Implementing systematic outcome assessments in a Swiss healthcare practice: points to consider

Franziska Saxer, Markus Degen, Dominique Brodbeck

Introduction

The Swiss health authorities have increased their efforts to improve quality and efficiency in the healthcare system by requesting healthcare providers and their organisations to implement systematic quality management at the institutional and national level. Monitoring of outcomes related to treatment quality will be part of corresponding quality programmes, hence requiring a systematic outcome assessment. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) will probably be included in these assessments to capture patient relevant aspects. Many Swiss healthcare practices have started to develop local implementation plans for a systematic outcome assessment and they can build on existing guidelines and frameworks. However, peculiarities of the Swiss healthcare system impose additional challenges and opportunities. Some points to be considered in planning local implementation are discussed in this article.

Background

The quality of medical treatment is a multifaceted construct. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined quality of care as “the extent to which health care services provided to individuals and patient populations improve desired health outcomes. In order to achieve this, health care must be safe, effective, timely, efficient, equitable and people-centred.” These aspects, although ingrained into the daily work of providers, are difficult to measure. Mainly the Scandinavian countries therefore introduced systematic data collection in the form of registries, for example for follow-up after joint replacements [1, 2]. Initially, the outcome was assessed via the occurrence of repeat surgery or, for other treatments, change of treatment approach. This implies that treatment failure for whatever reason was implicated as absence of quality. This attitude is partly changing. With the further development and recognition of patient-centred outcome assessments, patient reported outcome and experience scores (PROMs/PREMs) have increasingly been implemented for systematic outcome assessments. These not only capture patient-relevant aspects but also allow an evaluation of treatment efficiency in the health economic context.

In 2009, the National Health Service (NHS) in England started pioneering work by introducing a mandatory use of PROMs and PREMs for a structured follow-up of patients after hip or knee replacement, hernia repair or varicose vein surgery [3]. This initiative – involving hundreds of providers and more than 70,000 patients per year – demonstrated that large-scale systematic outcome assessments are feasible and allowed to address some potential methodological challenges [4, 5]. All over the world individual health care providers and hospital departments have started local initiatives to collect PROMs and PREMs. It has been increasingly recognised that such a systematic outcome assessment is an important tool to improve quality of health care both at the level of the individual patient and at the system level [6–9].

In June 2019, the Swiss parliament revised the federal legislation on health insurance to enforce quality assessments in the context of healthcare provision. A national quality commission will coordinate and initiate activities on quality improvement in health care. Quality contracts between healthcare provider associations and health insurance associations will define obligatory quality measures, which have to be adopted by all healthcare providers in order to participate in public reimbursement schemes. It is to be expected that systematic outcome assessments will be part of these contracts, and in consequence many practices have started to think about implementing such assessments. This will imply a substantial change from the current, rather sporadic attempts of a systematic outcome assessments, like the obligatory review plans of the Swiss National Association for Quality Development in Hospitals and Clinics (ANQ) or the voluntary registries of the Working Group for Quality Assurance in Surgery (AQC).

In the current period of change, practices can follow existing international guidelines and frameworks for the implementation of systematic assessments, summarising the international experience from many projects [10–13]. However, there are some peculiarities of the Swiss healthcare system that have a direct impact on the implementation of systematic measures. Below, we discuss five aspects, which in our opinion require additional attention when a practice starts to design plans for a local implementation of systematic outcome assessments. The consequences for a practice are summarised at the end of each point.

By “healthcare practice” we mean an organisational unit that is the natural starting point for the organisation of systematic outcome assessments. This “unit” can be a specific department at any hospital, a specialised clinic, a group practice or a practice group or the practice of one individual healthcare provider. In contrast, we use the term “healthcare provider” mainly for the individual providers, typically working together in such a unit.

Point 1: The multiple aims of a systematic outcome assessment

Systematic quality monitoring based on quality indicators is a cornerstone of any quality management [14, 15]. Many of such indicators are already measured at the level of a single patient, such as waiting time or the occurrence of complications. The distribution of such a variable across the patients of one given practice can then be compared with a national or international standard. Current plans for systematic outcome assessments add new indicators, such as a quality-of-life score. This adds new dimensions compared with existing indicators by focusing on long-term patient-relevant outcomes and on patient experience. When considering the aims of such an extension, it is useful to distinguish between internal and external quality monitoring.

Internal quality monitoring is aimed at ensuring a uniform treatment quality for the patients of a practice at a level corresponding to national or international standards. Technically, this implies a systematic search for deviations from uniformity, for example over time, across different patient populations or at the level of a single patient. In many practices such a systematic monitoring is not yet well established owing to insufficient structured documentation of relevant quality indicators. Consequently, one aim when implementing systematic outcome assessments can be to boost internal quality monitoring by extending the documentation basis substantially. This requires a vision of how to use the additional data to perform internal monitoring in future. Feedback to providers is a central aspect in this context. Accordingly, the definition of the content of regular reports forms the cornerstone of such a plan. Allowing comparisons across individual providers within a practice or sharing results on a voluntary basis within a practice network can be crucial decisions to be addressed in such a plan.

External quality monitoring is characterised by the obligatory sharing of information on quality indicators with healthcare authorities or other bodies. In this context, aims and reporting techniques are defined by the authorities. How data from systematic outcome assessments will be used in Switzerland for external monitoring is currently the topic of negotiations between provider, healthcare regulator and insurance associations. It is to be expected though that the techniques already established in connection with the activities of the ANQ will continue to be used. These range from confronting hospitals with their outcome for single indicators relative to all other hospitals and then making these comparisons publically available. In the long run, outcome assessments may be also used directly to trigger reimbursement as part of moving towards a value-based healthcare system [16–18].

However, it is important to be aware that data from systematic outcome assessments can also be used outside of the context of quality monitoring. For example, these data can support activities in internal quality management. Single case evaluations in the form of case discussions, morbidity and mortality meetings, critical incident reporting systems, etc. can benefit from additional information based on PROMs and PREMs from systematic assessments, thereby giving a more complete picture of the individual case. PROMs and PREMs may also help to identify individual cases of interest.

Data from PROMs and PREMs have been also used successfully to improve dialogue with patients and to support patient care. Already in 2001, a randomised controlled clinical trial demonstrated that monitoring of well-being via PROMS and subsequent discussion with patients can improve clinical outcomes and the patient’s perception of care [19]. Since then many different ways of using PROMs and PREMS to improve individual care have been considered and their value is evaluated in various reviews [20–22]. The simplest approach is to collect outcome data prior to a (follow-up) visit and to use these patient-specific data to prepare the conversation with the patient at a personal consultation. Patient and provider can benefit from the fact that patients might be more able or willing to describe their situation when filling out a questionnaire than in a direct conversation. It might also help them to focus on some key aspects. More sophisticated applications may also allow the generation of automatic alerts if the results of PROMs or PREMs show a negative tendency, which in turn could help providers to actively follow up these patients. PROMs-based baseline assessments may also help to define individual goals such as sporting activity vs playing a musical instrument.

To support patients in their choice of a provider, outcome assessments can be also used for marketing purposes. For example, a practice may inform potential clients about the outcomes and degree of satisfaction they can expect. To an increasing degree, systematic outcome assessments will play an integral part in certification processes. In addition, systematic outcome assessments can make a practice more attractive as a partner for research, for example by participating in registries or multicentre projects. It may even foster initiation of research activities within the practice.

- Systematic outcome assessment should not solely be perceived as yet another task responding to the requirements of Swiss health authorities. The current motion provides many further opportunities, which may be of direct benefit to the participating practice.

- The practice should have a clear picture of the intended internal use of the collected data and resultant analyses. For each aim, a clear plan of action should be defined, in particular with respect to the use in internal monitoring.

Point 2: The role of the healthcare practice in patient management

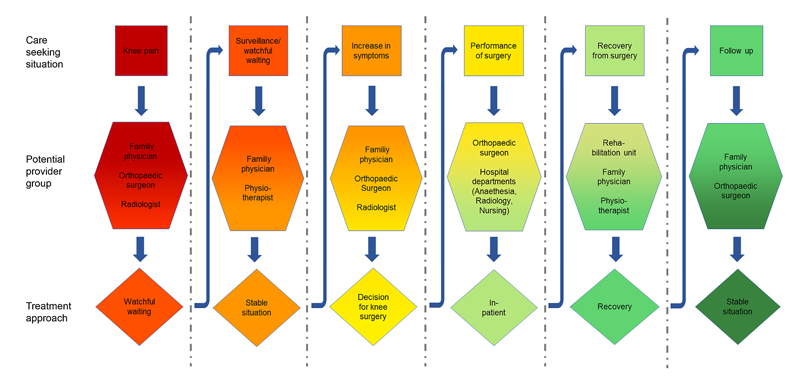

The Swiss healthcare system is highly fragmented. Typically, many different health service providers are involved in patient management over time, with partially overlapping responsibilities. Figure 1 illustrates this point by depicting a potential management path of a single patient from first presenting with knee pain to their family physician until long-term follow-up after treatment. In addition, the management pathways can substantially differ from patient to patient even in the case of similar needs, as standardised pathways in Switzerland are only available for certain pathologies, also due to cantonal or regional customs. The differences begin, for example, with the selection of the entry point. Some insurance models incentivise patient management via family physicians who refer patients to specialists if needed. This form of care flow is more typical in rural areas. In urban areas patients tend to seek out specialists directly or present at emergency departments without primarily consulting a family physician. The possibility of digital first consultations as offered by various providers but also insurers adds a further entry point. The entry point to a certain extent often already defines the subsequent care pathway.

Figure 1: Example of the management path for a patient experiencing knee pain.

The high fragmentation and the scarcity of standardised pathways imply a challenge for the evaluation of treatment quality. From a patient and a societal perspective the evaluation of the whole management chain is desirable. For an individual practice an evaluation of their specific contribution to the treatment chain is the natural objective. Both aspects are valid targets of systematic evaluations since a chain is as good as all its links and a single practice is the natural target for quality improvement activities. However, there is a certain danger of overlooking poor quality of the transitions between the links of the treatment chain.

A reasonable compromise is the definition of typical care-seeking situations in the management process in patients with similar medical conditions. Examples of care-seeking situations are the need for a primary diagnosis, the need for a differential diagnosis, the need for a treatment recommendation, the need of treatment delivery, etc. (see fig. 1). In this scenario the active parties per care-seeking situation are limited, which facilitates the definition of the individual contributions concerning the overall treatment quality in this specific care-seeking situation. Alternatively one provider or practice could take the lead and main responsibility for a specific care-seeking situation. The division of the whole care pathway into separately evaluated care-seeking phases allows the evaluation of the whole chain by evaluating its individual links. Finally the fragmentation of healthcare provision has some practical consequences for data collection. Patients may be more accessible for other providers during follow-up than for the initially treating practice. This aspect will be taken up again later.

● The practice must be aware of its role in patient management.

● The practice has to decide if the data collected in the practice should be interpreted as indication of

- its individual quality,

- the quality of a group of providers under the lead of the practice,

- the cumulative quality of many providers acting independently of the practice.

● There may be the need for a network of practices sharing responsibility in addressing a specific care seeking situation and a patient group, in order to allow a meaningful evaluation of treatment quality.

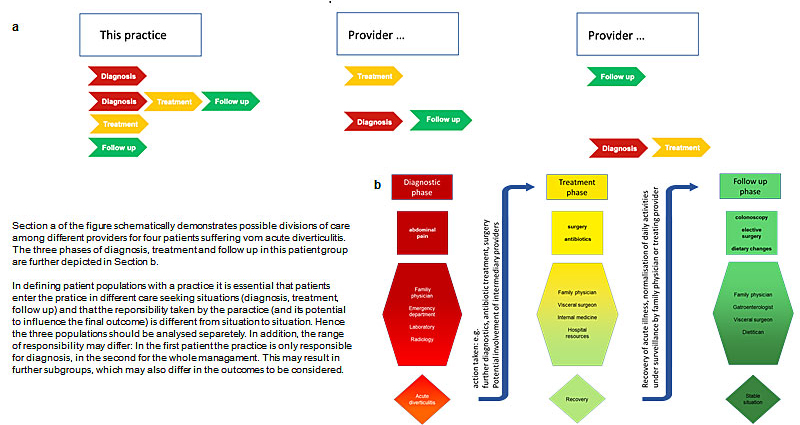

● In defining patient populations within the practice, the care seeking situation has to be taken into account and all patients should be followed. Figure 2 gives an example.

Figure 2: Division of care between different providers and the impact on the patient population of a practice. Section a of the figure schematically demonstrates possible divisions of care among different providers for four patients suffering vom acute diverticulitis. The three phases of diagnosis, treatment and follow up in this patient group are further depicted in Section b. In defining patient populations with a practice it is essential that patients enter the pratice in different care seeking situations (diagnosis, treatment, follow up) and that the reponsibility taken by the paractice (and its potential to influence the final outcome) is different from situation to situation. Hence the three populations should be analysed separetely. In addition, the range of responsibility may differ: In the first patient the practice is only responsible for diagnosis, in the second for the whole managament. This may result in further subgroups, which may also differ in the outcomes to be considered.

Point 3: The need for additional data

Assessing PROMs and PREMs at baseline and follow-up time points is an important step in evaluating patient-relevant aspects of treatment and outcome quality. However, the interpretation of these measures necessitates knowledge about patient characteristics, treatment characteristics (preferably over the complete patient care pathway) and other outcomes such as compliance with treatment, complications, laboratory or radiological findings, functional tests, mortality, etc. These are specifically important in understanding deviations from expected results and allowing the definition of corrective actions if necessary. Patient characteristics such age, disease stage and comorbidities are also essential for risk adjustments, allowing a fair comparison across practices is spite of differences in the patient populations.

Traditionally, in many healthcare settings data are archived in text form, for example the anamnesis or results of clinical examinations. This unstructured form of data collection is useful and sufficient for communication with individual patients or other providers involved in the management of single patients. However, many of the aims mentioned under point 1 require analysis of data systematically across patients. This makes it necessary to have access to the information in structured form, as numbers or predefined categories. In principle, the collection of structured data for quality management might be implemented as a separate activity, while keeping current documentation practice for daily routine. For example, a data manager may extract the information in structured form from the written records. Apart from the disadvantage of necessitating significant personal resources, this approach will probably often result in poor data quality, as the current way of reporting is little standardised and correct interpretation of a written record often requires involvement of the person who generated the record. Moreover, some data may not yet be recorded in any way.

There are already systems for the structured acquisition of medical information during the treatment process, such as Snomed CT, although the support of these systems in current practice information systems is not yet widespread. Often the "tagging" with structured medical terms is done in a second step after the data entry. Switzerland is a member of Snomed CT since 2016 and the use of this medical terminology is encouraged. Another approach combining human readable documents with structured sections is the HL7CDA Clinical Document Architecture, which is also used in the implementation of the document interoperability in the Electronic Health Record (EHR) in Switzerland.

Hence it could be wise to revise the whole clinical data management of a practice at the time of introducing a systematic outcome assessment, moving towards recording more data in a structured form from the beginning. Such a change in recording practice will require a relevant effort, especially since text-form data will still be preferable for communication with patients and other providers. A change of documentation practice though might prove more sustainable. Systems that allow the creation of text-form reports from structured data sets offer the opportunity to avoid the burden of a double workload. Also, further gains in efficiency are possible. For example data collected for official registries such as the Swiss National Joint Registry (SIRIS) or the Surgical Site Infections Surveillance administered by swissnoso are today typically recorded in separate data forms creating an additional administrative burden. This can be avoided by directly exporting the data from the clinical data system. Finally, availability of structured data makes it easier to participate in research-driven registries or other research activities. As a consequence of the high fragmentation of the Swiss healthcare system, additional data necessary for the correct interpretation of the outcome might be available, but stored with another provider – similar to the situation for the outcome assessment described above. This might be another reason to seek the collaboration within provider networks. In the long run it might also be of interest to incorporate data from other sources, such as the residents’ registration office or insurers.

- The practice has to ensure that relevant additional data are available in structured form and can be combined with the data from systematic outcome assessments.

- This often requires a very distinct change in the current documentation practice towards gathering more data in structured form. Implementing such a change may be much more challenging than organising the collection of PROMs, as the latter is a simple “add on” to the existing practice.

Point 4: The essential role of information technology

Data collection tools will form an integral and pivotal part of any efforts to implement systematic assessments in health care. Failure to find effective IT solutions can seriously endanger the implementation and, even more, the sustainability of quality programmes. PROMs and PREMs can today be collected using a variety of different techniques (such as paper, electronically readable forms, tablets, web-pages, smartphone applications, traditional telephone interviews, etc.). These can be used in different organisational settings during contact with healthcare providers or with impersonal contacts triggering filling out surveys at home. Especially follow-up assessments often suffer from a low response. Trying to match the survey technique to individual patient preferences is one important way of increasing the return rate. Nevertheless, a final attempt to contact non-responders by phone should be part of the overall contact strategy. To offer this flexibility and integrate the various response formats, potent IT solutions are vital. In any case, it is important to carefully design the data model for the PROMs in order to be able to evaluate the patient-entered data in different dimensions. The management of the survey can be at least partly automated with workflow engines that provide tools such as automatic triggering, quality tests, automatic reminders, etc.

The seamless integration of data collection into clinical routine, trying to minimise the burden for patients, providers and staff alike, has been identified as an essential requirement for successful implementation and sustainable performance of systematic outcome assessments [23, 24]. The need for changes in documentation practices outlined under point 3 enforces this requirement. Integration into clinical routine means here mainly integration into the existing user interface of the IT system of the practice. Improving dialogue with patients or the discussion of single cases as part of internal quality improvement requires adequate tools for (visual) presentation of the data of a single patient, preferable also within the local IT system. Ideas about data exchange with external partners or registries also require IT support.

The implementation of all these necessary measures will often not be feasible within the local IT resources at a single practice. It is hence a straightforward idea to seek collaboration with partners offering solutions suitable for many practices. There is an emerging market for such IT providers, ranging from start-ups such Heartbeat to traditional registry providers such as Adjumed to established technology companies such as Philips or globally active scientific organisations such as the AO . They all offer integration into or communication with existing local systems. However, healthcare practices in Switzerland use a multitude of IT solutions with limited used of established standards for data exchange. Many IT solutions have grown from imperfect options with continuous individual extensions, and some practices still rely mainly on paper documentation. Hence substantial efforts have to be expected in the local implementation.

- The practice needs a well-defined plan to extend its IT infrastructure in order to integrate the necessary data collection into the clinical routine.

- Practices may be overstrained with extending their local IT system in an adequate manner. Hence it is essential to find external partners to develop a local IT solution.

Point 5: The legal frame

Research with human subjects in Switzerland has been regulated since 2011 by the Human Research Act (HRA) and corresponding ordinances based on international principles such as good clinical practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. In specific situations other laws might be applicable, but the requirements in the context of patient consent and data handling especially are elaborated in the HRA. This includes data handling for research-oriented registries, which necessitates the absent of dissent by the patient but not an active consent or assent. In this regard the HRA overrules data protection laws. So does the cancer registry act, which regulated the procedures concerning the only legally required medical registry in Switzerland.

When collecting data to support quality assessments other legislative principles come into play, namely the data protection law and the legislative principles on medical confidentiality. These laws significantly restrict the collection and exchange of personal data without consent. Requiring explicit consent for a systematic outcome assessment introduces bias, as there is a high likelihood for an association between giving consent and the actual or expected outcome. Anonymisation of data sets limits the informative value and is organisationally demanding. The impact of the European Union General Data Protection Regulation on Switzerland currently remains also unclear, which does not simplify the situation.

The only guidance on this topic is a position paper by Swissethics [25] prompted by an apparent uncertainty within the scientific community about which projects to submit for approval by a competent ethics committee (i.e., only research projects). The difficulty lies in the continuum of characteristics that separate pure research from pure quality assessment. Swissethics, for example, defines the generation of new knowledge as characteristic for research, whereas the application of existing knowledge is supposed to characterise quality management. In the context of systematic outcome assessments this separation is less obvious.

In summary, it is currently unclear which legal frame will be applied in future to a systematic outcome assessment. As long as the data are only used for communication with the patient, the patient-provider contract may provide a sufficient legal base. As soon as other aims are approached, this is probably not sufficient. Since the same data will be used for different purposes, we are confronted with the situation that the same data will fall under different regulations depending on the purpose of the actual use.

- The healthcare practice should have a clear picture about all steps related to collecting, storing, combining, sharing and processing data used as part of the quality management.

- It has to specify for each step the assumed legal basis. Owing to uncertainty about this, the practice should be prepared to adapt its procedures to another legal basis, as soon as there is a further clarification at the national level.

Discussion

Sustainable valid data collection always poses a certain challenge. In research, obstacles are usually overcome with additional resources, dedicated drivers and teams, processes outside the routine and the temporary nature of data collection. The implementation of permanent systematic assessments requires a different approach. Processes have to be implemented in routine daily practice, additional sources are lacking, healthcare providers might be reluctant to embrace change and the duration of data collection is indefinite. Some peculiarities of the Swiss healthcare system imply additional challenges, which have been discussed in this article. In particular, the highly fragmented healthcare system and the lack of established standards for collection of structured data, data storage and data exchange has been emphasised.

There are further challenges in implementing a systematic outcome assessment in healthcare practices, which are not touched in this article, as there are no fundamental differences compared with other countries. This holds in particular for the choice of the instruments, the adaptation to multilingual environments, the analytical approaches to make use of the collected data in the dialogue with the patients or in comparing providers, and the involvement of patients, providers, staff and all other stakeholders in the implementation process.

We have emphasised the tasks each single practice is confronted with, but there are obviously some fields where practices can and need to be supported. First of all, the legal frame has to be clarified to avoid practices running into legal conflicts. This is a task for the authorities, and corresponding negotiations are already on the way. Second, practices need partners on the IT side, and it can only be hoped that more companies are willing to develop and offer corresponding solutions. Third, in many medical fields we have today concurring instruments to measure outcomes (including those mentioned under point 3), which are of equal quality. However, agreeing on some standard instruments and variables to be measured is essential to obtaining data allowing meaningful comparisons. In our opinion it is a task of the scientific medical societies to take the lead in establishing corresponding minimum data sets. Medical societies can also support the establishment of disease-specific registries, which are a natural supplement to a systematic assessment in each practice. Such registries would allow use of the data collected to depict the healthcare situation at the national level and to address a wide range of questions from clinical and epidemiology research.

To successfully implement systematic outcome assessments, the perceived top-down approach chosen by the current amendment of the law on health insurance is problematic, in the sense that healthcare providers and institutions are just forced to contribute. A central task to ensure the sustainability of efforts is therefore to win the support of healthcare providers and healthcare practices by creating a bottom-up movement. The many opportunities for each single practice outlined in this article are hopefully a motivation for many practices to become pro-active and contribute to such a bottom-up a movement dedicated to continuously preserving and improving treatment quality.

Given the current lack of dedicated quality programmes based on PROMs and PREMs, which for example establish a full plan-do-check-act (PDCA) cycle, healthcare providers should be invited to participate in shaping future programmes. The development of such programmes designed for the Swiss healthcare system by its principle actors would empower healthcare providers, offer them a chance to define assessments that are really meaningful for their development and thereby make a substantial and sustainable contribution to the quality development in Switzerland.

AcknowledgementWe are grateful to Rolf Schwendener, COO of the Merian Iselin Klinik, Basel, for comments on the manuscript.

Franziska Saxer, Basel Academy for Quality and Research in Medicine, Basel, Switzerland / University of Basel, Medical Faculty, Basel, Switzerland

Markus Degen, FHNW School of Life Sciences, Institute for Medical Engineering and Medical Informatics, Muttenz, Switzerland

Dominique Brodbeck, FHNW School of Life Sciences, Institute for Medical Engineering and Medical Informatics, Muttenz, Switzerland

References

- Delaunay C. Registries in orthopaedics. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101(1, Suppl):S69–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2014.06.029. PubMed

- Niederländer C, Wahlster P, Kriza C, Kolominsky-Rabas P. Registries of implantable medical devices in Europe. Health Policy. 2013;113(1-2):20–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.08.008. PubMed

- Black N, Burke L, Forrest CB, Ravens Sieberer UH, Ahmed S, Valderas JM, et al. Patient-reported outcomes: pathways to better health, better services, and better societies. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(5):1103–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1168-3. PubMed

- Neuburger J, Hutchings A, van der Meulen J, Black N. Using patient-reported outcomes (PROs) to compare the providers of surgery: does the choice of measure matter? Med Care. 2013;51(6):517–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31828d4cde. PubMed

- Black N, Varaganum M, Hutchings A. Relationship between patient reported experience (PREMs) and patient reported outcomes (PROMs) in elective surgery. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(7):534–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002707. PubMed</jrn>

- Black N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ. 2013;346(jan28 1):f167. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f167. PubMed

- Ministerial Statement OECD. The next generation of health reforms. OECD Health Ministerial Meeting. 2017. Available from: www.oecd.org/health/ministerial/ministerial-statement-2017.pdf [accessed 2020 June 11].

- Calvert M, Kyte D, Price G, Valderas JM, Hjollund NH. Maximising the impact of patient reported outcome assessment for patients and society. BMJ. 2019;364:k5267. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k5267. PubMed

- Gutacker N, Street A. Calls for routine collection of patient-reported outcome measures are getting louder. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2019;24(1):1–2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819618812239. PubMed

- Snyder CF, Aaronson NK, Choucair AK, Elliott TE, Greenhalgh J, Halyard MY, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: a review of the options and considerations. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(8):1305–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-0054-x. PubMed

- International Society for Quality of Life Research. User’s Guide to Implementing Patient-Reported Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice. Version 2: January 2015. Available from: www.isoqol.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/2015UsersGuide-Version2.pdf [accessed 2020 June 10].

- Franklin P, Chenok K, Lavalee D, Love R, Paxton L, Segal C, et al. Framework To Guide The Collection And Use Of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures In The Learning Healthcare System. EGEMS (Wash DC). 2017;5(1):17. doi:https://doi.org/10.5334/egems.227. PubMed

- van der Wees PJ, Verkerk EW, Verbiest MEA, Zuidgeest M, Bakker C, Braspenning J, et al. Development of a framework with tools to support the selection and implementation of patient-reported outcome measures. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2019;3(1):75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-019-0171-9. PubMed

- Elixhauser A, Pancholi M, Clancy CM. Using the AHRQ quality indicators to improve health care quality. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31(9):533–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(05)31069-5. PubMed

- Farquhar M. AHRQ Quality Indicators. In: Hughes RG, editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008.

- Burwell SM. Setting value-based payment goals--HHS efforts to improve U.S. health care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(10):897–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1500445. PubMed

- Timpka T, Nyce JM, Amer-Wåhlin I. Value-Based Reimbursement in Collectively Financed Healthcare Requires Monitoring of Socioeconomic Patient Data to Maintain Equality in Service Provision. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(12):2240–3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4661-x. PubMed

- Erickson SM, Outland B, Joy S, Rockwern B, Serchen J, Mire RD, et al.; Medical Practice and Quality Committee of the American College of Physicians. Envisioning a Better U.S. Health Care System for All: Health Care Delivery and Payment System Reforms. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(2, Suppl):S33–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-2407. PubMed

- Pouwer F, Snoek FJ, van der Ploeg HM, Adèr HJ, Heine RJ. Monitoring of psychological well-being in outpatients with diabetes: effects on mood, HbA(1c), and the patient’s evaluation of the quality of diabetes care: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(11):1929–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.24.11.1929. PubMed

- Field J, Holmes MM, Newell D. PROMs data: can it be used to make decisions for individual patients? A narrative review. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2019;10:233–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/PROM.S156291. PubMed

- Sørensen NL, Hammeken LH, Thomsen JL, Ehlers LH. Implementing patient-reported outcomes in clinical decision-making within knee and hip osteoarthritis: an explorative review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):230. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-019-2620-2. PubMed

- Skovlund SE, Lichtenberg TH, Hessler D, Ejskjaer N. Can the Routine Use of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Improve the Delivery of Person-Centered Diabetes Care? A Review of Recent Developments and a Case Study. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19(9):84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-019-1190-x. PubMed

- Greenhalgh J, Dalkin S, Gibbons E, Wright J, Valderas JM, Meads D, et al. How do aggregated patient-reported outcome measures data stimulate health care improvement? A realist synthesis. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2018;23(1):57–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819617740925. PubMed

- Zhang R, Burgess ER, Reddy MC, Rothrock NE, Bhatt S, Rasmussen LV, et al. Provider perspectives on the integration of patient-reported outcomes in an electronic health record. JAMIA Open. 2019;2(1):73–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jamiaopen/ooz001. PubMed

- Swiss Ethics Committees on research involving humans: Quality assurance, or research subject to approval? Version 1.0 of February 1st, 2020. Available from: swissethics.ch/assets/pos_papiere_leitfaden/191223_abgrenzung-qualitatssicherung-von-forschung_finalisierte-version_de_en.pdf [accessed 2020 June 10].