity, and they need to build relationships with other people of different cultures and sexes [6]. If individuals fail in such developmental tasks in adolescence, they may be at particular risk for deviant social behaviours.

Steinberg and Cauffman [7] suggested a model of psychosocial maturity with three facets that are of particular interest in the context of antisocial behaviours, namely “temperance” (the ability to control impulses, including aggressive impulses), “perspective” (the ability to consider other points of view, including those that take into account longer-term consequences or that take the vantage point of others) and “responsibility” (the ability to take personal responsibility for one’s behaviour and resist the coercive influences of others). Using longitudinal self-reported data, the research group of Monahan et al. [8–10] found strong support of this model of psychosocial maturity and its relationship to criminal behaviours: Following a sample of initially 14 to 17-year-old male adolescents from the Pathways to Desistance study (all the adolescents were charged with criminal offences), the authors found a normative growth of psychosocial maturity over time with a significant increase during adolescence and a reduced increase during young adulthood. But even at the age of 25, the participants were found to still be developing [9]. Desisters from crime showed higher increases in psychosocial maturity compared to criminal persisters [9]. Further longitudinal studies confirmed psychosocial maturity deficits as predictive of future criminal offences [11, 12]. These observations cohered with findings from neurophysiology which show ongoing brain development processes up to the age of 25 years that are linked to psychosocial maturity (e.g. impulse control, executive functions) and criminal behaviours [13].

Given these findings, there is good reason to treat young adults differently in criminal law. In Switzerland, individuals aged 18 to 25 years who have committed a serious crime and were diagnosed with a severe disturbance of personality (based on a psychiatric-psychological expert opinion) can be assigned to a specific educational measure for young adults (Art. 61 of the Swiss Penal Code [SPC]; duration max. 4 years with a mandatory end if the individual reaches age 30). Four specialised institutional treatment centres for young adults exist and offer socio-pedagogical, educational, vocational, medical and psychotherapeutic services for residents. Most of the measures begin in a closed setting, and the young people are gradually given more freedom, depending on their progress. In the last 20 years, there has been a constant decrease, both in absolute numbers and in relative terms, in the number of young adults for whom this measure has been ordered vs those with other therapeutic measures [14]. It is not entirely certain what factors are responsible for this decline, but it may have been influenced by lower rates of psychiatric expert opinions of younger compared to older adult offenders [14], the diagnostic uncertainty in assessing maturity [3, 15] and the exclusion of psychologists for forensic expert opinions on young adults [16, 17]. Since psychosocial immaturity cannot be diagnosed in the same way as psychiatric disorders, which are based on standardised diagnostic criteria in the ICD-11 or DSM-5, forensic assessments remain mostly unguided and vulnerable to expert bias [3].

Reviewing the existing literature, Urwyler, Sidler and Aebi [15] recently suggested a multidimensional approach to assessing severe personality development disorder in order to decide on a measure for young adults according to SPC Article 61. The Young Adult Personality Development (YAPD) instrument is based on the principles of structured professional judgement (SPJ) and offers forensic experts a guided checklist to identify personality development disorder. The YAPD includes 3 items related to environmental risk factors, 2 items related to pathology risk factors and 10 items related to specific developmental tasks (see appendix table S1). In an additional step, criminal relevance and the presence of a severe personality development disorder should be estimated.

The present study aimed to analyse the reliability and concurrent validity of the YAPD dimensions based on juridical files/psychiatric expert opinions of young adults aged between 18 and 25 years who had been charged with serious criminal offences and referred to either a specialised institutional measure for young adults (SPC Art. 61) or outpatient treatment (SPC Art. 63). Our research questions were: (1) Can different raters score the YAPD dimensions (sum scores) with adequate interrater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] >0.75)? (2) Can YAPD dimensions predict individuals diagnosed with severe personality development disorder? (3) Can YAPD dimensions predict individuals who require specialised institutional treatment?

A summary study protocol was prepared in German prior to data collection and is available upon request from the corresponding author. To enable transparency and consistency in the reporting of methods and results, the STARD reporting guidelines [18] were followed. The competence check by the Ethics Committee of the Canton of Zurich revealed that this file-based research project did not fall within the scope of the Human Research Act and therefore did not require approval by the Ethics Committee (Req-2023-00548 dated 3 May 2023).

Data collection included files of all cases who underwent a final or precautionary measure under SPC Article 61 or a measure under SPC Article 63 (control group) ordered by the probation and correctional services of the Canton of Zurich from 1 January 2007 to 31 December 2020, and who were aged 18 to 25 at the time of entry into the measure (retrospective study design, consecutive series of the years from 2007 to 2020). The control group consisted of individuals given outpatient treatment, a less serious measure. The following exclusion criteria were defined for the present study: (1) a previous measure under SPC Article 61 (in another canton or before a measure under SPC Article 63); (2) the absence of a court decision (with the order of measures) or an expert opinion (with the indication for measures); (3) non-availability of the files (e.g. files by a court or another authority); and (4) no measure according to SPC Article 61 or 63 listed in the corresponding files. Relevant subjects were identified on 1 October 2021 by means of an analysis of the legal information system (Rechtsinformationssystem) of the Canton of Zurich, resulting in 257 relevant cases. Of these cases, 23 were excluded (4 because of a previous measure under SPC Article 61; 5 because of a missing court decision/expert opinion; 13 because of missing files; and 1 because of no measure listed in the files, possibly due to an error in the legal information system). The final sample consisted of 234 cases, comprised of 234 young adult males (mean age at the time of the expert opinion: 21.33 years, SD: 1.74 years), 126 of whom were subjects with a measure under Article 61 and 108 subjects with a measure under Article 63 (figure 1). No young adult females with measures under SPC Article 63 or 61 were reported in the period 2007–2020.

Figure 1Flowchart. SPC: Swiss Penal Code; YA: young adult; YAPD: young adult personality development.

A systematic analysis of the files from the probation and correctional services of Zurich was conducted. Data collection was carried out in a web-based system (REDCap [19]) using an integrated codebook, which included the definition and anchor examples of the variables. Based on 10 randomly selected cases, the codebook was tested and continuously adapted. After training on an additional 10 cases, an interrater survey involving a further 20 randomly selected cases was conducted among three raters with sufficient levels of criminal psychology knowledge. Explanations for demographic, criminality and psychiatric disorder variables are shown in the appendix, section 2.

The YAPD instrument encompasses 15 questions based on three dimensions (YAPD environmental, YAPD pathology, YAPD developmental tasks failure). Raters are prompted to consider information on developmental factors from all sources (police and juridical files, explorations, reports, etc.). YAPD items were guided by one to three questions and illustrated by examples. Before rating, each item was justified by listing relevant arguments to what extent a person deviates from normative development (referring to a prototype of the same age). Subsequently, the items were rated as strong indication (2), slight indication (1) or no indication (0) for the presence of a developmental tasks failure. There was no possibility of declaring unclear or missing information (items should be scored in the direction of lower risk with no / unclear information). According to the principles of structured professional judgement, a decision as to the presence of a full or partly severe personality development disorder should be made by clinicians according to their individual weighting of items. However, in the current file-based study, no overall clinical rating was available due to limited information in the files and the limited forensic expertise of the raters; therefore we used item-sum scores on the dimensions to test the reliability and validity of the instrument.

The student’s t-test (for continuous measures) and the χ2-test/Fisher’s exact test (for categorical measures) were used to analyse demographics, criminality and psychiatric disorders within the two subsamples (SPC Art. 61 vs SPC Art. 63). Cohen’s d (interpretation: >0.20 small effect, >0.50 medium effect, >0.80 large effect) and Cohen’sw (interpretation: >0.10 small effect, >0.3 medium effect, >0.50 large effect) were calculated as effect sizes for t-tests and the χ2-test/Fisher’s exact tests, respectively [20]. A two-way random-effects model and an absolute intraclass correlation coefficient agreement [21] were used for analysing the interrater reliability of the YAPD via three independent raters (a senior researcher and forensic expert [MA], and two master’s students in psychology/criminology [KN, MK]). Koo and Li [21] provided the following suggestion for interpreting intraclass correlation coefficients: below 0.50: poor; between 0.50 and 0.75: moderate; between 0.75 and 0.90: good; above 0.90: excellent. Cronbach’s α was used to analyse the internal consistencies of the YAPD dimensions with more than two items. Internal consistency was considered adequate if α >0.7 (22).

Multiple logistic regressions were used to analyse the three YAPD dimensions as predictors of sample status and the presence of severe personality development disorder. Additional post-hoc analyses with age, foreign nationality, low SES and any psychiatric disorder as covariates were performed because these variables were found to differ between subsamples (see below) or were previously found to be related to a developmental disorder and criminal behaviours [1, 10, 22]. Cases with missing values for covariates or outcomes were excluded from regression analyses. All analyses were performed in R statistics software, version 4.2.3 [23], with the tidyverse [24] and gmodels [25] packages. The data and code cannot be published openly due to internal restrictions of the Office of Corrections and Rehabilitation. However, the data and code are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Young male adults were aged between 18.46 and 24.97 years (mean: 21.89 years, SD: 1.62 years) at the time of measurement; 93 (39.7%) were of foreign nationality, 226 (97.0%) were single (vs married/divorced) and 92 (42.2%) were of low socioeconomic status (SES). Descriptive findings of the total sample and the subsamples are shown in table 1. Individuals given specialised institutional treatment (SPC Art. 61) were younger and more frequently of foreign nationality than individuals given outpatient treatment (SPC Art. 63), although effect sizes were small to medium. Prior adjudications/convictions were usual (200, 85.6%), and a large proportion committed property (65.5%) or violent (48.7%) crimes. No significant differences between the two samples were found regarding previous or current offences. Psychiatric disorders were highly prevalent (214, 91.5%), with most individuals suffering from substance use (140, 59.8%) or personality disorders (99, 42.3%). Individuals given specialised institutional treatment less frequently showed schizophrenic disorders than individuals prescribed outpatient treatment (table 1). In 12 forensic expert reports, no information on the presence of severe personality development disorder was available (e.g. experts did not consider personality development disorder as relevant). Almost all individuals in the specialised institutional treatment sample (113, 92.6%), but also a high number of individuals in the outpatient treatment sample (62, 62.0%), showed severe personality development disorder. Sum scores on the YAPD dimensions between the two samples are shown in table 2. YAPD environmental and YAPD developmental tasks failure were found to be higher, and YAPD pathology was found to be lower in specialised institutional treatment compared to outpatient treatment.

Table 1Sociodemographic information, offences and psychiatric disorders in total sample and subsamples.

| Variables | Missing values, n and % | Total sample (n = 234) | Subsample 1: Young adult specialised institutional treatment, SPC Art. 61 (n = 126) | Subsample 2: Outpatient treatment, SPC Art. 63 (n = 108) | Test statistic *(df) | p-value (effect size) | ||||||

| Sociodemographic information | ||||||||||||

| …Age in years at start of measure, mean and SD | 0 | (0.0%) | 21.89 | (1.62) | 21.51 | (1.57) | 22.33 | (1.58) | −3.95 | (232) | <0.001 | (0.518)** |

| …Foreign nationality, n and % | 0 | (0.0%) | 93 | (39.7%) | 60 | (47.6%) | 33 | (30.6%) | 6.38 | (1) | 0.012 | (0.174)*** |

| …Single (vs married/divorced), n and % | 1 | (0.4%) | 226 | (97.0%) | 123 | (97.6%) | 103 | (96.3%) | – | 0.706 | (0.039)*** | |

| …Low socioeconomic status, n and % | 21 | (9.0%) | 92 | (43.2%) | 55 | (47.4%) | 37 | (38.1%) | 1.49 | (1) | 0.222 | (0.093)*** |

| Prior and current offences, n and % | ||||||||||||

| …Prior adjudication/conviction | 0 | (0.0%) | 200 | (85.6%) | 115 | (91.3%) | 85 | (78.7%) | 6.42 | (1) | 0.011 | (0.178)*** |

| …Prior adjudications/conviction for violent offence | 0 | (0.0%) | 135 | (57.7%) | 76 | (60.3%) | 59 | (54.6%) | 0.56 | (1) | 0.456 | (0.057)*** |

| …Current violent offence | 2 | (0.8%) | 113 | (48.7%) | 66 | (53.2%) | 47 | (43.5%) | 1.81 | (1) | 0.179 | (0.097)*** |

| …Current sexual offence | 2 | (0.8%) | 23 | (9.9%) | 9 | (7.3%) | 14 | (13.0%) | 1.51 | (1) | 0.219 | (0.095)*** |

| …Current property offence | 2 | (0.8%) | 152 | (65.5%) | 91 | (73.4%) | 61 | (56.5%) | 6.57 | (1) | 0.010 | (0.177)*** |

| Psychiatric disorders, n and % | ||||||||||||

| …Substance use disorder | 0 | (0.0%) | 140 | (59.8%) | 73 | (57.9%) | 67 | (62.0%) | 0.25 | (1) | 0.614 | (0.042)*** |

| …Schizophrenic disorder | 0 | (0.0%) | 17 | (7.3%) | 2 | (1.6%) | 15 | (13.9%) | – | <0.001 | (0.236)*** | |

| …Emotional disorder | 0 | (0.0%) | 26 | (11.1%) | 14 | (11.1%) | 12 | (11.1%) | 0.00 | (1) | 1.00 | (0.000)*** |

| …Any personality disorder | 0 | (0.0%) | 99 | (42.3%) | 56 | (44.4%) | 43 | (39.8%) | 0.34 | (1) | 0.561 | (0.047)*** |

| …Antisocial personality disorder | 0 | (0.0%) | 59 | (25.2%) | 38 | (30.2%) | 21 | (19.4%) | 3.00 | (1) | 0.084 | (0.123)*** |

| …Other psychiatric disorder | 0 | (0.0%) | 82 | (35.0%) | 47 | (37.3%) | 35 | (32.4%) | 0.42 | (1) | 0.519 | (0.051)*** |

| …Any psychiatric disorder | 0 | (0.0%) | 214 | (91.5%) | 113 | (89.7%) | 101 | (93.5%) | 0.66 | (1) | 0.417 | (0.068)*** |

| …Severe personality development disorder | 12 | (5.1%) | 175 | (78.8%) | 113 | (92.6%) | 62 | (62.0%) | 29.07 | (1) | <0.001 | (0.373)*** |

df: degrees of freedom; SPC: Swiss Penal Code.

* t-test, χ2-testor Fisher’s exact test.

** Cohen’s d (>0.20: small effect; >0.50: medium effect; >0.80: large effect).

*** Cohen’s w (>0.10: small effect; >0.3: medium effect; >0.50: large effect).

Table 2Internal consistencies and means of the YAPD dimensions.

| Variables | Internal consistency, Cronbach’s a and 95% CI | Total sample (n = 234) | Subsample 1: Young adult specialised institutional treatment, SPC Art. 61 (n = 126) | Subsample 2: Outpatient treatment, SPC Art. 63 (n = 108) | Test statistic * (df) | p-value (Cohen’s d) | ||||||

| YAPD environmental, mean and SD | 0.67 | (0.58–0.73) | 3.18 | (1.84) | 3.52 | (1.63) | 2.79 | (2.00) | 3.02 | (206.15) | 0.002 | (0.40)** |

| YAPD pathology, mean and SD | – | 2.01 | (0.78) | 1.90 | (0.66) | 2.14 | (0.88) | −2.32 | (232) | 0.021 | (0.31)** | |

| YAPD developmental tasks failure, mean and SD | 0.75 | (0.70–0.79) | 11.33 | (4.79) | 12.65 | (3.98) | 9.79 | (5.20) | 4.67 | (198.41) | <0.001 | (0.62)** |

CI: confidence interval; df: degrees of freedom; SPC: Swiss Penal Code; YAPD: Young Adult Personality Development.

* t-test

** Cohen’s d (>0.20: small effect; >0.50: medium effect; >0.80: large effect).

Internal consistencies determined by Cronbach’s α values are shown in table 2 for YAPD dimensions with more than two items. The following ICC were found for the three dimensions of the YAPD based on 20 cases with three raters: YAPD environmental: ICC = 0.92 (95% CI = 0.82–0.96), F = 12.8, (degrees of freedom 1 [df1] = 19, df2 = 36.6), p <0.001; YAPD pathology: ICC = 0.74 (95% CI = 0.45–0.89), F = 4.39, (df1 = 19, df2 = 29.3), p <0.001; YAPD developmental task failure: ICC = 0.91 (95% CI = 0.68–0.97), F = 18.4, (df1 = 19, df2 = 8.68), p <0.001.

The findings from multiple and logistic regressions with the YAPD dimensions as predictors, with Age, Foreign nationality, Low SES or Any psychiatric disorder as covariates and Sample status and Severe personality development disorder as outcomes are shown in table 3. In all analyses performed, YAPD development tasks failure positively predicted specialised institutional treatment (compared to outpatient treatment) and the presence of severe personality development disorder. YAPD pathology negatively predicted young adult specialised institutional treatment but was not found to be related to the presence of severe personality development disorder. Finally, YAPD environmental positively predicted severe personality development disorder in multiple logistic regressions without covariates but not when these variables were included.

Table 3Findings of logistic regression analyses with the YAPD as a predictor of young adult specialised institutional treatment and severe personality development disorder.

| Outcome: Young adult specialised institutional treatment (vs outpatient treatment) | Outcome: Severe personality development disorder | ||||||||||||

| Model 1 (n = 234) | Model 2 (n = 213) | Model 3 (n = 222) | Model 4 (n = 201) | ||||||||||

| OR and 95% CI | p-value | OR and 95% CI | p-value | OR and 95% CI | p-value | OR and 95% CI | p-value | ||||||

| Predictors | YAPD environmental (0–6) | 1.18 | (1.00–1.41) | 0.055 | 1.15 | (0.95–1.40) | 0.148 | 1.42 | (1.15–1.80) | 0.002 | 1.26 | (0.99–1.62) | 0.064 |

| YAPD pathology (0–4) | 0.47 | (0.31–0.69) | <0.001 | 0.39 | (0.22–0.65) | <0.001 | 0.86 | (0.55–1.36) | 0.517 | 0.82 | (0.44–1.60) | 0.539 | |

| YAPD developmental tasks failure (0–22) | 1.16 | (1.08–1.24) | <0.001 | 1.19 | (1.10–1.30) | <0.001 | 1.21 | (1.11–1.32) | <0.001 | 1.20 | (1.09–1.33) | <0.001 | |

| Covariates | Age (18.46–24.97 years) | – | 0.79 | (0.65–0.97) | 0.024 | – | 0.67 | (0.51–0.87) | 0.004 | ||||

| Foreign nationality (yes = 1 vs no = 0) | – | 2.36 | (1.18–4.82) | 0.016 | – | 1.79 | (0.71–4.80) | 0.228 | |||||

| Low socioeconomic status (yes = 1 vs no = 0) | – | 0.81 | (0.40–1.62) | 0.560 | – | 2.18 | (0.87–5.85) | 0.105 | |||||

| Any psychiatric disorder (yes = 1 vs no = 0) | – | 1.29 | (0.31–5.32) | 0.719 | – | 1.43 | (0.28–6.79) | 0.657 | |||||

| Model parameter | Model χ2, p-value | 38.64 | <0.001 | 54.14 | <0.001 | 49.96 | <0.001 | 54.15 | <0.001 | ||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.37 | |||||||||

CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; YAPD: Young Adult Personality Development.

Addressing the lack of validated instruments for assessing psychosocial maturity, the present study tested the Young Adult Personality Development (YAPD) as an instrument for diagnosing severe personality development disorder in young adults. Such diagnoses are important for juridical decision-making worldwide and specifically in Switzerland for identifying young adults needing specialised institutional measures. Judges have had to rely on reliable psychiatric-psychological expertise [26]. Because severe personality development disorder is not described in the current classification schemas for psychiatric disorders (ICD, DSM), forensic experts have had to rely on unclear criteria and diagnoses and are vulnerable to bias [3, 15]. The YAPD was introduced in 2021 [15] and is based on an extensive literature review in German-speaking countries [e.g. 27, 28]. The YAPD considers all facets (“temperance”, “perspective” and “responsibility”) that were reported by previous research on psychosocial maturity [8–13]. The YAPD might have served as an adequate instrument to guide forensic decision-making; however a validation study was missing until now. The finding that no women could be included in this study is remarkable, given that approximately 5% of serious crimes in young adulthood are committed by females (14). The lack of appropriate institutions for young adult female measures may have contributed to this finding.

The present study found personality development disorder highly prevalent (78.8%) in a sample of young male adults who were adjudicated or convicted of serious offences. According to expert opinions, not only individuals in specialised institutional settings (92.6%) but also a high number of young adults in outpatient treatment settings (62%) show severe developmental disorders. Because the presence of severe personality development disorder is the only inclusion criterion for a Swiss Penal Code (SPC) measure (Article 61) but not for SPC Article 63, this finding was rather unexpected. Obviously, other criteria (e.g. comorbid psychiatric disorders, current living situation and employment/education) were also found to be relevant for deciding on which measure is more accurate. Interestingly, in 12 cases, no information was available on severe developmental disorder. This finding may reflect the heterogeneity in the quality of written reports in Switzerland [26].

The current study found moderate-to-adequate internal consistencies [29] and an excellent interrater reliability (ICC: >0.90) for the YAPD environmental and YAPD developmental tasks failure dimensions. The interrater reliability value for YAPD pathology was close to acceptable (ICC: 0.74). For training purposes, but also for final decision-making, we recommend that two experienced forensic practitioners use the YAPD independently after sufficient information has been collected on the young adult in focus.

Two variables were chosen as diagnostic validation criteria, namely psychiatric expert opinion on the presence of severe personality development disorder and a juridical decision on a young adult-specialised institutional measure (compared to outpatient treatment only). Both variables, however, may not reflect a general “gold standard” of assessing disorders. Structured interviews based on internationally defined diagnostic criteria are ideal for diagnostic decision-making [30], but such instruments are currently unavailable for assessing developmental disorders [15]. However, both validation measures reflect the clinical and juridical practice of actual decision-making. Our findings support the YAPD developmental tasks failure and to a lesser degree the YAPD environmental dimensions as valid dimensions for diagnosing severe personality development disorder with subsequent institutional measures. Interestingly, contrary to previous findings [27], the YAPD pathology dimension was found to be unrelated to the presence of a severe personality development disorder and negatively related to a specialised institutional measure. The YAPD pathology dimension did not appear to assess the impact of early psychiatric and somatic disorders on later personality development but more the impact of current psychiatric morbidity as an entry criterion of the control group with outpatient treatment. A revised version of the instrument should further specify the items in the pathology dimension. Because this scale consists of only two items, clinicians should focus on the other dimensions of the YAPD to assess severe personality developmental disorder.

Based on a representative sample with a consecutive series of file cases from 2007 to 2020, this study addressed an important subject for young adults who have committed criminal offences [9]. The following limitations should be noted: (1) This study was based on files of the Canton of Zurich, and the findings probably do not directly generalise to other cantons/countries. (2) No females could be included in this study. The gender specificity of the sample may limit the generalisability of the findings to males. (3) Sum scores on the items of the three YAPD dimensions were validated, whereas no overall decisions based on the principles of SPJ were available. (4) Two meaningful outcome measures were defined as validation criteria that reflect current psychiatric and juridical decisions. However, these criteria may not reflect a diagnostic gold standard in a narrow sense.

Based on this study’s findings, the YAPD environmental and YAPD developmental tasks failure dimensions can be recommended for use in clinical practice. Psychological and psychiatric experts should use these YAPD dimensions in the forensic assessment of young adults to reduce bias in decision-making. The concept of psychosocial maturity and the YAPD might be further considered by forensic therapists to manage personality development-related risks and progress. A further revision of the YAPD pathology dimension seems necessary, and additional validation studies should also test the YAPD as a predictor of criminal recidivism in young adults.

Individual deidentified participant data (including the codebook in German) will be shared by request to the corresponding author (see below) for researchers who provide a sound methodological rationale. Data will be available immediately after publication of the article with no end date and delivered to achieve the aims in the proposal. No other documents are available.

The authors are grateful to Yannick Lüthi and collaborators at the Offices of Correction and Rehabilitation who helped with file acquisition. We also thank Linda Skjelsvik and Maria Krasnova for their support in data collection and processing. We thank Astrid Rossegger, Jérôme Endrass and the other collaborators of the research and development team for their helpful comments on this study’s concept.

This study received no funding.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. – Marcel Aebi received support for costs of article processing and English proofreading (relevant to this article) from Corrections and Rehabilitation, Department of Justice and Home Affairs, Canton of Zurich, Switzerland, the University of Konstanz, Germany, and University of Zurich, Switzerland. He received in the last five years royalties from Hogrefe for his authorship of books on juvenile aggression and delinquency. – Jana Dreyer received support for the costs of article editing and English proofreading (related to this article) and internal meetings (unrelevant for this article) from the Office for Corrections and Rehabilitation, Department of Justice and Police, Canton of Zurich, Switzerland. – Christoph Siedler received support for the costs of article editing and English proofreading from the Office for Corrections and Rehabilitation, Department of Justice and Police, Canton of Zurich, Switzerland. – Karoline Niedenzu: nothing to declare. – Évi Forgó Baer received support for costs of article processing (relevant to this article) and internal meetings (not relevant to this article) from Corrections and Rehabilitation, Department of Justice and Home Affairs, Canton of Zurich, Switzerland. Payment or honoraria for lectures from “Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften” (ZHAW), unrelated to this article. She received in the last five years royalties from Hogrefe for his authorship of books on juvenile aggression and delinquency. – Carmelo Campanello received support for costs of article processing and English proofreading (relevant to this article) from Corrections and Rehabilitation, Department of Justice and Home Affairs, Canton of Zurich, Switzerland. – Andreas Wepfer: nothing to declare. – Francesco Castelli received support for costs of article processing and English proofreading (relevant to this article) from Corrections and Rehabilitation, Department of Justice and Home Affairs, Canton of Zurich, Switzerland. – Thierry Urwyler received support for costs of article processing and English proofreading (relevant to this article) from Corrections and Rehabilitation, Department of Justice and Home Affairs, Canton of Zurich, Switzerland.

1. Bryan-Hancock C, Casey S. Psychological maturity of at-risk juveniles, young adults and adults: implications for the justice system. Psychiatr Psychol Law. 2010;17(1):57–69.

2. Nixon TS. The Relationships between Age, Psychosocial Maturity, and Criminal Behavior [dissertation]. Cincinnati (OH): University of Cincinnati; 2020.

3. Welner M, DeLisi M, Knous-Westfall HM, Salsberg D, Janusewski T. Forensic assessment of criminal maturity in juvenile homicide offenders in the United States. Forensic Sci Int Mind Law. 2023;4:100112.

4. Galambos NL, MacDonald SW, Naphtali C, Cohen AL, de Frias CM. Cognitive performance differentiates selected aspects of psychosocial maturity in adolescence. Dev Neuropsychol. 2005;28(1):473–92.

5. Havighurst RJ. Developmental tasks and education. 3rd ed. Boston: Addison-Wesley Longman Ltd; 1972.

6. Manning ML. Havighurst’s developmental tasks, young adolescents, and diversity. Clearing House. 2002;76(2):75–8.

7. Steinberg L, Cauffman E. Maturity of judgment in adolescence: psychosocial factors in adolescent decision making. Law Hum Behav. 1996;20(3):249–72.

8. Monahan KC, Steinberg L, Cauffman E, Mulvey EP. Trajectories of antisocial behavior and psychosocial maturity from adolescence to young adulthood. Dev Psychol. 2009 Nov;45(6):1654–68.

9. Monahan KC, Steinberg L, Cauffman E, Mulvey EP. Psychosocial (im)maturity from adolescence to early adulthood: distinguishing between adolescence-limited and persisting antisocial behavior. Dev Psychopathol. 2013 Nov;25(4 Pt 1 4pt1):1093–105.

10. Steinberg LD, Cauffman E, Monahan K. Psychosocial maturity and desistance from crime in a sample of serious juvenile offenders. Washington (DC): US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2015., Available from https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh176/files/pubs/248391.pdf

11. Cruise KR, Fernandez K, McCoy WK, Guy LS, Colwell LH, Douglas TR. The influence of psychosocial maturity on adolescent offenders’ delinquent behavior. Youth Violence Juv Justice. 2008;6(2):178–94.

12. Ozkan T, Worrall JL. A psychosocial test of the maturity gap thesis. Crim Just & Behav. 2017;44(6):815-42. https://doi.org/

13. Dünkel F, Geng B, Passow D. Erkenntnisse der Neurowissenschaften zur Gehirnreifung. Argumenten für ein Jungtäterstrafrecht [German.]. Zeitschrift für Jugendkriminalrecht und Jugendhilfe. 2017;28(2):123–9.

14. Aebi M, Fenner C, Schlüsselberger M, Urwyler T, Sidler C. Massnahmenanordnungen bei jungen Erwachsenen: Ergebnisse einer empirischen Untersuchung im Kanton Zürich [German.]. NKrim. 2023;1/2023:25–39.

15. Urwyler T, Sidler C, Aebi M. Massnahmen für junge Erwachsene nach Art. 61 StGB: Beurteilung der erheblich gestörten Persönlichkeitsentwicklung: Helbing Lichtenhahn Verlag; 2021.

16. Frischknecht T, Schneider E, Schmalbach S. Welcher Psy-Experte darf’s denn sein? Kritische Überlegungen zur Auswahl von psychiatrischen und psychologischen Sachverständigen im Strafverfahren. Jusletter [Internet]. 2012. Available from: https://jusletter.weblaw.ch/juslissues/2012/664/_10287.html__ONCE&login=false

17. Habermeyer E, Graf M, Noll T, Urbaniok F. Psychologen als Gutachter in Strafverfahren. Wie weiter nach dem Bundesgerichtsurteil BGer 6B_884/2014 vom 8. April 2015? [German.]. Aktuelle Juristische Praxis. 2016;2:127–34.

18. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig L, et al.; STARD Group. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ. 2015 Oct;351:h5527.

19. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, et al.; REDCap Consortium. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019 Jul;95:103208.

20. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc. New Jersey: Hillsdale; 1988.

21. Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016 Jun;15(2):155–63.

22. Bessler C, Stiefel D, Barra S, Plattner B, Aebi M. Psychische Störungen und kriminelle Rückfälle bei männlichen jugendlichen Gefängnisinsassen [Mental disorders and criminal recidivism in male juvenile prisoners]. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2019 Jan;47(1):73–88.

23. R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2022.

24. Wickham H, Wickham MH. Package tidyverse 2. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/tidyverse/tidyverse.pdf

25. Warnes GR, Bolker B, Lumley T, Warnes MG, Imports M. Package ‘gmodels’ 2018. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gmodels/gmodels.pdf

26. Bevilacqua L, Caflisch A, Endrass J, Rossegger A, Hachtel H, Graf M. Expert opinions on criminal law cases in Switzerland–an empirical pilot study. SMW. 2023;153(5):40073. doi: https://doi.org/10.57187/smw.2023.40073

27. Esser G, Fritz A, Schmidt MH. Die Beurteilung der sittlichen Reife Heranwachsender im Sinne des § 105 JGG–Versuch einer Operationalisierung [German.]. Monatsschr Kriminol. 1991;74(6):356–68. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/mks-1991-740603

28. von Buch J, Köhler D. Jugendlich oder erwachsen? RPsych. 2019;5(2):178–205. doi: https://doi.org/10.5771/2365-1083-2019-2-178

29. Nunnally JC. Psychometric Theory. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill; 1978.

30. Shabani A, Masoumian S, Zamirinejad S, Hejri M, Pirmorad T, Yaghmaeezadeh H. Psychometric properties of structured clinical interview for DSM‐5 Disorders‐Clinician Version (SCID‐5‐CV). Brain Behav. 2021 May;11(5):e01894.

The appendix is available in the pdf version of the article at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.3793.